Air quality falls as fires intensify

Dangerous fine particulates increase

By Abhinanda Bhattacharyya and Stephanie Zhu

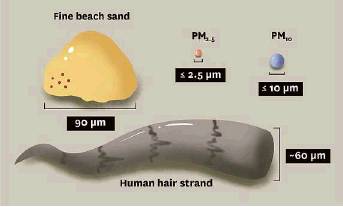

Fine particles called particulate matter 2.5 are tiny but incredibly dangerous.

Many scientists now view these inhalable particles with a diameter of 2.5 microns or less as the most damaging source of pollution for Bay Area residents, and for many other communities across the globe. Particulate matter consists of a combination of liquid droplets and small solid particles.

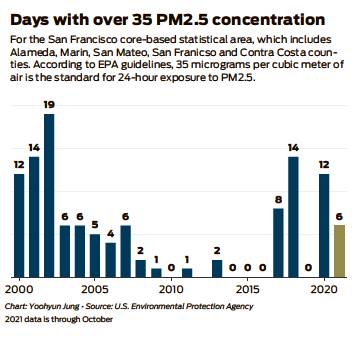

PM2.5 levels in the Bay Area were on a downward trend between the early 2000s and the mid 2010s. Then, as wildfires intensified across the state, they began to climb again. Last year, the region blew past the record for Spare the Air alerts, recording a total of 52 by December, driven largely by high PM2.5 concentrations from wildfires. The daily average PM2.5 concentration in the Bay Area from 2018 to 2020 was more than 15% higher than it was between 2015 and 2017.

Not only is the Bay Area seeing more PM2.5, but more of a particularly bad kind. PM2.5 that originates from combustion sources like wildfires and emissions from cars is generally more toxic to human health than non-combustion source particles, like those triggered by dust storms, according to John Balmes, a professor of medicine at UCSF and environmental health sciences at UC Berkeley.

Our bodies don’t like any type of pollution, but they especially don’t like PM2.5 because those particles are so tiny that when we inhale them, they make their way deep into our lungs. Once they get there, the chemicals on the surface injure the cells lining the lower airways and air sacs. Our bodies can react by mounting an inflammatory response, a defense mechanism triggered when we get injured, or to protect us against harmful agents, like bacteria. That inflammatory response is the same process that turns a coronavirus infection into COVID-19 and sends patients to the hospital. The amount of inflammation depends on the amount of PM2.5 inhaled.

Particulate pollution can be driven by a variety of sources. In the Bay Area, directly emitted particulate matter from sources like oil refineries, residential wood burning and exhaust emissions, account for about 45% of the total fine particulate matter we inhale, according to the latest analysis from the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. The remaining 55% comes from particles formed in the atmosphere from gaseous pollutants. The analysis was based on data from 2016, the latest date the agency had good data.

Of the directly emitted particulate matter in 2016, about 12% came from residential wood burning, 10% from five oil refineries in the Bay Area, 8% from restaurants and 6% from off-road sources like trains and aircraft, according to the district. Since 2016, wildfire smoke has become a far more significant contributor to particulate matter pollution in the Bay Area.

Increased and prolonged exposure to PM2.5 can have serious health impacts. It can exacerbate several conditions, including diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart disease, according to Balmes. Elderly people, pregnant women, who could potentially face adverse birth outcomes, and children, still developing their lungs and other organs, are especially vulnerable. Last year, Stanford researchers estimated that exposure to high concentrations of PM2.5 from wildfire smoke in California may have contributed to up to 3,000 premature deaths.

Exposure to high levels of PM2.5 could also make young, healthy people more vulnerable to lower respiratory tract infections. Exercising outside when PM2.5 levels are high also increases the effective dose of the pollutant because people tend to breathe through their mouth rather than their nose while exercising, when their muscles need more oxygen. In doing that, they bypass the scrubbing mechanism of the nose, while inhaling more air per minute than they typically would resting.

So far this year, the Bay Area has been breathing easier because of a combination of weather and wind conditions, and wildfires burning further away. But, the year isn’t over, and the region typically sees the highest concentrations of PM2.5 in November and December, according to Michael Flagg, the district’s principal air quality specialist. That’s because of a combination of meteorological conditions during that time of the year and emissions from residential wood burning.

Compared to many large cities around the world, where long-term exposure to high levels of PM2.5 has likely lowered life expectancy, air quality in the Bay Area is still relatively good overall. But, as wildfires rage longer and with more intensity, and we see longer periods of sustained exposure to PM2.5, researchers don’t know what the longer term public health impacts will be. Because the recent years of record wildfires are a new phenomenon, that data just does not exist yet.

Abhinanda Bhattacharyya and Stephanie Zhu are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: abhinanda.bhattacharyya@sfchronicle.com, stephanie.zhu@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @abhinanda_b, @stephzhu_