Could the Bay Area lose BART?

What to know about the transit system’s ‘fiscal cliff’

By Ricardo Cano

When it came to financial independence, none of the largest transit agencies in the country did it better than BART.

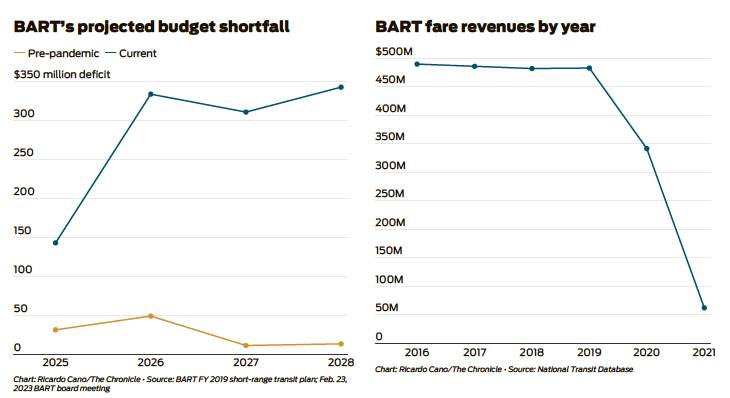

Fares have been the bedrock of BART’s financial model ever since its first trains zipped across the Bay Area 50 years ago. Next to Caltrain, no other U.S. rail agency in 2019 had a higher farebox recovery ratio — the percentage of operating expenses covered by fares — than BART.

Even in tough economic times, the system stayed afloat — and expanded — as long as commuters packed into BART trains, making it a standard-bearer for financial self-sustainability in the transit world.

Now, the business model that had been both an outlier and a point of pride for the Bay Area’s regional rail system could become its undoing.

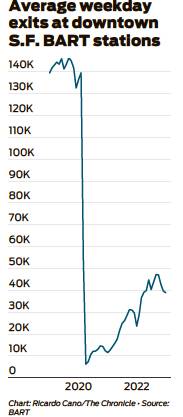

BART is the connective tissue for the Bay Area’s public-transit network, but has had one of the nation’s most anemic ridership recoveries, down roughly 60% from 2019 figures, since telework took hold across the region.

Its pre-COVID ridership is unlikely to return in the next decade, making BART’s future especially perilous as transit agencies across the Bay Area and the nation project massive budget shortfalls.

In its worst-case scenario, BART would impose mass layoffs, close on weekends, shutter two of its five lines and nine of its 50 stations and run trains as infrequently as once per hour. Those deep cuts, agency officials say, could lead to the demise of BART.

A Bay Area without BART, however unimaginable, would further fragment public transit, worsen traffic congestion on highways and bridges, and erode the natural flow of a region so profoundly shaped by the rail system.

Here’s what you need to know:

When will BART reach its ‘fiscal cliff’?

After transit ridership fell to all-time lows in April 2020 during the depths of the pandemic, the federal government stepped in with a temporary lifeline. It provided unprecedented subsidies to the nation’s transit agencies, helping them avert doomsday-level cuts in service.

Of the $4.5 billion that went to the Bay Area’s 27 transit agencies, BART received about $1.6 billion, which it used to make up for a dramatic loss in fare revenue and restore service cuts made in 2020.

The transit agency will run out of federal money in January 2025 — six months earlier than previously projected.

Similar transit fiscal cliffs are playing out across the country. In D.C., the transit agency is forecasting annual deficits of up to $500 million. Chicago’s transit system projects it will be $700 million in the red by 2026. The agency that operates New York’s famed subway system faces a $3 billion budget gap by 2025.

Each of these agencies are pressing their state legislatures for subsidies and considering fare increases.

The nation’s transit systems remain in a financial purgatory, said Garrett Shrode, an policy analyst at the D.C.-based Eno Center for Transportation, and no large U.S. transit agency has yet secured funding to avoid their looming deficits.

“Politicians pass around the phrase all the time, ‘it’s too big to fail’ because money has to come from somewhere,” Shrode said. “But no one wants to fork over the money to plug these holes in order to prevent cutting service.”

How steep is the fiscal cliff?

Even before the pandemic, officials projected BART would be in the red in the coming decade, incurring small annual operating deficits.

Those projections pale in comparison to the agency’s latest forecast: a $143 million budget deficit by 2025.

By the following fiscal year, the funding gap will grow to $300 million annually — about 30% of BART’s current operating budget.

Other Bay Area transit operators, such as Muni, Caltrain and Golden Gate Transit, are projecting their own large deficits in the coming years. Agencies that don’t rely on fares, meanwhile, aren’t facing a fiscal cliff.

BART’s deficit, however, is expected to make up nearly 40% of the region’s $800 million overall transit shortfall by 2028, according to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission.

How did BART spend its federal pandemic aid?

BART used its federal pandemic relief to keep trains running every half hour in 2020 on weekdays. It restored weekday service to 15-minute frequencies in August 2021, when ridership was at 22% of pre-COVID levels. Last year, the agency increased weekend service above what it was in 2019.

Some board directors at the time argued that the agency should have held off on restoring service to make the federal funds last longer. But BART officials said it was important that BART put out frequent service for riders who depend on the system.

Ridership, they say, would have been lower than what it is today had the agency not boosted service.

Can BART ridership recover as remote work continues?

These days, more than 160,000 people per day ride BART during the middle of the week, now the busiest time to ride the system.

Still, that ridership amounts to about 40% of the typical weekday in 2019.

The pandemic highlighted BART’s high dependence on office commuters bound for downtown San Francisco. Before the pandemic, the four stations on Market Street accounted for more than one-third of weekday exits across the 50-station system. As of January, with downtown still hosting a fraction of its previous in-office workforce, those downtown stations — Embarcadero, Montgomery, Powell and Civic Center — saw 28% of their pre-pandemic exits, according to BART data.

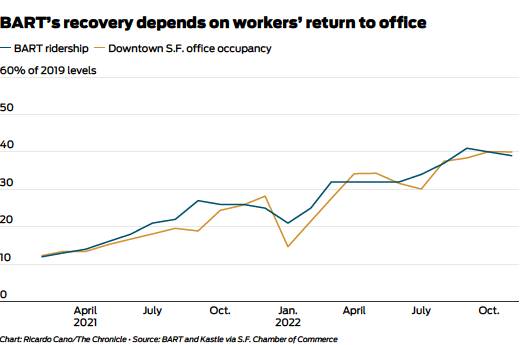

BART’s overall ridership recovery during the pandemic has mirrored downtown’s office occupancy levels.

In a recent conversation with downtown employers, BART Chief Communications Officer Alicia Trost was blunt about how much of a threat telework poses to the rail system.

“Our service is completely tied to your office occupancy, more than any other agency in the Bay Area,” Trost said at a recent Bay Area Council panel. “I’m not kidding, we will not survive if you don’t bring your employees back” to offices.

What is BART doing to bring back riders?

The agency has touted several forthcoming changes that officials say will improve the riding experience during BART’s push to bring back riders. BART will be doubling the frequency of deep cleaning on stations and trains and vowing to improve from recent declines in service. Starting March 20, more police officers will patrol trains and station platforms.

The BART board is also expected to award a contract at its March 23 meeting to replace all of the system’s fare gates to deter fare cheats.

The menu of changes are in response to the agency’s most recent customer satisfaction survey showing a 67% approval rating from riders. The rating is higher than BART’s all-time low of 56% in 2018, but found low satisfaction scores for the lack of police presence on trains and stations, fare evasion enforcement and the proliferation of homelessness on the system.

Fare cheats cost BART an estimated $25 million a year in lost revenue before the pandemic. Hardened gates, officials say, would curtail most fare evasion attempts and could go a long way toward increasing paying riders’ sense of personal safety on BART.

What will BART’s ridership be in the coming years?

Earlier in the pandemic, BART officials projected ridership would rebound to 59% of pre-pandemic levels by 2025, with a 70% recovery by the end of the decade.

Updated projections acknowledge that those projections were too optimistic, and now forecast ridership at 49% of 2019 levels by 2025. In 2019, for reference, BART trains carried 420,000 riders on an average weekday, with crushing loads of riders during peak morning and afternoon commute hours.

BART has also been among the outliers when it comes to recovering ridership. San Diego (73% of pre-COVID levels), New York City and Los Angeles (both at around 68%), Boston (57%) and San Francisco’s Muni (55%) have recovered greater shares of their ridership. Many of them, however, face similar challenges as BART and, to date, no large U.S. transit agency has fully recovered their pre-pandemic ridership.

Will BART raise fares to plug its budget gaps?

The agency’s board is likely to support raising fares 11% over two years starting in 2024 — inflationary increases that were paused during the pandemic.

But if BART were to solely rely on fare hikes to plug its budget deficit, it would have to “more than double” its current fares, said BART Financial Planning Director Michael Eiseman.

Put another way: Riders traveling from Dublin/Pleasanton Station to Powell Station in downtown San Francisco would have to pay nearly $14 for a one-way fare compared to the current fare of $6.85. Fares at those prices, Eiseman said, would price out many riders from taking BART, and create a self-fulfilling prophecy referred to as a transit death spiral — a cycle where declining ridership leads to service cuts, and vice versa.

BART officials are considering other cost-cutting measure beyond fare increases to bridge the funding gap.

At recent board meetings, some of the agency’s board directors suggested officials eliminate positions at BART deemed inefficient. Others have supported halting converting parking lots into housing if those projects don’t bring a clear profit for BART. Several suggested BART should divert any discretionary funds earmarked for planning toward long-term expansion projects, such as a second Trans-bay Tube, to address its fiscal cliff.

“I recognize that our priorities are existential right now,” BART board President Janice Li said. “And if we cannot survive through our current crisis, there will not be a future where we can someday ride a second transbay rail crossing or to downtown San Jose.”

As of now, those proposals remain merely suggestions, though the pandemic’s aftershocks have already impacted planning for large-scale capital projects that were once thought necessary, such as a second tube for BART.

Is there a long-term solution for BART?

Not at the moment.

But BART leaders say achieving financial stability for the agency means making an unprecedented change to how the rail system gets funded.

“Our funding model is outdated and is no longer the best approach for paying for an essential service that the entire region depends on, one way or another,” BART General Manager Bob Powers said. “Instead of relying mostly on fares, we must invert our funding formula to rely more heavily on subsidies and a sustainable source of revenue that recognizes ridership recovery will take years.”

A subsidy, Powers said, would have to come from either the state or local taxpayers via a ballot measure that would allow BART to wean off its high reliance on fares.

Subsidies would put BART more in line with how other large U.S. transit systems get funded. About 53% of D.C. Metro’s $2.3 billion operating budget, for example, comes from local and state subsidies. Roughly 13%, or $301 million, comes from fares.

BART is at the center of a lobbying effort by the state’s transit agencies to secure “gap funding” in the state budget, hoping it will buy agencies more time to ask Bay Area voters for a long-term subsidy in 2026.

Transit agencies will make a specific ask to Gov. Gavin Newsom and state lawmakers at the end of March. Though with California projecting its own deficit, the effort faces tough headwinds.

BART, for its part, will conduct polling this spring as part of its push for a local ballot measure. Officials have not discussed what kind of tax that measure would be, and Bay Area transit agencies could band together to ask voters’ approval on a mega measure in 2026.

Where do state lawmakers stand on a transit subsidy?

BART directors acknowledge that legislators, so far, have been lukewarm to the idea of including transit operations funding at a time when the state faces a $22 billion deficit.

Newsom’s January budget included $2 billion in cuts to transit projects with no subsidy, highlighting the challenges of securing a state bailout.

San Francisco state Sen. Scott Wiener and other lawmakers are championing an effort for a transit subsidy. They say BART and other transit agencies are too vital to the region and state to let them financially flounder on their own. Some legislators were empathetic to transit agencies at a recent hearing of a committee specifically created to address their fiscal cliffs.

One Bay Area lawmaker, Democratic Sen. Steve Glazer of Orinda, wants to tie a subsidy to greater financial oversight of BART. As BART officials lobby the state for a subsidy, they’re also in the middle of a years-long battle over the authority of BART’s Office of the Inspector General — which Glazer, who pushed to create the office in 2018, has introduced legislation to strengthen.

And while BART and other Bay Area agencies would benefit greatly from a state bailout, transit advocates have acknowledged that securing votes for a bailout rests on support from Los Angeles-area lawmakers. Agencies in Southern California are also facing deficits, though generally aren’t fare-dependent and are further ahead in recovering ridership.

Is there hope for BART’s future?

There are two key reasons things appear bleak for BART right now: There’s no guarantee it and other California transit agencies will secure a state subsidy, and BART officials have little time before they will have to consider painful service cuts.

In a best-case scenario for BART, California lawmakers pass a bailout this legislative session, with money flowing as early as this fall.

But if the agency does not secure a subsidy from the state or local taxpayers by spring 2024, board directors will likely have to consider making steep cuts in service in the budget for that upcoming budget cycle, when BART’s fiscal cliff is realized.

Leaders of the Bay Area’s transit agencies appear adamant in banding together to ask voters for a tax measure, which would require two-thirds approval, in 2026 in part to avoid a crowded ballot in 2024. Viewed as the long-term fix, a regional subsidy under this timeline would not arrive in time for the agency to avert its $143 million deficit in 2025 — assuming voters would pass it.

Officials at BART have not publicly discussed other options beyond the state subsidy lobbying push and a regional ballot measure that remains undefined.

“We’ve built our budget around peak worker riders, and when they went away, it sort of broke our back and broke the budget,” Board Director Mark Foley said in late January. “I am concerned in putting (all) our eggs in the tax measure basket. What if that fails, like so many other ballot measures fail because people don't want to be taxed anymore? What if that happens? What is Plan B?”

Reach Ricardo Cano: ricardo.cano@sfchronicle.com

Twitter: @ByRicardoCano