Development triumphs over urban farming

Tussle over future of historic greenhouse site in S.F.’s Portola

By J.K. Dineen

In the end, housing trumped urban farming in San Francisco’s Portola district.

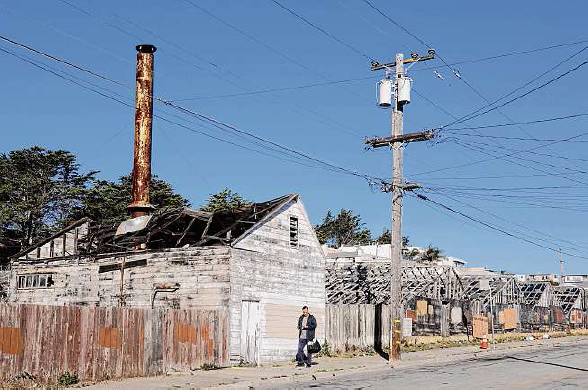

A quixotic neighborhood dream of building an urban farm and agricultural education center on the site of abandoned greenhouses in the heart of the Portola has fizzled out after the property owner couldn’t agree with community organizers on a price for the 2.2-acre site. Instead, the property owner, Group I, plans to go ahead with an approved 62-unit development on the parcel at 770 Woolsey St.

Urban farm backers envisioned a place where schoolkids could learn about sustainable farming, neighbors could buy produce and the isolated blue-collar neighborhood — which is cut off from much of the city by Interstate 280 and Highway 101 — could gather at a town square.

But the developer wants to move ahead with the long-stalled project as San Francisco confronts a state mandate to get 82,000 homes built by 2031, underscoring the difficult calculus for neighborhoods that want both community space and housing.

Dave Gabriner, a Berkeley firefighter who co-founded the Greenhouse Project, said his organization raised $15 million to buy the site, the top end of the range the two sides had agreed on in an option deal two years ago that’ll expire at the end of October.

“This project has been incredibly important to the Portola, and it’s been inspiring how profound the support and excitement has been throughout the city and the state,” Gabriner said. “It’s unbelievably disappointing that we couldn’t work out a deal.”

Gabriner said the $15 million — twice what Group I paid for the site in 2017 — came from foundations and individuals as well as the California Department of Natural Resources, which granted the group $6 million.

While there are still technically a few days left to make a deal, if that doesn’t happen, the developer is committed to a 62-unit town house development with solar rooftops and ample green space, said Leigh Chang and Mark Shkolnikov, principals with Group I. The plan calls for carving out 17,200 square feet of community space on the northeast corner of the property where two replicas of the historic greenhouses will be built and the boiler house will be restored.

Chang said she’s optimistic that the project can be financed despite the fact that rising interest rates and inflation have stalled many housing projects. The project, which will have mostly three- and four-bedroom units, will include 20% of units at below market rates.

“We are still excited about the residential project,” Chang said. “We have had conversations with several lenders.”

Supervisor Hillary Ronen, who represents the neighborhood, called the broken deal “heartbreaking.” She said the proponents of the Greenhouse “were reasonable and upfront in negotiations” and surprised everyone by raising so much money.

“This is not a NIMBY group in any way, shape or form,” she said. “This was a once-in-a-lifetime special plot of land where there is a business plan in space to create a learning center and functioning urban farm that would be a demonstration project for the entire world.”

Before World War II, there were 19 blocks of greenhouses in the Porto-la, mostly operated by Italian and Maltese immigrants. Over the past decade, the Greenhouse Project has delved into that history, and the neighborhood has rallied around reclaiming the mantle of the city’s “garden district.” The group took over the Caltrans easement along the 101, planting gardens and building seating in what had been garbage-strewn dead ends off San Bruno Avenue, the neighborhood’s commercial strip.

Gabriner emphasized that the Greenhouse group has never been anti-housing. They wrote a letter of support for the project when it was up for approval at the Planning Commission last year. And they declined to initiate the historic landmarking of the site, which would have precluded a residential development there.

“There was no aspect of the project that had to do with preventing housing from being built,” he said. “It was about a neighborhood that over a decade of work came up with a vision for what it wanted to do with the site.”

Project Greenhouse’s Caitlyn Galloway, who spent years operating Little City Gardens near the site, said, “Investing in community-focused, culturally relevant local food economies is a responsibility we have to future generations.” She had hoped to grow “cool-season produce” as well as tender greens, herbs, flowers and seedlings that could be sold to backyard gardeners.

Yensing Sihapanya, executive director of Family Connections Centers, which runs 30 programs for families in the Portola and Excelsior neighborhoods, said the greenhouse project not going forward would be a blow to families, many of whom immigrated from China.

“Having quality accessible outdoor space is something we learned to appreciate during COVID,” she said. “So many of our families find the tiniest little space to grow on and bring in and trade each other for their lemons and produce. Having something like the greenhouse project would be incredible.”

Corey Smith, executive director of the Housing Action Coalition, said that he sympathizes with the Portola community members who fought so hard to create something unique. At the same time, he said, 2.2 acres zoned for housing in a family-oriented residential neighborhood is a rarity in San Francisco because for decades zoning banned multi-family development in two-thirds of the city.

If more of the city were to be opened up for denser residential development, it would be easier to justify setting aside something like 770 Woolsey for another purpose.

“Reasonable people understand that there are a whole bunch of things you need to make a city work,” he said.

J.K. Dineen is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: jdineen@sfchronicle.com Twitter:

@sfjkdineen