Wine Country reels from beetle attacks

Die-off of trees forces emergency declaration, adds to fire risk

By Kate Galbraith

The loathed bark beetle has munched its way into the Wine Country hills.

The beetle, which recently caused a massive die-off of conifers in the Sierra Nevada, is doing the same thing in Napa County and nearby areas — stirring grave concerns about fire risk and ecological turmoil.

So worried is Napa County about its dying trees that officials recently declared an emergency.

Lake County made a similar proclamation in May, and other counties — such as Mendocino and Sonoma — may also want to consider emergency declarations, according to Michael Jones, a forestry adviser with UC Cooperative Extension.

“Fire and insects do not observe boundaries,” Jones said.

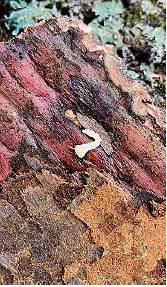

Many trees have been killed by drought and wildfire. But those that escaped are significantly weakened — making them vulnerable to the bark beetle, which preys on conifers like ponderosa pines and Douglas firs.

The problem is so significant that even some oak trees are being affected in Napa County, Jones said.

“That’s how you know things are kind of really bad, when you see oaks succumb to drought stress,” he said.

Jake Ruygt, a botanist who has been studying vegetation in Napa County since 1976, said the conifer impacts became obvious a few years ago. He has been studying vegetation in the region for more than 40 years and has never seen a bark beetle outbreak this bad.

“It’s pretty scary,” he said. The east side of the Napa Valley is particularly affected, he said, and “around Angwin, I’m seeing 15-25% die-off of conifers.”

What’s happening now are “mass attacks,” said Jones. That’s when the beetle population is so dense that they attack even healthy trees.

“They’re out of the fire footprints, they’re spreading across the landscape” in pockets, Jones said, adding that it could get worse next year, if a wet winter fails to materialize — though conversely, a winter of normal rainfall would likely help.

Redwood trees are conifers, but the beetles so far have not attacked large, natural stands of them. However, they have attacked ornamental redwoods that are planted away from their normal habitat, Jones said.

“I don’t think folks understand how threatened they are by wildfire because of the diseased and/or dying trees,” county Supervisor Diane Dillon said when approving the emergency resolution.

The Sierra Nevada has borne the brunt of bark beetle attacks. The beetle, in combination with last decade’s severe drought, killed about 62 million California trees in 2016 alone, mostly in the central and southern Sierra, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

“We’re kind of experiencing our own mini version of that right now,” Jones said, adding that the beetles have recently returned to the northern and central Sierra.

Closer to the Bay Area, the worst outbreak has been in Lake County, Jones said, followed by Napa County. Landowners in Mendocino and Sonoma counties should also be concerned, in addition to those in parts of Humboldt County.

“What may appear on the surface as a perfectly healthy tree, may well be stressed out,” said Cal Fire forester Peter Leuzinger.

Angwin resident Kellie Anderson said she could see 50% tree mortality from her yard. There are “monstrous dead conifers” throughout the area, she said.

Besides Douglas firs and ponderosa pines, she said, gray pines have been impacted. “When you see those trees that you consider to be indestructible ... when you see them collapsing, you know you’re in trouble,” she said.

In parts of Napa County, “You can stand there and go wow — they told me climate change would affect my grandchildren. Wow, it’s affecting me.”

Emergency orders unlock only limited local money, but they are also a call for help to the deeper-pocketed state. If enough counties band together, it can get the state’s notice, and a regional effort to address the problem could be created, Jones said.

Unfortunately, there’s not a quick fix. The beetle is going to munch whatever stressed trees are available, and there is no stopping it. But money could help remove dying trees that pose a hazard from crucial areas like parks and campsites.

Better forest stewardship can also make a difference over the long term. And at Las Posadas State Forest in Angwin, the outbreak has been pronounced, according to Leuzinger, who manages the 800-acre experimental forest for Cal Fire. But Cal Fire has tried to be “a little more preemptive and aggressive with management” of the outbreak, he said. It has removed some trees affected by the bark beetle. That reduces the tree density — an important part of stewardship, many forest experts say — and also gets rid of beetle-infested lumber, which can be used to create wood products.

Ultimately, the beetle is native to California, and its proliferation is more a symptom of a broader problem — which includes drought, climate change and more than a century of fire suppression — than the root cause.

“The best way to manage for bark beetles,” Jones said, “is to create healthy, vigorous forest stands.”

Kate Galbraith is the San Francisco Chronicle’s climate editor. Email: kgalbraith@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kategalbraith