Attack on author reminder of 1989 Berkeley blasts

By Rachel Swan

Salman Rushdie, the author stabbed multiple times Friday as he prepared to deliver a talk in New York, had once sparked a political inferno in Berkeley — when his critics are believed to have bombed two bookstores, testing the city’s faith in free speech.

The events of February 1989 still loom heavily for Andy Ross, the former owner of Cody’s Books on Telegraph Avenue. Rushdie’s novel, “The Satanic Verses,” had come out a few months earlier in the United Kingdom, earning plaudits from the literary world but angering people with its references to the Quran, which many considered blasphemous.

“We knew it was kind of dangerous,” Ross told The Chronicle on Saturday, recalling protests that ignited all over the world, eventually hitting his store after the book shipped.

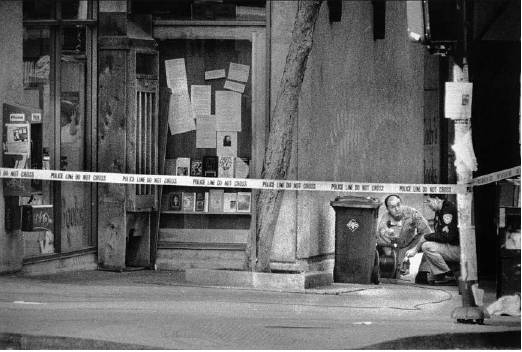

Undeterred, Ross opted to keep “The Satanic Verses” in stock, hoping to sidestep controversy if he left it out of the front window display. Then one night he got a call from police, saying someone had thrown a firebomb into the store. While nobody left a threat or came forward later, Ross and investigators saw the bombings as retaliation for his decision to sell the book.

No one was hurt, though the bomb charred a bookshelf and the firefighters who responded left significant damage, Ross said. When he and his staff arrived to clean up the next day, they found an undetonated pipe bomb in the poetry section, and had to call a bomb squad to blow it up.

“They said it would have killed everyone in the store,” Ross recalled, his voice shaking. “And this is the part where I get really choked up. We all went to the store afterwards, and I told my staff, ‘I don’t know what you want to do. This book is dangerous.’ So we took a vote. And we voted unanimously to keep carrying the book.”

He paused a beat.

“And that was one of the highlights of my career.”

Still, Ross acknowledged he might remember the vote as foolhardy, rather than principled and heroic, had people died in a subsequent bomb attack. Tension was stewing over Rushdie’s novel, even in progressive, First Amendment-loving Berkeley. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of Iran after its 1979 revolution, issued a fatwa in February 1989 ordering Muslims to kill Rushdie.

The death sentence came down just as “The Satanic Verses” arrived in Berkeley bookstores, apparently provoking outrage.

On the night Cody’s was attacked, someone also hurled a brick and a Molotov cocktail into a nearby Waldenbooks store. In the weeks that followed, people began pointing fingers at the Muslim community, ratcheting up hostility even though the perpetrators of the bombings were never identified, their motivations were never confirmed, and such violence would be the work of offshoot extremists.

To Robert Gammon, the former manager of the Waldenbooks branch, the impetus for the bombings was “pretty clear.” Nonetheless, he refused to stop selling Rushdie’s novel.

“It was a freedom of speech issue,” Gammon, now the communications director for state Sen. Nancy Skinner, said Saturday. “We’re a bookstore — we’re not going to cower in fear or hide the book in the back, or something. Even after we got firebombed, we got more copies in stock. And they sold pretty well.”

At some point, members of Islamic student associations at UC Berkeley came to Cody’s and offered their condolences, making clear they did not support violence, Ross said.

Years later, Rushdie made a surprise appearance at Cody’s. He was still in hiding, so employees were notified only 15 minutes before he came in, Ross said. They gave him a tour and showed him a crack in the drywall above the information desk, left from the 1989 bombings. Someone had scrawled “Salman Rushdie memorial hole” near the indentation.

Ross remembers the author’s droll reaction. “Well,” the author said, “some people get statues, and others get a hole.”

Cody’s closed its flagship store on Telegraph Avenue in 2006, and later shuttered branches in North Berkeley and San Francisco. Ross now works as a literary agent.

Police arrested Hadi Matar, 24, of New Jersey on Friday after Rushdie was stabbed 10 times as he prepared to deliver a talk at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York. In a court arraignment Saturday, Matar pleaded not guilty to what prosecutors say was a premeditated attack.

Rushdie, 75, suffered a damaged liver and severed nerves in an arm and an eye, news outlets reported. He was taken off a ventilator and is able to talk, but he remains hospitalized with serious injuries and may lose the eye, reports said.

Chronicle news services contributed to this report.

Rachel Swan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: rswan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @rachelswan