Housing crisis shifts People’s Park dynamic

By Rachel Swan and Michael Cabanatuan

To any longtime resident of Berkeley, the scene at People’s Park Thursday morning might seem uncannily familiar: felled tree branches piled at the edge of the grass, a torn-down steel fence, a protest banner hanging between two damaged bulldozers.

It wasn’t the first time the 2.8-acre site east of Telegraph Avenue had come to resemble a war zone, amid an ongoing standoff between UC Berkeley — which owns the park and seeks to quilt it with desperately needed housing for students and formerly homeless people — and demonstrators who claim People’s Park as a gathering space and sacred symbol of Berkeley counterculture.

Debates over the park’s fate have stewed for more than 50 years, but it wasn’t until the construction crews arrived Wednesday that a dramatic change began taking shape.

In a frantic attempt to stop it, protesters ripped down the security fence around the park’s perimeter and smashed windows and mechanical components on several bulldozers and earthmovers. It was unclear Thursday when building might resume.

Dan Mogulof, a spokesperson for the university, said time was running out to restart the $312 million project, which would house more than 1,100 students and 125 formerly homeless people and is part of a larger push by UC Berkeley to help address a chronic dearth of student housing.

“If we want to have this building available for students to move in during the fall of 2024, we have a pressing need to get started as quickly as possible,” he said. “Our commitment to this project is unwavering.”

Advocates seeking to preserve the park as an open space sued to block the development from being built. Last week, an Alameda County Superior Court judge issued a tentative ruling that the project could go forward. Crews broke ground in the early hours of Wednesday morning, quickly attracting the attention of dozens of protesters.

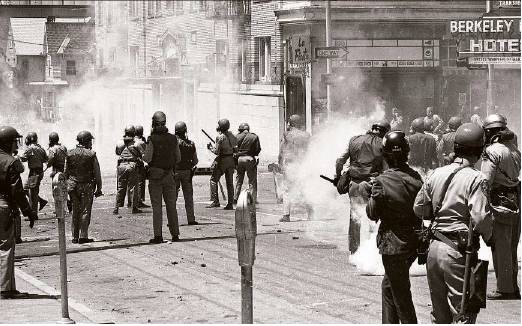

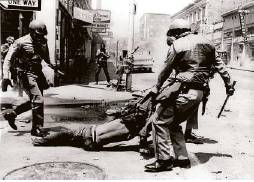

Similar confrontations have occurred throughout the park’s history, which began in the late 1960s when UC Berkeley took possession of the land and cleared it of homes, sparking a huge protest that culminated with “Bloody Thursday” in 1969, when sheriff’s deputies shot and killed a bystander.

Battles broke out over the university’s plan to build a soccer field in 1971, its effort to pave an area for vehicle parking in 1979, its installation of volleyball courts in 1991, and maintenance work in 2011 that required removal of plants at the park’s western end.

“It’s a political and cultural institution,” said Harvey Smith, a Berkeley historian and president of the People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group, one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit. A judge sided with the university, but the plaintiffs appealed Thursday.

“This is beyond a community struggle with the university,” Smith said. “This park is a national historic site. From a historic and cultural perspective, we need it. From an environmental and recreational perspective, we need it.”

But the backdrop of UC Berkeley’s dire need to house its students and the Bay Area’s broader housing crisis may be shifting perceptions about the struggle. Even Berkeley City Council members who often butt heads over land use have aligned in supporting this project.

“We respect the important history and the meaning of People’s Park,” Berkeley Council Member Sophie Hahn told The Chronicle. “But it’s our goal to have people housed.”

Mayor Jesse Arreguín said Berkeley’s elected officials are unified on the issue. The city committed $14 million to build one component of the project, permanent supportive housing. They hope to alleviate the signs of obvious despair that Berkeley residents see welling up in the park, including crime, encampments and drug use.

Longtime labor movement lawyer Tom Dalzell, who wrote a book on People’s Park, said the university is “really skillfully manipulating public opinion,” by allowing the park to get overrun with encampments. This form of benign neglect ultimately made the space intolerable, Dalzell said, so “there’s not much, if any, support for the status quo.”

Mogulof, the UC Berkeley spokesperson, countered that the university spent hundreds of thousands of dollars annually to maintain restrooms, keep water running and provide security at People’s Park — expenses that strained an institution whose primary mission was academics. The notion the UC Berkeley ignored the space “presupposes that the university was in effect resigned to abandoning an incredible piece of real estate” that could serve the needs of its students, Mogulof said.

Yet as conditions in People’s Park declined, a larger demographic and cultural evolution was reshaping Berkeley, making it considerable less radical than in the 1960s, Dalzell said. When the new volleyball courts sparked a riot in 1991, public sympathy for protesters had already dwindled significantly since the Summer of Love era. It kept diminishing as the years went by. Telegraph Avenue became more gentrified, and progressives on the City Council started siding with pro-housing advocates more consistently than in previous decades.

Polls paid for by UC Berkeley in May showed that 57% of student respondents favored a development project at People’s Park. Once they received information on the project’s main elements — student housing, supportive housing, markers to commemorate the park’s past, a daytime drop center for unhoused people and preservation of green space — support rose to 62%.

“It’s more than a shift, it’s a sea change,” Mogulof said, citing several factors that steered community sentiment in favor of housing. Soaring real estate prices have forced many students to couch surf or live from one rent payment to another, and roughly a quarter don’t even live in Berkeley, he said. These fluctuations in the housing market coincided with a change in leadership. Chancellor Carol Christ and Mayor Arreguín became bullish on the housing crisis, saying the city and university had an obligation to care for students and the unhoused.

“When I started working on campus 19 years ago and asked about People’s Park, I was told it was a third rail of Berkeley politics,” Moguluf said. “Now you can see the change.”

Nonetheless, passions among a small group of die-hard park preservationists are no less heated. Seven people were arrested Wednesday after protesters knocked down fences and stood in front of construction vehicles. Charges included battery of a police officer, trespassing, resisting and obstructing or delaying an officer. Construction workers had to be evacuated for safety before they could pick up the tree branches piled on the ground.

On Thursday, protesters reassembled pieces of the fence to fortify their encampment. Some sat in the sun or in the shade of a few remaining trees, talking or reading books. Signs of resistance were everywhere, from the shredded cables and spark plugs ripped out of earthmoving machines to the phrase “No war but class war” spray-painted on the scoop of a bulldozer.

Smith said the park activists agree with university on at least one point: They all support student housing. But the activists want it built elsewhere. Say, a nearby parking structure on Ellsworth Street. The entire footprint of the project could fit there, Smith insisted.

The university, however, doesn’t see that as an alternative to the People’s Park project. It already plans to build a housing project at the Ellsworth site.

Rachel Swan and Michael Cabanatuan are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: rswan@sfchronicle.com, mcabanatuan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @rachelswan, @ctuan

VISUAL ESSAY: A look at protests at Berkeley’s People’s Park in 1969 and 2022.