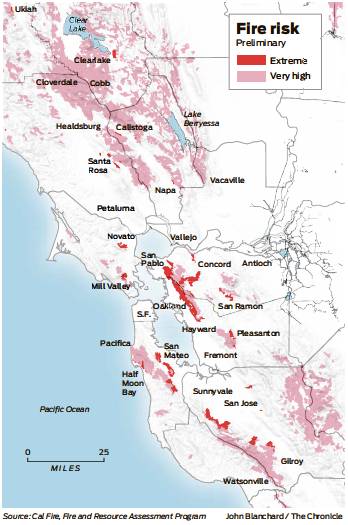

Mapping riskiest Bay Area wildfire locations

Cal Fire project highlights critical dangers to help towns prepare

By Julie Johnson

The first radio dispatch reporting a vegetation fire on a day in late May put the blaze in the hills on the eastern rim of the Napa Valley, an area that had burned just five years ago in a massive firestorm.

From his office, Division Chief Brian Ham with the Napa County Fire Department clicked on the video feed from a wildfire camera perched atop a hill overlooking the Napa Valley. A thin gray smoke column was rising from the bottom of a drainage.

Fire tends to race uphill — especially when buffeted by winds. Ham jumped in his truck. His colleagues first at the scene were already calling for reinforcements.

There’s no way to predict exactly when and where the next wildfire will ignite, but fire officials and residents across the Bay Area know the hot spots especially vulnerable to any spark. In these places, the roads are narrow, the vegetation is dense, and homes are intermixed with forests. Ham said that’s every community nestled into the hills along the Napa Valley.

“For me, there’s no one area to worry about — I’m on high alert for every fire in every place,” Ham said.

The ongoing drought, minimal snowpack, parched vegetation and hot, dry weather are all conditions that put California on track for another “very, very challenging wildfire year,” said Mark Ghilarducci, director of the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services.

Cal Fire scientists are revising statewide maps to help towns identify the areas at greatest risk of disastrous fires. They include the obvious clues: neighborhoods abutting forests and grasslands. They are adding elements such as topography, fire history, plus brush and tree types to further hone in on the greatest hazard zones. Cal Fire is meeting with local governments to fine-tune the maps, which are to be finalized and published in the fall.

Dark red blotches cover parts of east Santa Rosa, Pacheco Valle in Novato, western Martinez, towns on the northeastern flank of the Santa Cruz Mountains. The entire Oakland hills.

Daniel Berlant, a deputy director at Cal Fire, said the agency is improving these maps to reflect “significant changes in our climate” over the past decade.

Weather is the final ingredient for fire risk. And officials are constantly adjusting their models to account for factors such as wind, which has an enormous effect on fire behavior.

“To be honest with you, every hour we’re taking into consideration different weather factors and burn probability,” Berlant said.

Even the foggy coast is ripe to burn.

San Mateo County had seen little fog the week leading up to a dry lightning storm in August 2020 that ignited fires throughout Northern California, according to Jonathan Cox, a Cal Fire deputy chief in the county. Major blazes exploded from Mendocino National Forest to the Santa Cruz Mountains.

The neighborhoods along the northeastern flanks of the Santa Cruz Mountains are shown on fire risk maps in deep red, but so is El Granada on the coast home to the big surf Mavericks contest.

“When the fog’s not here, we’re very susceptible to fire,” Cox said.

In Sonoma County, the west county typically tempered by coastal fog hasn’t experienced much fire in generations. The region has dense forests and homes on narrow one-way-in-and-out roads. That’s the zone that worries Sonoma County Fire Chief Mark Heine, though he emphasizes the risk “is everywhere.”

Heine said they look at what are called energy release models, which use readings of moisture in plants and other factors to predict how ferociously a fire would burn. The models “are at historic highs right now.”

The 570-acre Old Fire in Napa County, which sparked May 31 and was contained June 5, is the third-largest blaze so far this season in Northern California. PG&E reported a problem with one of its lines in the region, though it’s unclear whether that was triggered by the fire or created the spark that caused it. The fire’s cause remains under investigation.

“Sonoma County all the way to the Oregon border went under extreme risk for high intensity fires in June,” Heine said.

Narrow roads make it difficult to get people out and firefighters in, adding risk for neighborhoods up and down the Oakland hills. Homes are close together in these neighborhoods, and the forested atmosphere that makes these places beloved also put them at risk, said Heather Mozdean, deputy chief of operations with the Oakland Fire Department.

“Park like your life depends on it — pointed so you can get away,” Mozdean said.

On the northeastern flanks of the Oakland hills, Contra Costa County authorities have been building shaded fuel breaks — where the ground vegetation is cleared and lower limbs removed from trees — to help prevent fire encroaching from the west.

Fire season never really ended in the county where more than 420 acres have burned so far this year, mostly on grasslands and ranchlands, Contra Costa Fire Protection District spokesman Steve Hill said.

More than 500 homes were evacuated before dawn Friday when a vegetation fire broke out in open space behind a Pitts-burg neighborhood. Fueled by wind, the fire burned right up to the backyards of dozens of homes. Hill said firefighters were able to beat back the flames because the neighborhood had taken pains to clear brush between homes and the open space. The fire charred 122 acres.

“It’s no different in Contra Costa County than it is in the north,” where the Old Fire burned, Hill said. “The urbanwildland interface — we have all of that. We have very high fire severity threat zones. We’ve had good fortune but we know the risks.”

In Solano County, Vacaville Fire Chief Kris Concepcion recalls watching 40-foot flames approach the Alamo area on the northeastern outskirts of town during the lightning fires of 2020. The success at keeping the fire from burning more than a 200-foot section of fence was luck — no wind — mixed with good planning. The fire burned out of Pleasants Valley into a basin that had been aggressively cleared.

In May, the Quail Fire forced dozens of people to evacuate in a rural area west of Vacaville. The fire was stopped at 135 acres.

No structures were lost and it burned through parched ranches and wildlands.

“That’s where we’re worried,” Concepcion said.

San Francisco Chronicle staff writer Emma Talley contributed to this report.

Julie Johnson (she/her) is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: julie.johnson@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @juliejohnson.