CHRONICLE INVESTIGATION BROKEN HOMES

TRAPPED IN MISERY

San Francisco spends millions to shelter its most vulnerable residents in dilapidated hotels with little oversight or support. The results are disastrous

By Joaquin Palomino and Trisha Thadani

For two years, this has been Pauline Levinson’s home:

A run-down, century-old hotel in the Tenderloin, where a rodent infestation became so severe that she pitched a tent inside her room to keep the mice away.

Where residents have threatened each other with knives, crowbars and guns, sometimes drawing police to the building several times a day.

Where, since 2020, at least nine people have died of drug overdoses. One man was discovered only after a foul stench seeped from his room into the hall.

Levinson is one of thousands of poor, sick or highly vulnerable people left to languish and at times die in unstable, underfunded and understaffed residential hotel rooms overseen by a city department that reports directly to Mayor London Breed, a yearlong investigation by The San Francisco Chronicle found.

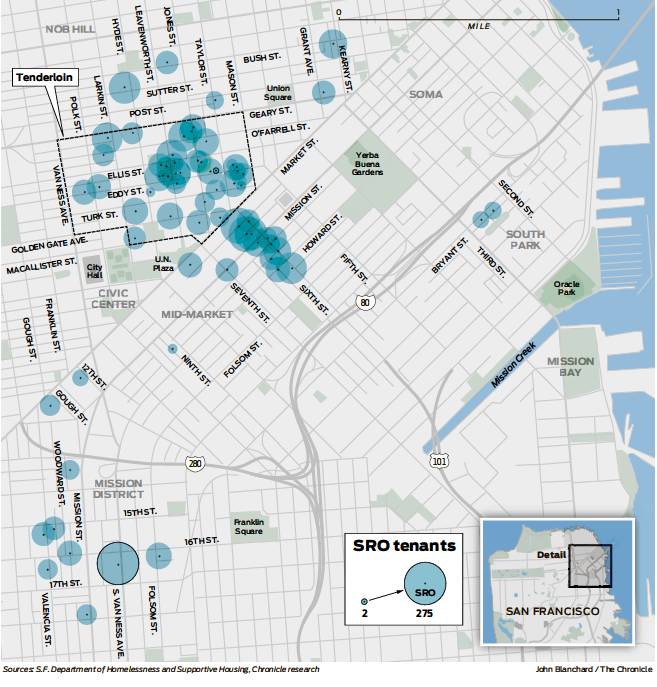

In a complex arrangement, the city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, or HSH, pays nonprofit groups to provide rooms and aid to formerly homeless people in about 70 single-room-occupancy hotels, known as SROs, which the nonprofits generally lease from private landlords. The buildings are the cornerstone of a $160 million program called permanent supportive housing, which is supposed to help people rebuild their lives after time on the streets.

But because San Francisco leaders have for years neglected the hotels and failed to meaningfully regulate the nonprofits that operate them, many of the buildings —which house roughly 6,000 people — have descended into a pattern of chaos, crime and death, the investigation found. Critically, the homelessness crisis in San Francisco has worsened.

To understand why more and more people are homeless despite a broad and expensive push to house them, Chronicle reporters obtained tens of thousands of pages of inspection records, incident reports, city contracts, police records and internal city emails through the California Public Records Act. They spent months interviewing more than 150 supportive housing tenants and employees — many of them in buildings operated by the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, the city’s biggest nonprofit SRO operator — and observing conditions in 16 hotels.

Among the findings:

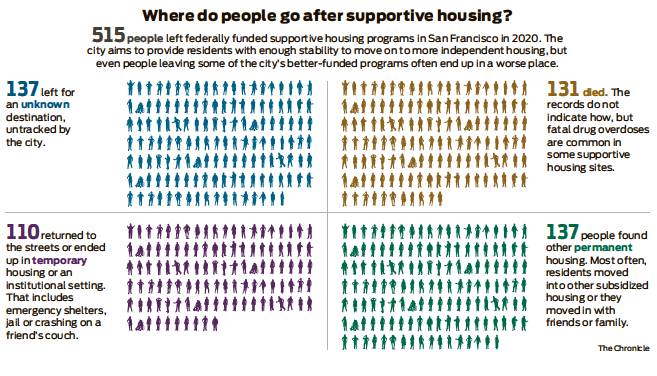

» HSH says its goal is to provide some residents with enough stability to enter more independent housing. But of the 515 tenants tracked by the government after they left permanent supportive housing in 2020, a quarter died while in the program — exiting by passing away, city data shows. An additional 21% returned to homelessness, and 27% left for an “unknown destination.” Only about a quarter found stable homes, mostly by moving in with friends or family or into another taxpayer-subsidized building.

» At least 166 people fatally overdosed in city-funded hotels in 2020 and 2021 — 14% of all confirmed overdose deaths in San Francisco, though the buildings housed less than 1% of the city’s population. The Chronicle compiled its own database of fatal overdoses, cross-referencing records from the medical examiner’s office with supportive housing SRO addresses, because HSH said it did not comprehensively track overdoses in its buildings.

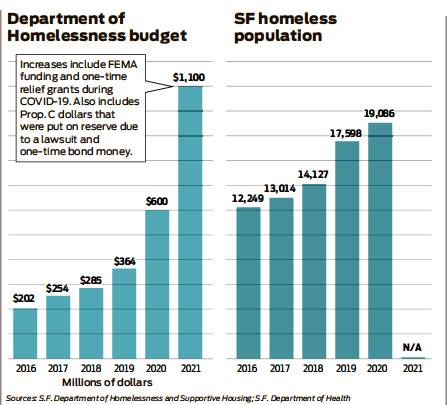

» Since 2016, the year city leaders created the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing, the number of homeless people in the city has increased by 56%, according to data exclusively obtained by The Chronicle that shows how many people accessed services. At least 19,000 people were homeless in San Francisco at some point in 2020, the most recent year for which data was available from the health department.

» Residents have threatened to kill staff members, chased them with metal pipes and lit fires inside rooms, incident reports show. At the Henry Hotel on Sixth Street, a tenant was hospitalized after a neighbor, for a second time, streamed bug spray into their eyes, public records show. Last May, less than a mile away at the Winton Hotel, a resident slashed another tenant’s face with a knife, leaving a trail of blood out of the building. Much of the instability stems from a small group of tenants who do not receive the support they need.

» Case managers who support SRO residents have overseen as many as 85 tenants apiece in recent years — five times higher than federal recommendations — in part because residential hotels receive as little as $7 a day per room for supportive services. That’s far less than the $18 per day per unit that HSH says is necessary for proper staffing for tenants seeking health care, job training and other assistance. Meanwhile, most of the caseworkers make well below a living wage; some are on the verge of homelessness themselves.

» Broken elevators trap elderly and disabled tenants on their floors, shuttered bathrooms force people in wheelchairs to rely on portable hospital toilets, and water leaks spread mold and mildew through rooms. Since 2016, city building inspectors have cited supportive housing SROs for more than 1,600 violations. Despite these problems, HSH has at times allocated hundreds of thousands of dollars less in annual funding for maintenance, repairs, and the hiring of workers like clerks and janitors than what the agency itself has deemed adequate.

» In 2019, the Board of Supervisors considered a ballot measure to create an oversight commission for HSH, which has 192 employees and one of the largest budgets among city agencies. But Breed lobbied against it, saying a commission would create more bureaucracy and that it was important she maintain direct control of the department. The measure died.

» HSH pledged to create a metrics-driven system to hold its nonprofit operators accountable by 2019. Yet Breed has allowed the department to push back this self-imposed deadline twice. HSH officials acknowledged in October that they had not issued a single plan of correction to housing providers, even as some programs have fallen egregiously short.

Left in decrepit buildings with little support, many SRO residents have become increasingly desperate.

Timothy Isaiah, 57, whom the city placed on an upper floor of the West Hotel even though he uses a wheelchair, said he repeatedly missed chemotherapy for his prostate cancer last year when a broken elevator trapped him in his room. Public records and interviews confirm that the elevator was inoperable for six weeks this winter.

Blocks away, at the Baldwin Hotel, Richard Brustie said he became so fed up with the conditions that he and his girlfriend left in January. They opted to live in a tent outside instead.

“I moved in there and the kitchen sink had human shit in it, and the hotel has black mold,” said Brustie, also 57. Past public inspection records confirm similar violations in the Baldwin’s common areas. “So we said screw that, and we started sleeping on the streets.”

After The Chronicle made repeated requests to interview the mayor, Breed — who was briefed by HSH on the findings of this investigation — was made available to speak to reporters by phone for 13 minutes.

The mayor acknowledged that many of the city’s SROs have issues and said people “should not have to live in these conditions.” She blamed the nonprofit operators and called for them to receive more scrutiny — a case she has been making since 2018 when she ran for mayor.

“It’s important that we make sure that the resources we’re providing are being used for the purpose that they’re intended to be used for,” Breed said.

Asked why she has not pressed HSH to hold nonprofits accountable for conditions in the SROs, Breed largely blamed the coronavirus pandemic, which began nearly two years after she took office. Breed declined to comment on whether the city had underfunded some SROs, and said she did not have information in front of her that would allow her to say what she had done as mayor to improve the city’s most troubled buildings.

Shireen McSpadden, who became director of HSH in May 2021, said in an interview that she inherited an SRO stock that city leaders had inadequately funded for years. But, McSpadden added, she would rather see people inside than on the streets, even if it’s in a building that “isn’t quite as good as it could be.”

After The Chronicle inquired about the lack of corrective action plans issued to nonprofits, HSH said it had implemented two since December — the first since the department was created in 2016.

In addition, McSpadden said HSH is in the process of directing millions of dollars into the older SROs to attempt to create calmer, safer and better-maintained homes, while also requesting additional money from the mayor’s office in the upcoming budget.

“Every single time we make a decision, we’re making a decision about people’s lives,” McSpadden said. “As we do this, we may be saying, ‘We’re serving fewer people because we’re going to focus on making sure that our buildings are really in great shape.’ ”

More than a third of the city’s supportive housing SROs, including many that struggle with persistent problems and funding shortfalls documented by The Chronicle, are run by the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, or THC. Randy Shaw, the nonprofit’s director, defended his buildings as “high quality” and blamed the city for placing only the most high-need tenants in his SROs without providing adequate resources and staffing to support them.

“We throw all these people into our hotels who have no demonstrated ability to live independently, who have severe problems and need to be elsewhere,” Shaw said, adding that there’s often nowhere else for them to go.

When done right, permanent supportive housing is the most effective and humane way to address homelessness, according to years of peer-reviewed research. It can give people the stability, resources and attention to address problems that were aggravated by their time on the streets, including serious health conditions, drug addiction and poverty.

Some supportive housing SROs in San Francisco are relatively well funded, with bigger budgets to maintain buildings and clinically trained staff members who can meet residents’ needs. The city and several nonprofit organizations have also purchased their own hotels and spent millions of dollars to refurbish them with private bathrooms, kitchenettes, and modern plumbing and electrical systems.

Public records and interviews revealed fewer deficiencies and complaints in many of these programs.

But of the roughly 70 supportive housing SROs in San Francisco, reporters found that most were beset either by housing code violations, understaffing, persistent calls to 911, frequent drug overdose deaths or widespread complaints from tenants.

These properties have rooms that are often smaller than what the city allows for a standard parking space, in buildings where tenants typically share a bathroom and kitchen with neighbors. Many residents in these hotels struggle with drug addiction or have mental and physical disabilities, their lives upended by financial crises and other traumas.

The SROs are clustered in and around the Tenderloin, a neighborhood riddled with so much crime and open drug use that Breed in December declared a 90-day state of emergency there. By allowing people to live in such conditions, San Francisco has spent hundreds of millions of dollars but still failed to help those most in need — and only hindered its efforts to tackle the ever-worsening homelessness crisis.

“We’re shooting ourselves in the foot,” said Margot Kushel, a UCSF researcher and national authority on best practices in supportive housing. “We can’t (house) people who are incredibly high-risk and not give them the services they need. It will not work.”

Breed is not the first city leader to rely on Tenderloin SROs to house homeless people. One mayoral administration after another has used the properties to get as many people off the streets as quickly as possible, while failing to address the living conditions inside. San Francisco’s debilitating affordability crisis and fierce resistance from residents to creating supportive housing in wealthier neighborhoods have fueled the approach.

During her 2018 campaign for mayor, Breed — who regularly invoked her own childhood in substandard public housing — promised to look closely at the city’s investment in homelessness services, the bulk of which goes to supportive housing. San Franciscans “deserve accountability,” she said shortly after she was elected.

Last year Breed pledged to take San Francisco’s supportive housing system in a new direction. She expanded the distribution of rental vouchers so more people can live outside of Tenderloin SROs, and boosted funding for support services and maintenance in newer programs — most of which have private bathrooms and in-unit kitchenettes.

“That is so important,” she said this month at a news conference for the Garland Hotel, a newly renovated SRO. Officials showed reporters a spacious room with two large windows, a private bathroom and a kitchenette with a stone countertop. “I want us to move towards places like the Garland … that will allow people to live in their own space, and live their lives with dignity.”

Yet Breed has made the same political calculation as her predecessors: pour money into new programs while overlooking the thousands currently living in underfunded hotels.

While the bulk of her budget this year comes from Proposition C — a 2018 business tax that may be spent only on new homelessness services — Breed has made relatively little additional funding available during her four years in office to improve the existing SROs. Less than 2% of the current homelessness budget will be spent boosting services in older supportive housing sites.

Tenants and advocates fear the city will create a two-tiered system: In new programs created under Breed, people will live in better-maintained buildings in safer neighborhoods and receive far more help as they try to move on from their time on the streets. In the older programs, people like Pauline Levinson will continue to struggle.

Levinson, who attended Lowell High School and San Francisco State University, wound up at the Jefferson Hotel in 2020 after leaving an inpatient drug-treatment program. When the city offered her a room for $500 a month, she envisioned a stable home where she could re-establish relationships with her three children and save up for an apartment.

Instead, at the hotel in the heart of the Tenderloin, ceilings have collapsed on tenants, thieves have stolen from their rooms, and bedbugs have left welts on their arms and legs, according to public records and interviews with 15 residents.

Haunted by the death of a good friend in the building, Levinson said she recently tried to retrieve the woman’s belongings from the trash room after staff members threw them away. But they had already been soiled by garbage.

Levinson is deteriorating, she acknowledges. After slapping a friend in the hallway, getting into arguments with neighbors and staff members and racking up noise complaints, she is fighting the Tenderloin Housing Clinic’s attempt to evict her. Levinson and the nonprofit agree she would be better off in a smaller building with more support — but such options are rare in San Francisco.

“I’ve got to get out of here,” she sobbed one day in January. “This is a nightmare. People give up in these places. There really is no hope.”

* * *

Fifteen years before Levinson moved into the Jefferson and more than a decade before Breed took office, a young mayor with lofty political goals made an eye-popping proposal. He was going to end the worst of San Francisco’s growing homelessness crisis within a decade.

That politician is Gavin Newsom, now the governor of California.

A major pillar of his plan was a city ballot measure known as Care Not Cash, which would slash monthly welfare payments to homeless people by hundreds of dollars, to as little as $59. The new policy — based in part on the belief that generous cash payouts drew homeless people into San Francisco and funded drug use — launched in 2004, the same year Newsom became mayor. In exchange for less money, people would be offered a place to stay.

But there wasn’t enough housing available. Scores of people were reportedly stuck in emergency shelters, with little money and nowhere else to go. Sister Bernie Galvin, a Roman Catholic nun who advocated for the homeless, told reporters before the launch of Care Not Cash that it was “heartless, ruthless and basically immoral.”

Facing backlash, Newsom scrambled to find housing. The solution: His administration would secure the 100-year-old residential hotels concentrated in the Tenderloin and South of Market, or So-Ma.

Built mostly in the aftermath of the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906, these hotels first housed seafarers, dock workers and other laborers. With sparse amenities — small rooms, thin walls and shared bathrooms — the hotels were frequently used for temporary stays as the city’s new arrivals saved for better housing or followed work elsewhere.

Beginning in the late 1940s, most of the properties were torn down or converted to make room for apartments, office buildings and tourist hotels. Many of those that remained fell into disrepair; welfare officials started using the rooms as shelter for the unemployed and elderly.

Then, starting in the 1980s, the state and federal governments slashed billions of dollars in funding to subsidized housing programs and mental health services. As rents in San Francisco soared and affordable housing options like SROs shrank, thousands of people were forced out on the streets.

By the early 2000s, the city said roughly 8,640 people were homeless in its biennial count, meaning they were living either outside, in an emergency shelter, or in other tenuous circumstances.

Similar to today, sleeping bags lined downtown sidewalks, prompting outrage from business groups and residents who pressured Newsom into action. His administration worked with nonprofits to purchase SROs or — more often — to negotiate long-term contracts with their owners to house homeless people.

Leasing buildings was far faster and cheaper than buying buildings, or constructing new ones, especially in pricey San Francisco. Strict laws that prevented demolishing SROs or flipping them into tourist hotels or apartments unless the owners paid a hefty fee also meant the properties were here to stay, though many of them were mostly vacant. They could remain underutilized structures for the city’s poorest residents, or be used to house homeless people.

The arrangement, called master leasing, is a boon for building owners, who can secure more than $1 million in rent each year. About 15% of the leased SRO units were funded by the local health department and provided robust on-site support. The rest, including the Care Not Cash hotels, were overseen by the city Human Services Agency and offered much less help.

Still, in 2008, a city audit concluded that Care Not Cash was “generally achieving its goals” by moving people indoors, keeping them housed, and offering mental health and drug treatment services. Newsom told reporters it was “a story of success beyond our imagination.”

“Thousands of people were being helped by this,” Steve Kawa, chief of staff for both Newsom and his successor, Mayor Ed Lee, said in an interview last year. “And it’s not just that they have a place to live that’s clean and safe — but they’re also getting the care they need to have as human beings.”

But by 2011, when Newsom left San Francisco to become lieutenant governor, the number of homeless people in San Francisco had remained unchanged. That left Lee, the newly appointed mayor, facing the same political dilemma of thousands sleeping on the streets and increasing demands to do something about it.

Like Newsom — who through his office declined to be interviewed for this story — Lee looked to SROs in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

But as the city approved contract after contract, it became apparent the approach was falling short. From 2014 to 2016, several audits and public reports found a lack of on-site support and oversight in the SROs.

Case managers’ interactions with residents were often limited to just a few referrals for basic services or written notes about paying rent. Insufficient monitoring by city agencies made it difficult to “track the actual outcomes of supportive housing residents and whether supportive housing programs are effective,” a report by the city Budget & Legislative Analyst’s Office warned.

In master-leased SROs overseen by the Human Services Agency, two-thirds of tenants left within three to four years. Alarmingly, many appeared to wind up homeless again: According to the report, they increased their use of homelessness and emergency services or landed in jail, suggesting that their situation had “worsened.”

A separate study on all SROs by the local health department noted that some hotels were so neglected that “even the most basic functions like bathing, accessing food, and socializing were a struggle” for residents.

Faced with growing calls to fix the system, Lee — who died of a heart attack in 2017 while in office — announced a plan to transform San Francisco’s response to homelessness.

He moved oversight of the SROs and other homelessness programs from a tangle of city agencies to just one: HSH. Lee pumped the new agency’s budget with $202 million — the majority of which went to supportive housing — and promised that the city’s investment would lead to better coordination and results.

By 2020, the mayor said, the city would end homelessness for thousands of San Franciscans.

“We will not move them from corner to corner. We want to have sustained support for them,” Lee said at a 2015 news conference, standing in the lobby of the newly refurbished Baldwin Hotel on Sixth Street in SoMa. “This is a world-class city, and we have a world-class heart.”

* * *

Christopher Harris’ room was infested with mice and cockroaches, and was so small that when he stretched out his arms, he could nearly graze the opposite walls with his fingertips. This was the Baldwin Hotel in the summer of 2020, five years after Lee’s news conference.

The city had placed Harris, 29, at the Baldwin after the car he was living in broke down. A few months later he was moved to a slightly larger unit near the trash room, which overflowed with so much garbage that the door wouldn’t shut, filling his room with a putrid odor that he tried to mask with candles and incense.

A group of neighbors standing on the sidewalk outside the Baldwin complained of vermin, leaking ceilings and clogged toilets, issues that were previously cited in building inspection records. One man in a wheelchair told The Chronicle his room was so slanted that he rolled across it.

“I really hate it,” Harris said in an interview in June. “It makes me really sad, depressed, isolated.”

A Chronicle analysis of data from the city’s building inspection agency found that since 2016, San Francisco’s supportive housing SROs have been cited for at least 1,600 housing or building code violations. A review of thousands of pages of health department reports revealed scores of additional hazards.

HSH has not adequately funded maintenance in many buildings, or stepped in when nonprofits and private landlords responsible for addressing bigger structural issues have failed to make quick repairs. As a result, these shortcomings have been allowed to fester with few consequences, the investigation found.

The citations reviewed by The Chronicle cover everything from missing room numbers to ceilings on the verge of collapse, yet offer just a glimpse into the conditions of many hotels. During visits to 16 SROs, reporters observed dozens of issues that were not investigated or cited by inspectors: a sweltering room heater stuck at 81 degrees; a pitch-black fourth-floor bathroom without power; the door to a vacant room taped shut, cockroaches spilling out of it.

At the Mission Hotel last summer, a cat jumped through the open window of Anthony Alexander’s ground-floor unit and parked itself in front of a hole in the molding. Mice scurry out of the wall so frequently, Alexander said, that the cat knows it just has to wait. Health inspection records show the Mission Hotel has previously been cited for rodent issues.

More than 1,100 of the violations cited by building inspectors in city-funded SROs were related to unsanitary living conditions or general disrepair. “Absolutely brown” water flowed from a sink faucet; “thick mold” covered a room; and a vinyl floor “appeared to be held in place by tape,” inspectors said.

In at least 68 documented cases, elevators were out of service for days or weeks, removing a lifeline for people dependent on wheelchairs and walkers. Some tenants have had to call the Fire Department to get someone to carry them up or down the narrow stairwells, incident reports show.

At the Cadillac Hotel in January, an elderly resident sat on the bottom step, unable to make it up to his room. The elevator was inoperable, according to inspection records. The Cadillac’s nonprofit owner and operator, Reality House West, did not return repeated requests for comment.

“There is no place for SRO tenants to go — there is no up,” said Mark Parsons, 67. He suffered a stroke last year and struggles to walk up the stairs whenever the elevator breaks at the Cadillac in the Tenderloin. “They are just a forgotten class of people, and I’m one of them.”

Eighty of the violations since 2016 cited a lack of services: shuttered bathrooms; heaters that either didn’t turn on or wouldn’t shut off; shower grab bars hanging off walls.

At the Hillsdale Hotel on Sixth Street, hot water was out for at least a week over the winter, prompting inspectors to call for an administrative hearing to speed repairs. Episcopal Community Services, a major supportive housing provider that manages the Hillsdale and Henry hotels, declined several requests for an interview.

Shaw, executive director of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, said he regularly visited his hotels before the pandemic and did not see problems with maintenance and upkeep. When there are issues, Shaw said, his staff and the building owners address them as quickly as possible.

Shaw blamed residents for some of the violations documented by The Chronicle. He said some SRO tenants have hoarding disorder, a mental health condition marked by difficulty discarding possessions, and that this behavior attracts pests — an issue frequently cited in public health reports. Other residents have vandalized buildings and drilled holes in their units, he said, resulting in citations.

“Is every person a victim?” Shaw asked. “There’s no question that there’s a greater challenge housing our population because of the difficulties with the tenants themselves.”

But The Chronicle found that many residents do not contribute to the substandard living conditions to which they are subjected. Rather, these conditions put a heavy burden on people already dealing with physical and mental health challenges.

In January, at the Jefferson Hotel, Tony Evans showed a reporter how he must struggle to pull a small refrigerator out of his closet to sweep away mouse droppings that build up. Evans, who’s disabled by a back injury, said he goes through the same precarious routine three times a week.

A health inspector in December confirmed that mice had come into some tenants’ units when they left their doors open to air their rooms out.

Down the hall, Joseph Atchan pointed to a rough patch in his ceiling where he said it had recently collapsed, raining debris on him and cutting his hand. He showed reporters a photo of the damage. As he spoke, his clothes hung from a thin ledge above his bed; there was no other space for them in his small unit.

“They just put people in these places — they don’t ask them what they need, they don’t help them out, they just leave them stuck,” Atchan said.

City contracts require nonprofit organizations to maintain their buildings in “sanitary and operable condition.” They must frequently clean common areas, remove trash, provide pest control, and repair smaller plumbing and electrical issues.

A large chunk of the money they receive from the city — as much as $1,100 per month per unit — often goes straight to the buildings’ private owners to cover the leases. These owners are typically on the hook for major repairs, like fixing inoperable elevators and structural problems, though public records show it can take weeks or even months for them to address these issues.

Dipak Patel, who owns several supportive housing SROs leased to the city, said the delays are often out of his control because major repairs can take time, especially in century-old buildings.

For example, the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corp., the nonprofit that owns and operates the West Hotel, said repairs were held up on the broken elevator that stranded Timothy Isaiah in his room, in part because the pandemic delayed the delivery of parts and state inspectors took weeks to sign off on the work.

Meanwhile, some nonprofit directors say the remaining funds aren’t enough to promptly fix all of the problems, let alone properly staff the buildings with janitors and maintenance workers.

After paying rent to property owners and hiring case managers, some building operators are left with as little as $740 per unit each month to clean common areas, make repairs, turn over rooms and provide 24-hour front desk staffing — 33% less than the standard funding for programs opening under Breed today. When things break, nonprofit officials say, there’s often not enough money or staff to quickly fix them.

“If you can’t have desk clerks, janitors, case managers and maintenance workers, you can’t make this model work,” said Lauren Hall, co-founder and director of DISH, or Delivering Innovation in Supportive Housing, a nonprofit that manages some of the city’s better-funded SROs. “It’s not a model that’s broken. It’s a model that’s under-resourced.”

Presented by The Chronicle with a detailed breakdown of the funding disparities in supportive housing, HSH officials said they were in the process of adding roughly $3.4 million for “repairs and improvements” across all of their master-leased hotels, as well as for deep cleaning and increased janitorial staff at certain properties.

Still, in some cases, the problems can’t be entirely explained by funding: At the Baldwin Hotel, where Christopher Harris lived, the THC was authorized to receive $3,300 to $3,600 per month in rent payments and taxpayer dollars for each unit last year — about $1,000 more than the average rent of a studio apartment currently on the market in San Francisco.

That funding is higher than at most of the THC’s other properties because of millions of dollars in federal support to house chronically homeless adults with diagnosed disabilities.

Despite the large price tag, inspections and complaints at the Baldwin unearthed a mountain of problems in the past six years, according to city reports: feces in the communal showers; a sink hanging off a wall; a broken elevator that forced staff to deliver food to tenants stuck on upper floors; and an elderly disabled man living amid a “tremendous amount” of cockroaches.

Through interviews and by obtaining internal HSH emails, reporters learned of at least three separate instances in which tenants fled the building to sleep outside.

“Residents were saying all the time that it was worse than being on the streets,” said Lizz Cady, a former employee who oversaw support services for the Baldwin when it first opened.

Shaw denied that the nonprofit was responsible for the conditions inside the Baldwin. He blamed the city, saying leaders never should have placed such a high-need population there. The building has nearly 200 units and extra-small rooms, and is located on a crime- and drug-ridden stretch of Sixth Street.

Living conditions became so untenable that, in 2018, the THC — not HSH — attempted to sever its contract, worth up to $7.7 million per year, to run the Baldwin. In emails, the nonprofit’s deputy director told the city agency that it could not provide its “standard level of services” and that “tenants and staff feel unsafe.”

HSH increased the number of counselors and decided to leave at first 25 — then 55 — of the SRO’s rooms empty, but the problems persisted. In a 2019 annual report, THC staff said fights were common and maintenance staff had a hard time staying on top of frequent property damage.

Harris, struggling to adjust to life inside the Baldwin, was kicked out last July for fighting with other residents. “God is just trying to take me to a better place,” he said before lugging his belongings down to the street. “This place is really evil.”

By November, Harris and his small dog were homeless again, living out of a sedan with a shattered back window.

Then in December, after years of warnings and complaints, HSH and the THC finally agreed to stop using the Baldwin for permanent housing.

Their decision was based on a shared understanding: It was an unsuitable place for people to call home.

* * *

When London Breed ran for mayor in 2018, she made a promise: Her administration would audit the city’s spending on homelessness services, making sure nonprofit organizations were holding up their end of multimillion-dollar contracts.

“We need to understand what we’re doing now, whether or not we’re making the right investments and, more importantly, what is our long-term plan of action to address these issues,” she told KQED in October 2018, four months after she won the mayoral race.

HSH had been created in part to oversee San Francisco’s investment in services such as supportive housing. Officials would define what success looked like, then “drive our resources toward programs that meet the city’s strategy and the city’s priorities,” said former director Jeff Kositsky, speaking just before the agency launched. (Kositsky, who ran the department for four years, declined to comment for this story.)

In 2017, officials said they would develop comprehensive performance measures for all nonprofit contractors. HSH said it would put this enhanced oversight in place by the end of 2019 — and the need was urgent.

The agency planned to adopt a system called coordinated entry that would prioritize placing the most vulnerable people in supportive housing — those who had been on the streets longer and had more challenging health needs.

But today HSH has created only limited guidelines to determine how effective its programs are, a 2020 audit found, even though such standards were supposed to be in place more than two years ago.

As the first deadline for that metrics-driven plan neared in December 2019, HSH officials said they needed more time. They pushed their self-imposed deadline back until summer 2021. Breed allowed the delay.

Then, last summer, HSH director McSpadden told supervisors that her department would push back the accountability system’s debut again, in large part because of the pandemic. In an interview this month, she said HSH plans to have detailed goals and requirements folded into all new contracts by June 2023.

Breed acknowledged that specific performance goals are a “key component missing in terms of accountability,” and that she expects nonprofits to alert HSH to issues as they come up.

In the absence of stringent monitoring, the city has relied heavily on short reports filled out by supportive housing providers to measure success. These include self-reported data that is not independently verified by HSH — surveys that claim tenants are overwhelmingly happy with their housing, even in some buildings where The Chronicle uncovered serious concerns from residents.

Supervisor Matt Haney, whose district includes the Tenderloin and SoMa, tried to add a layer of supervision to HSH in 2019. The supervisor — who said his office receives a flood of complaints about conditions in supportive housing sites — proposed the creation of an oversight commission, similar to those that regulate San Francisco International Airport and the Recreation and Park Department.

Under Haney’s original proposal, the commission would have approved or declined most supportive housing contracts — those over $200,000 — before passing them to the Board of Supervisors for a final vote. Moreover, it would have gained the power to hold the agency accountable by, for example, opening an investigation into its activities or firing the department head. And the commission would have created a central public forum where tenants could share their grievances.

“When you don’t have oversight or regular audits, it’s hard to ensure quality and results,” Haney said. “We should have clear metrics and strategy, and that’s not in place right now.”

But Breed was “strongly opposed” to the idea, he said, because she “felt that putting in a commission makes it more challenging for her to be accountable for results.” Haney said Breed spent months lobbying his colleagues against it.

The measure, which required voter approval, needed six supervisor votes to qualify for the November ballot. On July 23, 2019, Supervisors Haney, Gordon Mar, Hillary Ronen and Shamann Walton voted to place the proposal on the ballot in that upcoming election.

But seven supervisors — Vallie Brown, Sandra Lee Fewer, Rafael Mandelman, Aaron Peskin, Ahsha Safaí, Catherine Stefani and Norman Yee — voted to delay consideration of the measure until a future election cycle, effectively killing the proposal.

In an interview, Safaí said he is generally supportive of the idea of a commission. But he said he agreed to delay the measure in 2019 because he wanted more time to consider the proposal amid “strong opposition” from the mayor’s office.

Breed told The Chronicle this month that she had opposed the commission because it would have added “another layer of bureaucracy that can make it difficult for us to try and do the work that we’re here to do.”

Nearly three years later, Haney, who was elected last week to the California Assembly, has not revived the proposal. He said he did not have enough support and that the pandemic — which struck several months later — distracted the board with other priorities.

Today, HSH is the largest agency in the city without an oversight body.

* * *

Left with scant monitoring and inadequate staffing and resources, many SROs have been overwhelmed by the same issues — mental health crises, crime and addiction — that they are supposed to be calming through stability and support.

The Chronicle reviewed police reports, records from the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner and nearly 900 critical-incident reports that nonprofits must fill out whenever there’s a serious emergency in their buildings. They found that police and emergency medical technicians respond to some SROs every other day on average.

In 2020 and 2021, at least 166 people died of drug overdoses in supportive housing hotels, devastating residents and staff members, The Chronicle’s investigation found.

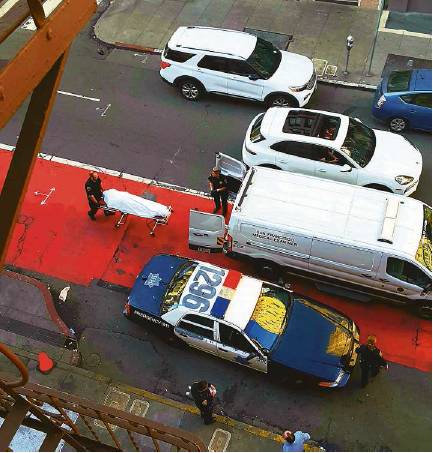

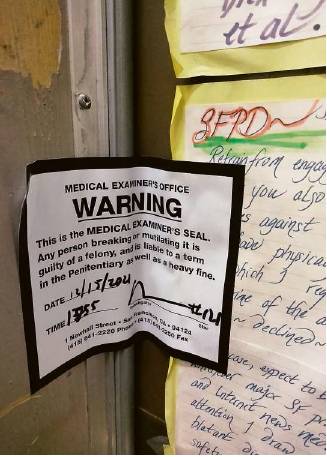

At the Baldwin Hotel last June, a tenant recalled seeing a man running down the hall yelling for Narcan, the nasal spray that reverses opioid overdoses, crying out that his girlfriend was turning purple. He wasn’t able to help her in time: She died, city records confirmed. The medical examiner came to cordon off the room.

Months later, at the Mission Hotel, flies swirled around the lobby as a minister held a service for two residents who had recently passed away. A stream of tenants shuffled through, glancing at the bouquets of plastic flowers on a small altar, but few stopped to participate in the all-too-familiar ritual.

In a February hearing, HSH officials acknowledged that living amid so much death is traumatizing for tenants and staff.

Increased prevention efforts, including installing hallway dispensers for Narcan, have helped bring down the number of fatal overdoses from a peak in 2020, officials said. Because it can take months for the medical examiner to determine a cause of death, complete data from last year is not available, but partial records show a decline in fatal overdoses across the city, including in SROs.

Still, HSH said at the hearing that it doesn’t track how many people overdose in supportive housing programs. In an interview this month, McSpadden said the agency is developing a monitoring system. She added that HSH is implementing an overdose prevention policy that, among other things, mandates additional training for SRO staff.

The problems go far beyond overdoses.

Thieves have ransacked tenants’ rooms, and residents have been assaulted with golf clubs, hammers and other weapons. At the McAllister Hotel on the edge of the Tenderloin in June 2020, a resident tried to saw a passage into a neighbor’s unit. The nonprofit operator, Conard House, did not return requests for comment about the incident.

Some challenges are inevitable when dozens to hundreds of people — many with physical and mental health conditions — are packed into old buildings with little privacy and support. Residents often arrive in poor health, or struggle with long-standing substance use after years on the streets.

Yet in some cases, HSH has not taken even basic steps to ensure a safe and healthy environment.

When the city converted the Winton Hotel on O’Farrell Street in the Tenderloin into supportive housing in 2016, HSH said it would serve as a safe and calm refuge for about 100 formerly homeless people, including many military veterans.

But reporters, reviewing public records and interviewing 20 current and former residents, found that the building has become riddled with crime and disarray. Much of it, tenants say, has been caused by a small group of people who need far more attention and support than the SRO offers.

Emergency responders have been summoned to the hotel at least 740 times since it became supportive housing. Of these calls, 190 involved a potential threat to someone’s life or major property destruction, according to records kept by the Department of Emergency Management, which dispatches police, fire and medical personnel to 911 calls.

Last April, a resident said she was moving her belongings into a hallway to escape a bug infestation when smoke started to billow out of her neighbor’s room. A sofa was engulfed in flames, according to the police report, triggering the overhead sprinklers and flooding the fourth floor with rust-stained water.

The next month, loud shouts echoed through the hotel. When residents peered out of their rooms, they found blood splattered on the floor. According to a police report, a resident had forced his way into a woman’s room to retrieve a stolen tablet computer. In self-defense, she stabbed him twice in the face with a scalpel.

The man was arrested and charged with misdemeanor trespassing. The woman, residents said, was later evicted.

Current tenant Patricia O’Donnell, who was homeless for more than a decade before the city placed her at the Winton, said she was grateful to be inside, “but it’s crazy living in there. Police come all the time.” As a reporter interviewed O’Donnell last May, a squad car pulled onto the curb outside the building and two officers went inside. They needed to defuse a “high priority” fight, according to 911 logs.

Assaults and mental health emergencies persisted at the building through 2021, and four people died in the hotel.

“If you have any kind of trauma, (this building) is going to enhance it,” said Jonathan Nelson, who moved to the Win-ton in July after the city-funded SRO where he had previously lived was shuttered by a fire. At the Winton, he said, people have broken into his room and dogs have lunged at him in the hallways. “I don’t feel safe at all,” he said.

Under internal guidelines, HSH is supposed to conduct site visits at supportive housing programs that receive federal funding, like the Winton, if serious issues are identified. But records obtained by The Chronicle show that agency staff members have not physically inspected the hotel in more than three years.

In September 2018, when HSH monitors last went to the SRO for an inspection, they checked on the basic upkeep of common areas and reviewed administrative requirements, such as whether tenant files were up to date and properly stored.

HSH then skipped physical inspections of the Winton in 2019, 2020 and 2021. Officials said they typically conduct in-person inspections every other year and that the pandemic disrupted their plans.

Instead, officials asked THC employees to complete a 15-question checklist attesting that they had met basic administrative duties, such as creating an emergency response and disaster plan.

Shaw denied that there were serious problems at the Winton, which he called a “beautiful” hotel. He said that in general, much of the crime in his SROs stems from personal conflicts that his staff has little control over. The Winton and other buildings are generally calm, he said, except for a few high-profile incidents that draw too much attention.

“We’re a violent society,” Shaw said. “Let’s not act like there’s something unique about SROs.”

Longtime Winton resident Anthony Thorp said he has given up hope that city leaders will fix the issues at the building. He does not blame the violence and disorder on his neighbors — many of whom, he said, are not receiving adequate support — but on the THC for not helping these tenants, and on the city for not stepping in.

“They’re neglecting these people; they’re throwing them into a room like cattle,” Thorp said. “There are some really good, decent people who care about this building. But all the negatives wipe that away.”

* * *

Many of the problems in city-funded SROs are aggravated by severe under-staffing and wages so low that some nonprofit employees in the buildings are on the brink of homelessness themselves. This dynamic undermines the very point of supportive housing: to offer stability and attentive care for those most in need.

According to HSH’s guidelines, on-site counselors are supposed to work with a caseload of no more than 25 clients. That ratio gives staff members a chance to be a regular and reliable part of tenants’ lives, hosting events and connecting them with health care, job training and other services.

But The Chronicle’s investigation found that HSH seldom gives nonprofits enough funding to meet that standard —even as the city places some of the hardest-to-house people into SROs.

As a result, overworked counselors with annual salaries as low as $43,000 — well below what the federal government considers low-income in San Francisco — have little time to help residents overcome physical and mental challenges. Turnover is frequent, making it difficult for staff and tenants to build relationships and trust.

“They come and go,” said Jennifer Franklin, who moved into the Mission Hotel last summer after months living on the streets. “The one who did my intake, she was gone the next day. And then I had to meet another case manager, and start all over with my story.”

In 2020, the most recent data available, just 12 of the 42 supportive housing SROs that reported figures to the Department of Homelessness kept caseloads at or near a 1:25 ratio. Counselors working in at least 15 SROs handled 40 to 85 residents — so many that, according to experts in the field, they would have little time to offer meaningful assistance.

This lack of support exists even though the city moved forward in 2018 with coordinated entry, placing the people with highest needs into supportive housing.

Breed took office the year coordinated entry launched. Since then, supportive housing nonprofits have repeatedly raised concerns over the low pay and high caseloads: Though the adoption of coordinated entry placed more high-need residents in the hotels, they noted, the city did not alter those hotels’ contracts or provide more funding.

In public hearings, they have cautioned city leaders that staffing woes were threatening to undermine the very purpose of supportive housing. Employees, they warned, often had no choice but to call the police or threaten to evict the most challenging tenants.

Over the past four years, these nonprofit heads have asked for $26.6 million in additional funding to raise wages for the lowest-paid workers and improve services in their buildings, according to the Supportive Housing Provider Network, a membership group representing most nonprofit operators in the city.

But the Breed administration and the Board of Supervisors approved just $6 million in that period, effectively declining either to provide the nonprofits the resources they say they need or to hold them accountable for the poor conditions under the current funding. This amount was divided among all homeless service providers, including those offering street outreach, emergency shelters and housing.

The mayor’s office said in an email that city departments have had to tighten their budgets in recent years. Breed and the Board of Supervisors, the office said, receive “millions of dollars in requests for funding every year, far above what is available to spend from the general fund.”

In an interview, HSH officials said they are in the process of adding $1.1 million for support services across many supportive housing sites — though nonprofit providers have calculated that it would cost nearly four times as much just to raise salaries for all case managers to $58,000 per year.

Responding to questions about the 2020 caseloads, officials said they have since added case managers to some of the most understaffed hotels.

McSpadden said a new $9.8 million program run by the Department of Public Health and funded by Proposition C will also help by providing roving mental health services to tenants with the most significant needs. Prop. C funds can be spent only on new programs that help people who are currently homeless or prevent others from losing their housing.

The low salaries, challenging work conditions and constant turnover have frustrated people like Marissa Roarty, who said she has worked as a clinical case manager at several THC SROs that were short-staffed. When case managers are unable to proactively work with tenants, she said, problems often go unnoticed until they boil over.

In 2016, when Roarty was working at the All Star Hotel, she learned that a former resident was on an angry tirade in the Mission District and threatening Roarty’s life. “Where is she?” the man purportedly shouted as he barged into a nearby hotel. “I want to kill that bitch.”

Other residents have also threatened staff members at the All Star Hotel, critical-incident reports show.

For her safety, Roarty transferred to the Seneca Hotel on Sixth Street, but things didn’t improve there: The hotel’s small, dark rooms and dirty bathrooms set the Seneca’s residents on edge, she said. Inspection records show a history of plumbing issues in the hotel. Meanwhile, Roarty’s caseload nearly doubled, from 40 people to around 70.

“It’s hard to go beyond crisis management when you have such heavy caseloads,” Roarty said. “You’re putting on a Band-Aid rather than getting to the root of the issue.”

* * *

It doesn’t have to be like this.

Every other major West Coast metropolis — Los Angeles, San Jose, Seattle, San Diego, Portland, Sacramento — bases 30% to 68% of its long-term housing for homeless people in “scattered site” programs, according to a Chronicle review of U.S. Housing and Urban Development data. Through this approach, people typically use vouchers to rent apartments on the private market, then case managers help them adjust to their new lives.

“When people get to make choices about where they live — what neighborhood they want to live in or don’t want to live in — they’ll be more inclined to stay,” said Andrew Spiers, director of training and technical assistance at Pathways to Housing PA, a Philadelphia nonprofit that trains supportive housing providers in best practices.

Despite residents’ clear desire to live outside of a Tenderloin SRO —— where they must share a bathroom and kitchen with strangers and have strict restrictions on who can visit —— the scattered-site method has rarely been used in San Francisco. Last year, less than 11% of the city’s long-term housing units for homeless people were in such programs, by far the lowest rate of any large metropolitan region in the country, HUD data shows.

Experts have attributed the low rate to the city’s incredibly expensive rental market, leaving San Francisco overwhelmingly dependent on 100-year-old hotels concentrated in a few small neighborhoods.

While many of these buildings have fallen into disrepair, the city has proved that it knows how to do better. Some SROs are owned by nonprofits — rather than master-leased —— and have been newly renovated to include private bathrooms, kitchenettes and larger rooms. Experts widely agree that such improvements lead to more stability and better outcomes for tenants.

“When people get into housing, and it’s dignified and well run, we just see this massive transformation,” said Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness, a San Francisco advocacy group.“You can see it in people’s faces. They just look different — so much more rested, and the stress lines on their face disappear. … It’s just a really beautiful situation.”

In September, sunlight poured through a domed atrium into a bright, plant-lined lobby at the Kelly Cullen Community, a former YMCA that the nonprofit Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corp. spent more than $90 million to transform into housing for medically fragile homeless people.

A nurse tended to a resident with a deep cough, while the assistant manager greeted every person she saw. A flowering rooftop garden offered a calm escape from the frantic energy of the Tenderloin eight stories below.

The 172-unit building has rooms more than twice the size of those in most other SROs, with private bathrooms and kitchenettes. Five social workers, a licensed nurse, a psychiatric social worker and a money manager help residents adjust and stay healthy. Before the pandemic, staff members hosted movie nights, karaoke and other events in a renovated auditorium.

In the past year, Breed has pledged to open buildings that look more like Kelly Cullen. Using a record $1.1 billion budget for homeless services and a windfall in state grants, she plans to buy hotels with private bathrooms and, when possible, kitchenettes.

By owning rather than leasing these properties, the city can more easily complete critical building upgrades. The mayor’s administration is also providing these new hotels with far bigger annual budgets for support services and property management, though they will not have the same level of staffing as Kelly Cullen.

Breed has also funded about 1,000 rental vouchers, providing formerly homeless people with more choice in where they live.

However, Breed’s massive investment will do little to improve the living conditions in SROs like the Jefferson and the Winton.

The $1.1 billion is earmarked almost completely for new programs, because much of the money comes from Prop. C. Just $14.2 million, or less than 2% of the funds, will go toward boosting services for residents in existing supportive housing hotels and apartments.

“The public wants people off the streets, and (politicians) are getting hammered with, ‘Solve this problem now,’ ” said Margot Kushel, the UCSF researcher. Better conditions for those housed years ago are “not what the public is really clamoring for.”

For the thousands of San Francisco residents living in poorly funded, staffed and maintained hotels, little will change — even though improving these SROs can be a matter of life or death.

In 2011, Joel Yates moved into the Hamlin Hotel in the Tenderloin. Maintenance of the building was adequate, he said, but his small room — comprising nothing more than a sink, a bed and a window that looked onto a wall — reminded him of a jail cell.

Yates had recently left a house dedicated to clean and sober living, and was early in his recovery. When he bumped into a neighbor on his floor smoking crack cocaine, Yates relapsed. (At least two people have suffered fatal drug overdoses at the Hamlin in recent years, records show.) He stopped eating and sleeping, lost his job as a maintenance worker and hoarded scavenged items to sell.

One day in 2016, as Yates was trying to sleep in his room, he struggled to breathe. At San Francisco General Hospital, he was diagnosed with cardiac distress, a result of kidney failure. If left untreated, he probably would have died.

When Yates returned to the Hamlin after weeks in a hospital bed, he said, he learned he had been evicted. The property manager accused Yates of failing to keep his room in “a clean, decent, sanitary, and safe condition,” court records show.

For six months, he slept in an emergency shelter. During this time, because of his life-threatening illness, the city offered him rooms in several SROs. But he turned them all down.

Recently, the Hamlin’s owner, Chinatown Community Development Corp., completed a major renovation of the building, adding a new elevator, community spaces and kitchens, and updating the rooms.

But at that time, Yates explained, he preferred to be homeless rather than live somewhere like the Hamlin again.

“I knew what the conditions were,” Yates said. “I needed to heal. I needed to recover. And I needed a place where I wasn’t going to feel trapped.”

Then, in early 2017, Yates accepted a room at the Kelly Cullen Community. His kidney disease had made him eligible for the hotel, which housed homeless people with acute medical conditions. He asked his new case manager for a unit with a kitchen so he could eat healthy, and he asked to be able to see the sun.

Yates thrived after moving into Kelly Cullen. He stayed sober and took care of his health. He enrolled in a career development class and is now a community health worker. He joined a performing arts group with other SRO residents. He reconnected with family.

“God has blessed me,” he said of his placement at Kelly Cullen.

The only problem, as far as he can tell, is that he had to almost die to get there.

Joaquin Palomino and Trisha Thadani are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: jpalomino@sfchronicle.com, tthadani@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @joaquinpalomino, @TrishaThadani

PODCAST: Hear reporters Joaquin Palomino and Trisha Thadani discuss their SRO investigation with host Cecilia Lei on the Fifth & Mission podcast at sfchronicle.com/fifth.