Middle class struggles to buy homes in Bay Area

By Lauren Hepler

It may pay more to work in the Bay Area compared with other regions of the U.S., but for middle-class residents, new research shows it’s a trade-off that increasingly means giving up buying a home.

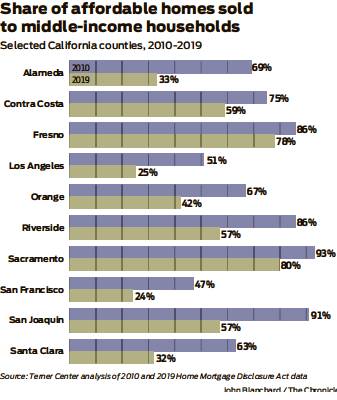

Households earning around $80,000 to $165,000 qualify as “middle income” here, depending on the location and family size, compared with a national median income of $67,521. Even before pandemic bidding wars, it wasn’t enough to keep up with soaring home prices: Just 24% of homes sold in 2019 in San Francisco fell into price brackets that middle-class buyers could afford, according to a report released Monday by UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

Those in the thick of the region’s frenzied housing market say the barrier to entry has only gotten higher since the coronavirus upended daily life.

Prospective buyers are borrowing cash or moving farther away. Residents who already own homes are going to extremes to keep them. Those shut out of homeownership are spending more on rent, widening inequality and increasing fears about essential workers like teachers being priced out for good.

“To be able to qualify for any of these houses anywhere in the Bay Area, you have to have an average annual income of $235,000,” said Tim Yee, a real estate broker and president of RE/MAX Gold Bay Area. “It’s crazy, and for first-time home buyers, it’s extraordinarily hard unless they have very wealthy parents.”

In San Francisco, as recently as 2010, 47% of homes for sale were affordable to middle-class buyers — defined as those making 80% to 120% of the local median income — according to the report. Alameda and Santa Clara counties saw even steeper declines in affordable home sales, from almost 70% and 63% of homes sold in 2010, respectively, to just over 30% in 2019.

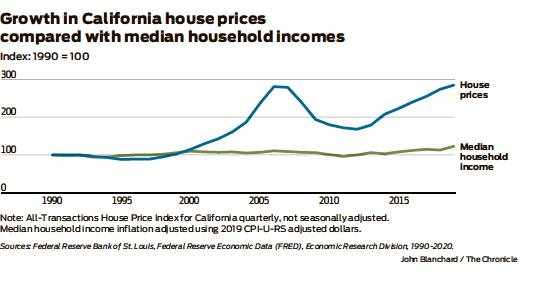

Though prices have been rising for decades, economists like Stanford University’s Mark Duggan said “little breaking points” are getting harder to ignore. They range from anecdotes about truck drivers and teachers leaving the state to worker shortages at local institutions like his kids’ own Palo Alto schools.

“My school district couldn’t get bus drivers, so all the parents have to cobble together carpools,” said Duggan, the director of the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. “My view as an economist would just be pay the bus drivers a lot more.”

The pay problem

During the Bay Area’s boom years from 1940 to 1960, the average home sold for around $15,000, equivalent to about $140,000 today, according to the Terner Center report. Rents averaged around $80 a month, or roughly $760 in today’s dollars. Housing costs were largely in line with incomes, allowing factory workers, teachers, nurses and line cooks to spend less than a third of their incomes on housing.

With median home prices hovering around $1 million as of 2019, the report found 39% of middle-class Bay Area homeowners spend more than 30% of their income on housing.

For renters, the cost burden is even higher, showing how being shut out of homeownership can drain savings and reinforce wealth gaps. About 49% of middle-class Bay Area renters spent a higher portion of their earnings on housing in 2019.

“The prospects are dwindling as costs continue to rise and incomes don’t go up,” said Terner Center policy director David Garcia, who has seen the pressure push more Bay Area workers to areas like his hometown of Stockton. “It’s not just kind of a coastal area problem,” he said. “These affordability issues are increasingly kind of seeping into more suburban and rural portions of the state.”

Across California, about 52% percent of middle-income residents owned their home as of 2019, down from more than 59% in 2000. The numbers also mask stark racial divides. Almost two-thirds of Black middle-class households in California rent their homes, compared with 37% of white households, which the report attributes to factors including lower average pay, discrimination in home lending and the legacy of racist housing laws.

Income aside, the report highlights a severe lack of new homes and disproportionately expensive housing in areas that are building. As it stands, California ranks No. 49 for the fewest homes per capita, with 358 existing homes per 1,000 people, compared with the national average of 419 homes.

That imbalance is increasing pressure on lawmakers to consider more radical reforms. In addition to recent moves away from single-family zoning and increasing penalties for communities that refuse to build new housing, state Assembly Member Alex Lee, D-Milpitas, also sees an opportunity to increase support for “social housing” concepts already popular overseas in places like Vienna and Singapore.

The Bay Area could increase housing for workers, students and others, he says, by repurposing public infrastructure like parking lots and shuttered schools and turning the sites into mixed-income housing. Under his bill, AB2053, a new California Housing Authority would both buy existing housing and build homes where higher-earning residents’ payments would help subsidize lower rents for neighbors.

“I hope social housing would give a competitive option,” Lee said. “All the options are pretty bad right now.”

Stay or go?

In the sweltering heat and paralyzing uncertainty of August 2020, Sharon Dolan had a big decision to make.

Her now-ex-husband had moved out of the Oakland fixer-upper they bought in 2008. So the longtime nonprofit and theater executive had to decide if she was going to find a way to keep the house, downsize or leave the Bay Area like many other artists she knows.

With wildfire smoke choking out the sun, she got in her car and drove. First to a friend’s in western Massachusetts, then down the Atlantic coast, then into the West’s vast natural parks.

“I was kind of thinking about, ‘Where would I live if I could live anywhere?’ ” Dolan recalled. “The conclusion I came to was I’m happy in the Bay Area.”

With the help of a retired real estate agent, a plan emerged to refinance the house, buy out her ex and install a kitchenette to rent out the upstairs. Dolan said she was fortunate to find a good housemate.

The $2,500-a-month mortgage, plus property taxes and other ownership costs, would have been out of reach on Dolan’s pay alone, which in recent years has averaged slightly above Oakland’s $80,000 median household income.

“I don’t know if I’m going to be able to stay in the Bay Area or ever retire,” said Dolan, 62. “But I have some equity.”

Entire online subcultures exist for other Bay Area residents interested in various forms of “house hacking” to pay high mortgages or keep up an inherited family home. Other corners of Facebook and Reddit are populated by fed-up families mapping out exits to lower-cost states, plus all manner of hustlers looking to break into the market by taking out risky loans or targeting distressed properties.

There’s also the option of leaving. Though as a former Bay Area resident himself, Davis Realtor Greg Stidham knows it can be difficult to give up big coastal cities for more affordable inland areas.

Some first-time buyers are swayed, he said, by the chance to own the kind of three-bed, two-bath home where they can raise a family. He also sees transplants looking to cash out on Bay Area homes bought long ago, driving up the local market, but also offering a chance to put down roots before weddings, graduations, retirements and other milestones.

“All those life events are still happening,” he said, “and this market doesn’t care.”

Lauren Hepler (she/her) is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: lauren.hepler@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @LAHepler