OPEN FORUM On Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Don’t gloss over risk from methane

By Sam Abernethy

Energy-related carbon emissions rose to their highest level in history last year, according to new analysis from the International Energy Agency. The news comes just weeks after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, issued a report warning that global warming is happening so rapidly that humanity may no longer be able to adapt.

Since carbon dioxide accounts for the majority of global greenhouse gas emissions, it’s understandable that curbing it is the first priority for climate change activists. But there’s another dangerous greenhouse gas that most people don’t fully appreciate: methane.

Although the second-leading contributor to global emissions, methane is the more potent greenhouse gas because it has a higher ability to trap heat in the atmosphere. So why has it been largely overlooked? Bad math.

Mainly due to precedent set by early IPCC reports, climate experts usually measure global warming potential — the heat absorbed by any greenhouse gas in the atmosphere — over a 100-year period. That makes sense for carbon, which stays in the atmosphere for centuries. But methane has a lifetime of only around a decade, so some scientists have argued that we should measure its impact over a shorter time frame of 20 years instead.

Either way, these time frames are arbitrary — chosen largely because people are comfortable thinking in decades and centuries. There’s no real scientific justification for them. However, for the first time, my colleague, Stanford professor Rob Jackson, and I have calculated methane’s impact in a way that aligns with the goals of the Paris Agreement to keep global warming under 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably to 1½ degrees.

In our research published last month, we show that future climate scenarios in which temperature peaks at 1½ degrees Celsius occur, on average, around 2046 — 24 years from now. Evaluated over that 24-year time frame, methane is 75-times worse than carbon dioxide at limiting global warming to 1½ degrees.

In practical terms, this has huge implications for climate policy. The Biden administration has committed to implementing policies that would put the U.S. on a path to limiting warming to 1½ degrees, but our study suggests the Environmental Protection Agency is relying on a woefully inadequate methane valuation — three times too low — to most efficiently meet this target.

By undervaluing methane’s impact on global warming, the largest sources of methane pollution from human activity — such as the liquefied natural gas and dairy industries — appear less detrimental to the climate than they actually are. This undervaluation also disincentivizes methane emission reductions or removal.

In truth, the time frames used to value greenhouse gas warming potentials should change over time to reflect current emissions and policies. Current national climate pledges have us on a warming path that would peak at 2.7 degrees in approximately 100 years — valuing methane with a century-long time frame only makes sense if we are resigned to such a devastating future. As stronger climate policy is pledged and implemented, the time frames used to calculate emission metrics should be adjusted in lockstep to most efficiently meet our climate goals.

Correctly valuing the impact of greenhouse gases is a necessary step toward effectively combating global warming, but it’s only one piece of the puzzle. The far larger task is increasing the speed and magnitude of climate action. It is imperative that we rapidly scale down carbon dioxide emissions to net zero in order to stabilize temperatures. Methane reductions are an important complement to these efforts, not a replacement.

Fortunately, last year saw major strides in national and global commitments to eliminate methane pollution. In November, the U.S. and the European Union, along with many of the world’s largest emitters, committed to a Global Methane Pledge to reduce emissions by 30% by 2030 from 2020 levels. In the U.S., the EPA recently proposed new rules that would slash 41 million tons of methane emissions from oil and gas extraction by 2035.

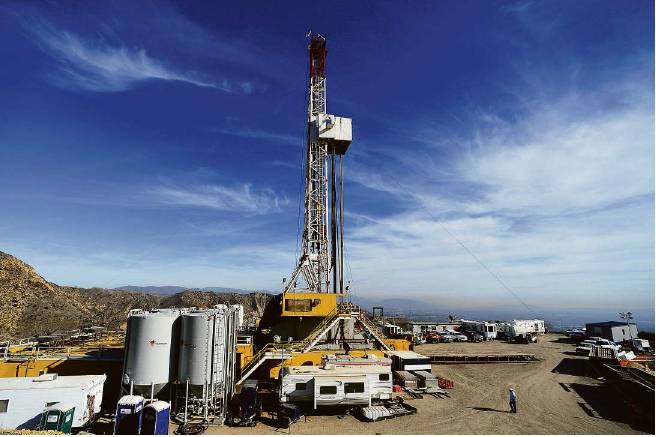

While encouraging, the EPA’s policy has long been to wait on the notoriously slow-moving IPCC to update its emission metrics, meaning the U.S. is stuck using the 100-year time frame until at least 2024. But as a leader in fighting climate change, California doesn’t have to wait. California’s Air Resources Board could be an early adopter of the 24-year time frame and align its valuation of methane with the 1½-degree goal. Such a change would help prioritize the cleanup of California’s sizable methane problem: Los Angeles was home to the largest methane leak in U.S. history, while recent satellite imagery has shown many methane super-emitters scattered throughout the state.

The droughts, heatwaves and wildfires that are now a regular part of California life are just a preview of the devastation we’ll face if we don’t move quickly to curtail greenhouse gas emissions. Efforts to reduce methane must be lauded and redoubled — and valued correctly for the benefits they will bring — to slow the “dangerously fast” rise of atmospheric methane that is contributing to climate extremes. Methane reductions would have substantial benefits in the short-term, slowing the pace of global warming relatively quickly.

The IPCC, along with national and regional governments, should base their policies on time frames that bring emission metrics into alignment with the goal of keeping warming under 1½- degrees Celsius. We must keep that target in sight to have any hope of hitting it.

Sam Abernethy is a fourth-year applied physics doctoral candidate at Stanford University who studies the impacts of methane removal and the technologies to make it feasible.