Freeway shootings, saddening toll rising

Incidents have tripled in 3 years; perplexed police make very few arrests

By Rachel Swan

The year had barely started when a major Bay Area freeway saw its first burst of gunfire, right at the onset of rush hour.

On the afternoon of Jan. 4, a bullet fired by a yet-unknown shooter hit Alameda County sheriff’s recruit David Nguyen as he drove his Toyota Prius west on Interstate 580 toward the Bay Bridge toll plaza. Nguyen apparently slumped over the wheel and crashed his car into a guardrail, becoming one of the latest victims of a surge in highway violence.

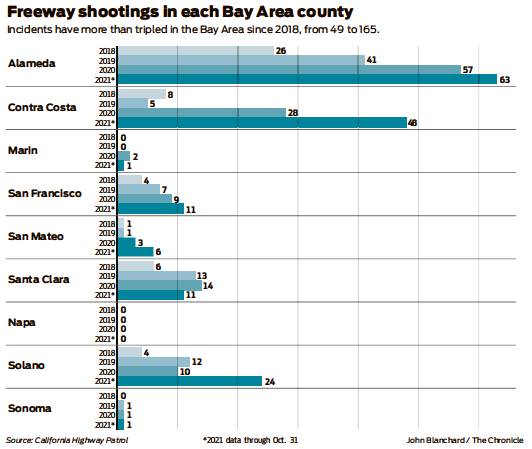

Over the past three years, shootings have more than tripled on the arterials that knit the region together — from 49 Bay Area freeway shootings in 2018, to 165 through October last year, according to the California Highway Patrol in response to a public records request from The Chronicle. Limited available records also show a spike in deaths — from two fatal freeway shootings for the whole Bay Area in 2018, to six gun deaths on Oakland freeways alone in 2021.

Among the lives claimed by these attacks were a toddler strapped in his car seat, teenagers packed into a party bus, and Amani Morris, a mother on her way to a job orientation. Their stories reflect the human toll of a trend that presents galling challenges for law enforcement.

“It just angers me so much,” said Alicia Benton, Morris’ mother. The two were FaceTiming minutes before gunfire killed Morris on I-80 near the Bay Bridge on the morning of Nov. 18.

The 29-year-old Antioch mother was riding in an SUV to a training for her new job at a child care service. Morris’ fiance drove while her two sons, ages 5 and 3, sat in the back seat. Police have made no arrests in the case.

Each roadside crime scene is perplexing, law enforcement officials say: By the time officers arrive, the perpetrator may be long gone, the bullet casings scattered far away, the witnesses elusive.

While officials hope the escalating bloodshed of recent years doesn’t carry into 2022, the I-580 shooting served as a terrifying portent.

Sgt. Raul Gonzalez of the California Highway Patrol attributed many shootings to “road rage incidents or targeted gang violence,” and said the chance of a bystander being shot is “extremely rare.” Nonetheless, several recent, high-profile incidents appear to be innocent victims caught in the crossfire.

Records from the California Highway Patrol illuminate the depth of the quandary for officers, who make arrests in only a portion of cases. For example, the agency’s Golden Gate division — which covers the Bay Area — documented 49 shootings in 2018, which led to two homicides, 23 injuries and eight arrests.

The largest share of shootings took place in Alameda County, where the CHP said it received reports of 74 incidents by the end of 2021. Highway Patrol officials did not provide arrest numbers for that year.

Interstates 580 and 880 in Oakland saw the most shootings of any Bay Area freeway in 2018 and 2019, the years for which such data was available.

With most of these cases unsolved, law enforcement and criminologists are left to speculate about motives. UC Berkeley criminal law professor Jonathan Simon said that “only two criminal scenarios come to mind” in freeway shootings: road rage assaults or calculated attacks against a motorist who the perpetrator already knew. Such encounters could be aggravated by the growing number of people who are armed, Simon said.

Stanford University law professor Robert Weisberg ascribed the vast increase in shootings to “a tragic exacerbation of gang disputes” made more volatile by the proliferation of guns. He noted that freeways are sites of repeat behaviors, where many drivers cross the same stretch of road at the same time each day. A person wanting to ambush a driver could analyze that person’s movements and then follow them.

“Then it’s just a relocation of street shootings, in some ways,” Weisberg said, adding that retaliatory shootings beget more retaliatory shootings, a ruthless cycle of self-reinforcement.

Oakland has been a perpetual hot spot for freeway shootings, even in 2018, a year in which the city’s homicide rate went down. Almost half of the 20 freeway incidents recorded that year occurred on I-580, which stretches east from the MacArthur Maze, bifurcating the city’s hills from its flatlands.

Yet gun violence also plagues the region’s more rural highways, including Highway 4, which branches from I-80 into the tawny landscape of Contra Costa County, toward the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta.

The alarming number of shootings along this route began worrying prosecutor Mary Knox in 2015, when she ran the Community Violence Reduction Unit in the Contra Costa District Attorney’s Office. Around that time, Knox reached out to private companies to develop a “freeway security network,” an intricate system of cameras, license plate readers and ShotSpotter gun detection devices used to pinpoint the exact times and locations of shootings and alert officers as soon as a gun was fired. The camera feed is so powerful, Knox said, it can capture the muzzle flashes from suspects’ cars.

In 2017, Contra Costa County law enforcement agencies secured $3.5 million from then-state Transportation Secretary Brian Kelley to turn the security network into a three-year pilot program, installing a wireless backbone from I-80 in Richmond to Highway 4 in Antioch to feed data into a command center. By 2019 it was fully operating and serving as a deterrent, Knox believes, though data shows that shootings more than quintupled in Contra Costa County the following year. Knox currently is running for district attorney in Contra Costa County.

Caltrans extended the freeway security network pilot program last June, and officials hoped to develop technology that would bolster investigations of organized retail theft caravans. But critics, including Oakland Privacy Advisory Commission Chair Brian Hofer, question whether the technology has an impact.

Hofer sued Contra Costa County in 2019, alleging that sheriff’s deputies pulled guns and illegally searched his car following a traffic stop on I-80, when a license plate reader identified Hofer’s rental car as stolen. Hofer settled with the sheriff for almost $50,000 last year, though the experience led him to conclude that freeway surveillance technology is intrusive, prone to errors and could lead to racial profiling.

“I haven’t seen sufficient data to believe that it’s an effective solution,” he said. “It clearly doesn’t have a deterrence effect because there’s been an increase in shootings.”

Other counties seek to replicate some of the efforts of Contra Costa County, despite misgivings from privacy advocates. In December, Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf wrote to Gov. Gavin Newsom, asking for more assistance from the Highway Patrol on arterial streets, as well as license plate readers on freeway on- and off-ramps.

For Carl Chan, a prominent public safety advocate and president of the Oakland Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, surveillance equipment on freeway ramps is just the beginning. He wants to see the same technology deployed at busy city intersections.

Chan is close to the family of Jasper Wu, the 23-month-old toddler who was killed in November while sitting in his family’s car, traveling south along I-880 in Oakland. Police say a stray bullet flew into the car from the opposite side of the freeway.

At this point, the family is trying to move away from the home they rent in Fremont, Chan said, because everything reminds them of Jasper. The wounds reopen each time they hear about another freeway shooting — and the violence shows no sign of abating.

A week before Wu’s death, on Oct. 27, 27-year-old Monnie Price Jr. was shot and killed as he drove onto the I-580 on-ramp at 98th Avenue. His father, Rev. Ramon Price Sr., works at a funeral home in Oakland and has now lost two sons to gun violence. When he got a call from the coroner about Monnie, Price said he recognized the number immediately and began weeping.

Within nine days, a gunshot had struck and killed Wu, and on Nov. 18 an unknown assailant slayed Morris, the devoted mother who was giddy about her new job, Benton said. Wracked with grief, Benton prepared to raise her two grandsons at her home in Georgia.

Then, four days into the new year, Nguyen was killed in the thick of afternoon traffic.

“This has been a whirlwind, and it’s not over,” Benton said. “Because I’m coming to get two little people at the end of the month — I’m going to raise my grandkids now.”

Rachel Swan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: rswan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @rachelswan