FIRST OF TWO PARTS

BLAST ZONE

Hill Country quarries dump sediment into waterways, send dust into neighborhoods — with little regulation or penalties

By BRIAN CHASNOFF | STAFF WRITER

Flat Creek had always been translucent, flowing clear and cold through Kathleen Wilson’s 15-acre spread in the Texas Hill Country.

Then something changed. The dust was the first sign.

“That was really the first noticeable thing, was the whole surface was covered with dust,” said Wilson, 63, who runs an eco-friendly bed and breakfast on the Blanco County property. “You’d stick your hand in and it would, like, stick to you.”

Soon, the water was choked with “mucky, nasty stuff,” Wilson said. “It was never dirty before. This is a spring-fed creek.”

The source of the problem: a limestone and caliche quarry 4 miles south of Wilson’s land, near the headwaters of the creek.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has tried and failed repeatedly to stop the quarry from polluting the water. Since the quarry opened in 2016, the environmental agency has cited its operator three times for the same violation: allowing sediment and rock to spill from its property, fouling the creek.

Twice, the quarry, known as the West Henly Site, said it had fixed the problem. Twice, the result was another spill. The TCEQ could have enforced its rules with a financial penalty but never sought to do so.

The creek has never been the same.

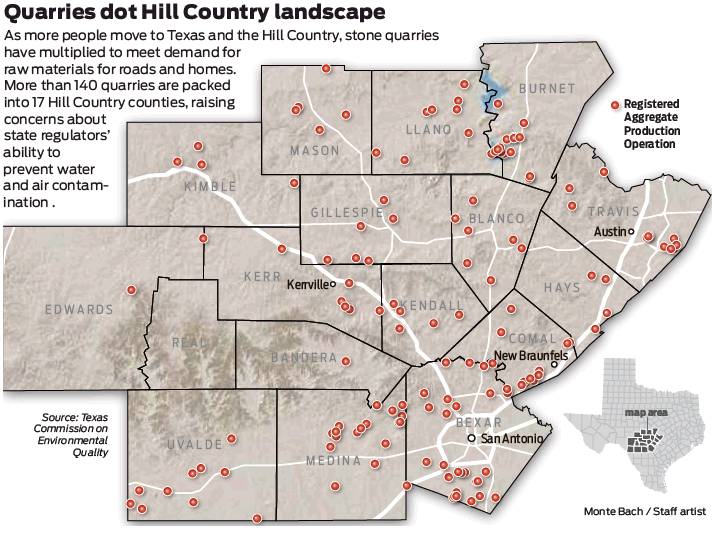

The pattern of repeat violations has played out again and again in the Hill Country, a treasured landscape of rolling hills, creeks, rivers, natural springs and striking rock formations across 17 counties.

Hill Country quarries have dumped sediment into waterways and sent plumes of potentially hazardous dust into neighborhoods, a San Antonio Express-News investigation found.

The violations have spoiled pristine waterways and threatened the Edwards Aquifer, the region’s prime source of drinking water. Releases of fine particulate matter have coated cars and homes.

TCEQ enforcement actions can’t be relied on to halt problems. In at least nine documented cases in the Hill Country, the agency has failed to stop repeated infractions as earthen barriers meant to protect rivers have crumbled, dust has blanketed homes and workers have ignored rules put in place to prevent contamination of the aquifer.

Only in rare cases has the state levied financial penalties.

Inspections are infrequent. In the absence of complaints, the TCEQ will inspect a site once every two years in its first six years of operation, and just once every three years after that.

The public is left blind to the scope of problems.

If citizens check whether a quarry has violated state rules, they’ll often find nothing in TCEQ records — even if the quarry is a chronic offender. Under state law, the TCEQ removes any notice of a violation from a quarry’s five-year compliance history after a year has passed, leaving behind a spotless document even for sites with the spottiest records.

Quarries are authorized to discharge hazardous dust into the air as their operators blast, dig, move, crush and stockpile exposed rock.

To obtain an air permit in Texas, a quarry is required only to predict how much particulate matter a piece of equipment, such as a rock-crushing machine, will emit, and promise to control the dust and comply with federal air quality standards.

These calculations don’t account for other sources of air pollution on-site, such as the dust produced by blasting and trucks hauling rocks.

If a quarry says on a permit application that it will meet all required conditions, the TCEQ must approve the permit. In the past decade, the agency has denied just nine out of 4,523 applications for equipment at quarries.

The TCEQ doesn’t actually monitor air quality at quarries. The agency operates 76 regional monitoring stations, required by federal law, that measure particulate matter. They’re scattered across the state. The devices are not meant to measure emissions from any particular source. As a result, the TCEQ can’t document how much harmful material was released when dust from a quarry coats nearby homes.

‘Growing like crazy’

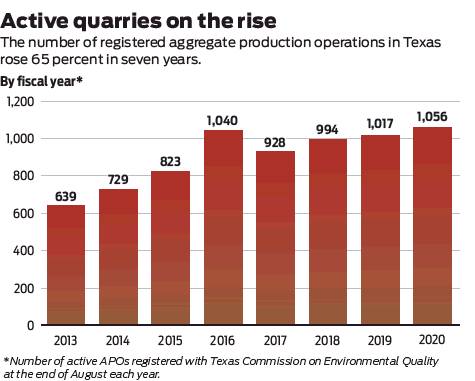

There are more than 1,000 active stone quarries across Texas. The number registered with the state has risen sharply in the last seven years, from 639 in 2013 to 1,056 in 2020.

Their operators clear away trees and blast holes in the earth to dig up and crush rock for the construction of new roads and homes, all to keep up with booming growth as an average of 1,000 people move to Texas every day.

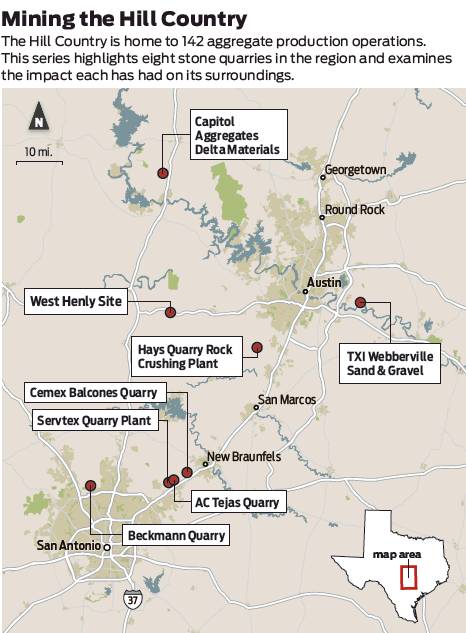

The $10 billion industry thrives in the Hill Country, where142 quarries mine the region for its rich store of limestone and other resources. Bexar County has the most: 27.

Working night and day, the sites — known as aggregate production operations, or APOs — churn out towering mounds of granite, gravel, soil, sand, caliche and limestone piled across vast, man-made canyons that can grow to thousands of acres.

Some quarries operate next to creeks and rivers because that’s where the resource lies. The Hill Country is the most lucrative source in the state for limestone, a key ingredient in cement.

“There’s only a certain amount of rock in Texas, and it’s all in one location in the state where we can get good rock for these projects,” said Josh Leftwich, president of the Texas Aggregates and Concrete Association (TACA), an industry group.

“Texas in general is just growing like crazy,” he added. “The amount of infrastructure projects going on in the state has just spurred this industry a lot.”

Many quarries use hundreds of millions of gallons of water a year to control dust and wash rocks. In 2016, Martin Marietta Inc. used 1.3 billion gallons of water at its Beckmann Quarry, a 1,640-acre site in San Antonio next to Eisenhower Park, according to data provided by the Texas Water Development Board.

That’s more than twice as much water as was consumed in 2020 by all the H-E-B supermarkets, warehouses and other facilities served by the San Antonio Water System, according to the utility’s annual financial report.

Some quarries recycle water, but that’s not required.

The state does require quarries to capture and treat stormwater before releasing it into waterways. But the sites are allowed to construct water control structures any way they see fit, often without rigorous engineering, according to a 2020 report by a Texas House committee that studied APOs.

The TCEQ asserts that its permitting and enforcement rules are enough to protect human health and the environment. The agency said that in 2013, its inspectors documented at least one violation at 39 percent of the quarries they investigated, and that by 2020, the figure was down to 17 percent.

Over the same period, the TCEQ said the number of investigations increased from 558 per year to 1,568, mainly because there were more quarries. In addition, the Legislature in 2019 required more frequent inspections — once every two years, rather than once every three, during a quarry’s first six years of operation.

When inspectors find a violation, the TCEQ requires the operator to “undertake all corrective action necessary to resolve” it, the agency said in a statement.

‘Scoured and eroded’

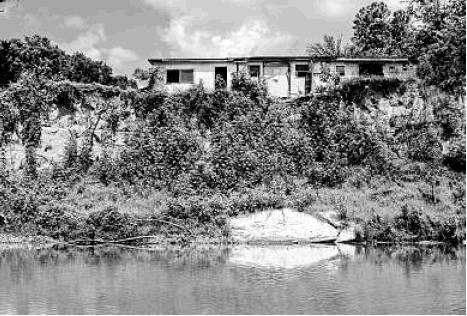

On a summer afternoon in Garfield, 17 miles east of Austin, Matthew Macon stood at his property line — right where it plunged 40 feet into the Colorado River.

Just a few years ago, Macon, his wife and their children had a backyard. Now, his back porch lay broken in the muddy water below. Their house, gutted and wrecked by floodwaters, clings to the edge of a cliff.

Macon bought the forested lot in 2005.

“I had land,” said Macon, 46. “I had a nice beach down there. I had a boat ramp that went to the water. That was really nice. You could walk down to the end and go sit down there, put your feet in the water, drink a beer, watch the sunset. In one year, we lost 90 feet — 2015 to 2016.”

Across the river from Macon’s property lies what is now known as the TXI Webberville Sand & Gravel quarry, which opened in 2002. Earthen berms separating the quarry’s mining pits from the river have failed repeatedly, allowing sediment-laden water to spill into the Colorado when it rains, TCEQ records show.

The problem has persisted for years — not just at the Webberville site, but at stone quarries across the state.

The TCEQ has long known about it.

In 2004, the agency embarked on its Clear Streams Initiative, a statewide effort spurred by complaints about the harmful impact of stone quarries on the Brazos watershed, which extends from Lubbock to the Gulf Coast near Houston.

The TCEQ found that “certain quarry operations had encroached close to the Brazos River or its tributaries and significant sedimentation from uncontrolled storm water runoff had resulted in increased turbidity and negative effects to the streambeds and watercourses from sediment loading,” according to a 2006 TCEQ report to the Legislature.

“At sites that appeared to be having the greatest impact, quarry activity was being conducted very near the river,” the report said.

In 2005, the year Macon moved into his house overlooking the Colorado, the TCEQ received complaints that the Webberville quarry was pumping water from a mining pit, and that its berms had altered the course of the river and caused erosion on the opposite bank.

An investigator found no violations and concluded that “natural river system dynamics” had caused the erosion but also noted that “river flooding” had damaged the quarry’s berms, requiring repairs.

In 2007, the TCEQ received another complaint that the quarry was pumping “muddy water” into the river, again causing the opposite bank to erode. This time, a TCEQ investigator found breaches in three berms at the site, as well as a “side channel” leading from a mining pit to the river.

“Water flowing from the pit into the river was turbid and a plume of sediment laden water was noted entering the river,” the investigator wrote.

The TCEQ also found that the quarry was pumping water from a mining pit through a pipe and into a creek that fed into the river.

The damage to the waterway was visible.

“The edge of the bank was scoured and eroded due to the high velocity of water exiting the pipe,” the investigator wrote.

Nonetheless, the TCEQ again concluded in 2007 that “natural river system dynamics” had caused the erosion. Development upstream — roads, parking lots and other impervious cover — had increased the volume of runoff, contributing to the problem, the agency said.

Still, the TCEQ cited the quarry for the unauthorized discharges and told it to repair the berms and stop pumping water into the creek. Later that year, the site’s operator told the TCEQ it had resolved the issues.

Martin Marietta Inc., a nationwide supplier of building materials, took over the quarry in 2014.

Another TCEQ investigation in 2016 found that berms separating old mining pits from the river “were not fully intact,” causing stormwater in the pits to flood the river repeatedly from 2009 to 2016.

Investigators that year could not inspect the pits because they were “inundated with water.” A quarry official could not provide the TCEQ any record of steps taken to prevent stormwater pollution at the site. A severe flood in October 2015 had damaged the documents “beyond repair,” he told the agency.

The same flood had pushed the Colorado River over the opposite riverbank and left a foot of mud inside Macon’s home. By 2016, he had lost his backyard to the water below.

That year, the quarry told the TCEQ it was not inspecting its berms due to “high water and other safety considerations” — a violation of state rules.

The TCEQ cited the quarry for failing to put into effect a stormwater pollution prevention plan and requested that it document how it would do so. In an email that year, a quarry representative told the TCEQ that the effort was “currently in process.”

The TCEQ could have elevated the issue to a notice of enforcement, a compliance tool intended for “serious or continuing violations.” A notice of enforcement authorizes the TCEQ to seek penalties to deter future violations, either through administrative action or a civil lawsuit. But no such action was taken against the Webber-ville site, according to its compliance history report.

Martin Marietta declined to comment for this article.

Despite its 2016 violation, the quarry has a perfect TCEQ compliance history from September 2015 to August 2020 — at least officially.

Anyone who requests a report for the Webberville quarry — someone thinking about buying property in the area, for instance — would see an “N/A” under the section reserved for “written notices of violation.”

‘Pits fail repeatedly’

An Express-News reporter and photographer visited the site this summer to assess the state of the river and the quarry. They found the same problems.

The pair paddled a canoe from the Colorado into abandoned mining pits, passing through a breach in a berm where rocks had toppled over and left an open channel to the river.

Such breaches upset a river’s natural “sediment budget” — the amount of sediment in the water — and can cause erosion and increased flooding, said Bill Dupre, a professor of geology and sedimentology at the University of Houston.

Breaches also cause rivers to change course, he said.

“When you change the sediment budget, you change the equilibrium of the river,” Dupre said. “Rivers erode naturally, but if you find that it’s increasing and suddenly you lose a bridge or a house, then it’s no longer just an academic question.”

Dupre is an expert witness for Texans for Responsible Aggregate Mining, a group that advocates for stricter regulation of quarries. He and others have pushed to prohibit quarries from excavating within 200 feet of a river.

“Breaches, once formed, can stay open for years,” Dupre said. “They will not fix it unless they’re caught. We need to be thinking about how we anticipate the future location of the river when we start siting these pits. And the reason we do that is these pits fail repeatedly.”

Carson Conklin, a Travis County firefighter, said the contours of the river around the Webberville quarry are constantly changing. Conklin has led fishing trips on the river for six years. He often steers clients into the quarry’s abandoned mining pits, where white bass are abundant.

The sediment “pretty much rerouted how that water is coming out of that quarry,” he said. “There is just a lot of dirty water now spilling into the river.

“I’ve had to take multiple routes to get into those quarries because they change all the time,” he added. “Every few weeks it looks a little different. There are banks that have smoothed out completely, or little islands that have come about and disappear within a few weeks. It’s all just sediment moving around.”

The quarry is “ruining the color of the river,” Conklin added.

To Macon, the river today is unrecognizable.

Standing beside his abandoned home on the edge of his property, he pointed to where the wide, muddy water snaked abruptly west. Fifteen years earlier, the river ran straight in that area — a past captured by historical Google Earth imagery.

“When I bought the land, the river was straight along here,” Macon said. “The river had a lot less of this ziggy-zaggy back and forth, this extreme back and forth.”

Macon since has built a new house a little farther back from the crumbling bank. He said he has never considered suing the quarry for the loss of his land.

“Their lawyers are better than my lawyers,” he said. “It’s the golden rule. They’ve got the gold.”

‘They use fear’

In the last two sessions of the Legislature, a bipartisan group of lawmakers has tried to enact more stringent rules for quarries. But the concrete and aggregates industry has smothered the initiative twice.

The inertia is galling to state Rep. Terry Wilson, a retired Army colonel and conservative Republican from Marble Falls in Burnet County. Last year, Wilson served as chair of a House study committee that published a 65-page report on aggregate production operations.

“I was hoping that we would identify the best practices,” Wilson said. “And by saying, ‘Hey, if this is the industry’s best practices, then why don’t we make that the threshold in terms of the standard?’ ”

Burnet County is home to 16 active stone quarries. The TCEQ cited one of them, Capitol Aggregates Delta Materials, in March 2017 for failing to implement a stormwater pollution prevention plan. The agency also found the quarry needed to extend a berm to prevent pollution.

Eight months later, not only had the berm not been extended, it had collapsed. Sediment from the site — quarried dolomite — had spilled into a tributary of Backbone Creek, and other berms at the quarry had failed due to “poor design, installation and maintenance,” an investigation report said.

Capitol Aggregates, which is headquartered in San Antonio, later told the TCEQ it had repaired the berms, and the compliance case was closed.

The company’s president, Greg Hale, sat on Wilson’s study committee, along with David Perkins, a former president of the industry group TACA who is now vice president of government affairs for Lehigh Hanson Inc., a producer of construction materials based in Germany.

Both Hale and Perkins refused to sign the committee’s report.

In a letter to Wilson, Hale asserted that the committee had ignored testimony from “industry stakeholders and experts” and had not adequately considered how its recommendations could “greatly hinder economic development.” He also said the recommendations were unsupported by “relevant evidence and data.”

Leftwich said industry officials “just didn’t have the time to really thoroughly comment and review things in a timely manner.”

A bill written by Wilson — and co-sponsored by more than 100 lawmakers, Democrats and Republicans — would have incorporated a slew of the report’s recommendations.

Among other measures, House Bill 1912 would have required quarries to ensure the land they mine will be “safe and useful” after operations cease, in part by re-vegetating barren areas to control erosion.

At present, such rules apply only to the John Graves Scenic River-way, a sinuous, 19-mile stretch of the Brazos River west of Fort Worth.

At a hearing on the bill in April, the House environmental regulation committee heard from Mark Friesenhahn, a pecan farmer whose Comal County property was damaged in June 2020 when a retention pond at a limestone quarry spilled mining waste onto his orchard.

“Farmers have a key mission, and that is this: At the end, we strive to leave the land better than we found it,” Friesenhahn told the committee. “It’s pretty simple. You till it, you fertilize it, you prevent erosion and all those things to bring it into good shape. We would think that APOs would be required to do pretty much the same kind of thing.”

Also testifying that day — against Wilson’s bill — was Leftwich.

“I think the rules and requirements that are in place are sufficient and protective of the environment,” he said.

Leftwich told the committee that the TCEQ operates “130” regional air-monitoring stations across the state; the actual number is 76.

After the hearing, House Speaker Dade Phelan held a closed-door meeting of stakeholders, including Wilson, Leftwich and Republicans on the committee, to find areas of compromise. Beyond agreeing to answer more questions at public hearings, TACA wouldn’t budge.

“We couldn’t even get the lobby to agree to the simple things that they’re already doing: acceleration, deceleration lanes for trucks. Nothing. The answer is nothing,” Wilson recalled, venting over a slice of German chocolate pie at Marble Falls’ storied Bluebonnet Cafe.

Not far from where he sat, workers once mined red granite to build the Texas Capitol in the 19th century.

“I mean, look, I got it,” Wilson said. “We were a mining community back then. Our state Capitol is from right here. But when I look at the greed and how we’re not concerned that as we’re developing and providing for this growth, which we should be, that we shouldn’t be protecting our rivers and streams — that’s ludicrous.”

Wilson’s bill never made it out of the committee, a failure he laid at the feet of his fellow Republicans.

“It was enough for the Democrats,” he said. “And that’s where I’d say to my Republican members that, you know, taking care of our people, of our resources, is conservative. I don’t know where in the hell we went wrong where we have labeled conservative to mean not protecting our environment.”

Wilson said the APO lobby is so influential in the Statehouse that “you’re literally asking them, ‘Can I pass this legislation?’ ”

He added: “When you bring a bill — and this is in both chambers — to the committees, the first thing that they do is send it to the industry on whether it should receive a hearing or not. That’s a problem.

“What they try to do is they use fear — ‘Oh, if you do anything, it will raise the cost (of construction).’ Bullshit.”

The TCEQ is unable to enforce even the existing rules, he said: “There’s no teeth at all.”

In an interview, Leftwich said additional regulation “is just unnecessary.” He said many of the complaints about APOs center on “nuisance issues like lighting, noise, all those type of things that comes along with any industry. It doesn’t matter if you’re a concrete batch plant or a trucking company or an H-E-B.”

Asked about cases of repeat violators in the Hill Country, Leftwich released a statement saying APOs “work very closely and in partnership with local, state and federal regulatory officials to address” environmental concerns immediately.

“The industry is extremely proud of its environmental operating record and highly values its commitment to the local communities in which it operates,” the statement said.

‘Quarry row’

One side effect of quarry operations is often impossible to see: the dust borne aloft by the blasting, excavation, transportation and processing of rocks.

TCEQ air permits allow the sites to emit microscopic particles that can penetrate the respiratory system and, in sufficient quantities and with sustained exposure, cause diseases such as lung cancer and stroke.

Some rocks, including limestone, contain high concentrations of crystalline silica, which can cause severe respiratory conditions such as silicosis. The particles are 100 times smaller than the sand found on beaches.

A TCEQ report released last year said overall emissions of particulate matter from quarries, including crystalline silica, are “minimal or negligible” — a conclusion based on monitoring conducted “near APOs.”

The testing was conducted with five monitors — four in the San Antonio area — placed in residential areas ranging from 0.3 miles to 1 mile from quarries. Many quarries operate machinery much closer to residential areas than 1 mile; the minimum buffer is 440 yards.

Wilson’s bill would have required all APOs to place air monitors at their property lines.

In 2002, residents living near “quarry row” — a stretch of 11 APOs in Comal County — requested a public hearing on an application by Cemex Construction Materials for a second rock crusher at its Balcones Quarry limestone plant. One resident, Barry Shea, said dust from the 1,500-acre site already was coating porches, patios, pet dishes and items stored in attics.

“I am concerned about the potential for respiratory problems, particularly for small children,” Shea told the TCEQ.

In its application, Cemex agreed to employ the “best available control technology” to control dust, including spraying the site with water and enclosing rocks as they move through machinery. The TCEQ, citing computer modeling, predicted that concentrations of particulate matter would stay within federal standards.

“It is not expected that existing health conditions will worsen or result in adverse effects to the health of the general public, sensitive subgroups, or animal life as a result of exposure to the expected levels” of particulate matter, the TCEQ wrote.

In 2003, the state denied the request for a hearing. Cemex installed its second rock crusher, which soon began grinding stone.

Three years later, the TCEQ fined the Balcones Quarry $12,600 after stormwater from the site flooded a resident’s property, damaging a fence and leaving behind “a lot” of sediment. A manager at the site was unable to show the TCEQ a stormwater pollution prevention plan, according to TCEQ records.

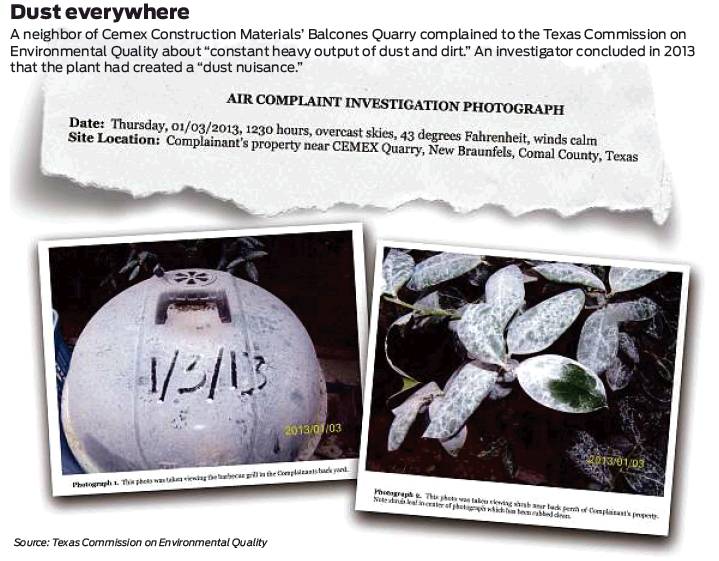

In 2012, a nearby resident, Maggie Parma, complained to the TCEQ that the quarry, which also operates a massive cement plant, was “creating a constant heavy output of dust and dirt.”

“The air is constantly polluted and everything is coated in dust,” she wrote.

In an interview, Parma, 58, said dust fell on her wooded homestead like snow. Many mornings, she would wipe dust from the windows of her car.

Parma grew up on the property in the 800 block of Krueger Canyon and was living there in 2012 with her elderly father; her grandchildren visited often.

“If you walked outside at night and you turned on a flashlight, you could see the dust in the air,” she said. “You know how snow flurries come down? It was like that, but in smaller bits.”

A TCEQ investigator who visited Parma’s property saw “a heavy coating of dust” on a BBQ grill and “all vegetation,” and a coating of dust on the windows of the home.

Driving toward the plant, the investigator saw “visible emissions” floating toward a neighborhood. She concluded that Cemex had created a “dust nuisance,” defined by the state as air pollution that “may tend to be injurious to or to adversely affect human health or welfare, animal life, vegetation, or property.”

The investigator recommended that the plant “prevent creation of nuisance conditions by minimizing dust emissions from leaving the property.”

A senior manager of external communications at Cemex did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

The problem persisted, and in 2015, Parma sold her 9-acre homestead to the quarry itself. The property had been in her family for 50 years.

Parma, who now lives in New Braunfels, scoffed at the state’s claim that current regulations are sufficient to protect human health and the environment.

“Yeah, whatever,” she said. “Then go live out there. It’s really unlivable.”

‘A very helpless feeling’

Kathleen Wilson, a woodworking artist, bought her slice of the Hill Country in Blanco County nearly three decades ago.

She planted flowers, shrubs and native trees — arroyo sweetwood, Mexican plum, Texas pistache — across a slope that rises gently above Flat Creek. She built a quirky, two-story structure out of recycled and native material — there are wood floors on the walls and white doors on the ceiling — and opened it as a bed and breakfast.

She calls it the Dream Shack Escape. Three rain catchment systems provide all the water she and her guests ever use. But in 2016, the arrival of the West Henly Site 4 miles upstream spoiled Wilson’s idyllic retreat.

For starters, there’s the dust.

“It gets on everything,” she said. “Every week, before people come, I wait until the morning of (to clean). If I do it two days before, I have to do it again.”

Then there’s the noise.

“It’s just constant, ‘boom, boom, boom, boom,’ breaking rock,” Wilson said.

Even more concerning to Wilson is the degradation of the creek, which runs through her property.

In 2016, the TCEQ received a complaint that the139-acre quarry, operated by a limited liability corporation called La Bala de Plata Investments, was not protecting a drainage ditch from construction activity. (The LLC, whose name is Spanish for “silver bullet,” did not respond to messages seeking comment.)

Even as it mined limestone, La Bala de Plata was developing about 10 acres of the site for commercial use. The company had not installed erosion or sediment controls at the construction site, causing sediment and rocks to spill into the drainage ditch and into culverts, a TCEQ investigation found. The investigator also found that a fence to trap silt had been improperly installed.

A manager at the West Henly Site later sent the agency photographs showing that the problems had been fixed.

Across the water from Wilson’s property, Mike and Connie Yerington, 73 and 72, respectively, run another getaway, Hillside Acres Retreat, on 26 acres they purchased a dozen years ago.

The vacation property features luxury cabins, a fishing pond, a swimming pool, an organic garden, free range chickens, beehives — and access to Flat Creek.

In 2017, Mike Yerington complained to the TCEQ that the creek had turned gray.

“I said basically, the water has never been cloudy before; now it’s cloudy,” he recalled. “We had not noticed any sediment in the creek until after the rock plant came in.”

A TCEQ investigator again found inadequate controls to stop sediment from spilling into the creek. There were “multiple breaches” in silt fencing, and a retention pond “did not appear sufficient” to handle runoff, the investigator wrote.

“Based on the observations ... the water quality complaint appeared to be substantiated,” the investigator wrote.

The quarry was cited for not preventing pollution; again, a site manager produced photographs showing that the silt fence had been repaired and the stormwater controls rebuilt.

Less than a year later, a third TCEQ investigation found that sediment again had spilled from the site into a tributary of Flat Creek. Again, a silt fence was not properly installed.

The document noted that a previous investigation had “cited the same or similar allegation.”

“Repeat violations may warrant formal enforcement by the TCEQ,” it said beneath photos of a chalky substance caking the ground.

Since then, the TCEQ has issued no enforcement orders against the site, according to the quarry’s compliance history report.

The same report lists the quarry as having a perfect compliance history from September 2015 through August 2020; its repeated violations have vanished from that public record.

A TCEQ official typed “NO” under the heading “Repeat Violator.”

The site’s operators told the TCEQ they’d built a berm and reinforced the fence to fix the problem. But the quarry’s neighbors say the pollution hasn’t stopped.

“It’s gotten worse with time,” Mike Yerington said.

The retired executive called the TCEQ “worthless and toothless.”

“Their enforcement arm, they go out and say, ‘Yeah, we have a problem here,’ but they don’t do anything about it,” he said. “It’s a very helpless feeling that when you do complain, they’re unable to do anything about it.”

‘A lack of understanding’

The recharge zone of the Edwards Aquifer stretches for more than 1,000 square miles across the Hill Country. Its exposed limestone serves as a conduit for rain to flow into the aquifer through cracks, crevices, caves and sinkholes.

Just south of Austin, the Hays Quarry Rock Crushing Plant blasts and excavates limestone in the recharge zone and the Onion Creek watershed. It sits on land that contains 70 sensitive, underground features that funnel water into the aquifer, a source of water for more than 2 million people in the region.

The quarry opened in 2005. Its operator, Industrial Asphalt, agreed to protect the aquifer and creek as part of a water pollution abatement plan approved by the TCEQ.

But in 2012, the company voluntarily disclosed that it had “disturbed ... several areas” it had promised to protect, “sealed” a cavity and built a road through a tributary in a protected buffer zone.

The quarry’s disclosures triggered a TCEQ investigation in 2014.

When investigators arrived on the 233-acre property, a quarry representative “discouraged” them from touring a protected buffer zone, TCEQ records said.

The investigators eventually found violations beyond what Industrial Asphalt had disclosed. They said the quarry had installed more than 2 acres of impervious cover, including roads and parking areas, without approval; had conducted construction activities in a protected buffer zone; and had sealed three more sensitive aquifer features — two cavities and a sinkhole — to build a new road, according to TCEQ records.

The investigators noted piles of waste on the sides of the creek where construction activity wasn’t allowed. They said sediment had been washed into a tributary that runs through the property.

Two years later, in 2016, a break in a berm at the quarry allowed “a large volume” of sediment-laden water to flow from a retention pond into a tributary of the creek, according to a TCEQ investigation report. Industrial Asphalt repaired the berm that year, the document said.

A year later, a gap between the berm and a silt fence allowed more sediment-laden water to flow into the creek.

In 2016, the state issued an enforcement order for the aquifer and buffer zone violations.

The penalty: $18,540.

The TCEQ agreed to shave more than $4,000 from the fine after Industrial Asphalt promised to update its procedures and train its workers, among other corrective steps.

In 2019, the quarry sealed another sensitive aquifer feature without prior approval, piling rock and concrete into a cavity.

“You do not have authorization to close a sensitive feature until you receive written authorization from TCEQ via an approval letter for the Encountered Feature Mitigation Plan,” a TCEQ environmental protection specialist emailed quarry representatives that day.

Joey Biasatti, vice president of sales for Summit Materials, the parent company of Industrial Asphalt, blamed the violation on “a lack of understanding,” despite the quarry’s assertion a few years earlier that it had trained its workers in how to deal with sensitive features.

“We discovered and sealed and then told TCEQ about it, and that was improper how we did that,” Biasatti said in an interview. “We have had some management changes within our business. Our intent is to abide by all regulations.”

Biasatti said Industrial Asphalt had fixed the issues raised in the 2016 enforcement order. He said the company, which is changing its name to Alleyton Resource, performed geological inspections, trained its workers to recognize aquifer features, paved a road to “eliminate washout” and fenced all buffer zones with barbed wire.

There are now only seven sensitive features in the mining area; the rest are in protected buffer zones, Biasatti said.

Unauthorized sealing of sensitive features can damage the aquifer in various ways, said Marc Friberg, executive director of external and regulatory affairs at the Edwards Aquifer Authority.

“One, it keeps it from recharging,” Friberg said, “and two, if they’re done improperly, they have the potential to increase opportunities for contaminating the aquifer.”

The House committee report on the aggregates industry concluded that the state’s water pollution abatement program “is not sufficient” to protect the aquifer’s recharge zone and should be stiffened to require more inspections.

Dupre, the professor of geology and sedimentology, said the problem is an urgent one.

“The issue with TCEQ not even reinforcing their own regulations, much less adopting harder regulations, has been a real nightmare,” Dupre said. “And it’s made enforcing issues exceptionally difficult. We’re just hoping there will be a change in attitude. But it’s a hard one. I mean, we’re in Texas.”

COMING TUESDAY:

Life on Quarry Row bchasnoff@express-news.net

At ExpressNews.com/ Blast-Zone

» Search for your address to find nearby quarries.

» Explore how the Colorado River changed course after a quarry opened.

» See drone footage of Hill Country quarries and rock blasting.