A vanishing way of life?

Growth in N.W. Bexar leads to concerns about environment and water

By Elena Bruess STAFF WRITER

Laurel Porter knows her corner of Northwest Bexar County so well she could draw a map of it with her eyes closed. Just south of Boerne, sloping valleys and chalky canyons line twisting roads that pass by the cities of Grey Forest, Helotes and Fair Oaks Ranch.

Since she was a girl, Porter has visited a 5-acre spot just off Interstate 10 at the Bexar-Kendall county line to work with horses at the equestrian Campbell Urban Training Center. The owners, Rick and Judy Urban, became her second family. She loved it so much she returned to buy a 5-acre property next to the Ur-bans’ land.

Porter, 38, has a horse, a donkey, two dogs and a pig named Mr. Pigglesworth at her place just behind the equestrian center, where the Urbans care for 17 horses. The area has been Porter’s home for decades, a piece of the Hill Country she couldn’t imagine living without.

So when she heard that a developer had proposed building a 600-unit apartment complex next to her home, she felt like her world was crashing down on her.

She’s concerned about dust and noise from construction and the effects on water quality and the environment once the apartments are built and the renters arrive.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen with all the animals,” she said. “I’m worried people won’t want to board their horses here anymore. Then what do we do?”

Many people are concerned about such development in the area, which has spurred angst and consternation among residents over the environment, growth, water and their way of life. They wonder what the area will look like two decades from now.

Developers’ interest in the northwest portion of Bexar County isn’t surprising. The area offers good schools and a high standard of living, and it’s close to popular destinations such as The Rim and La Cantera.

Porter’s segment of the Hill Country is known as the Scenic Loop-Boerne Stage Corridor.

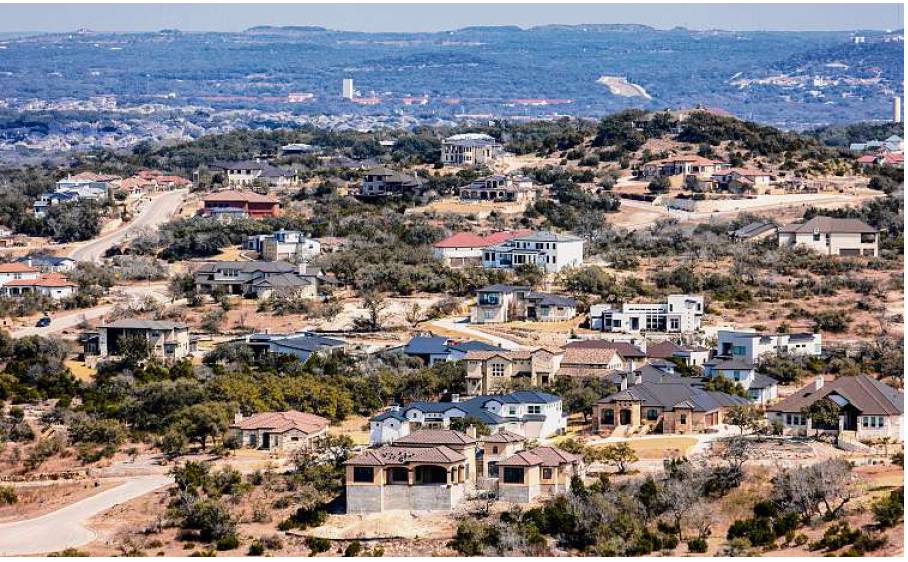

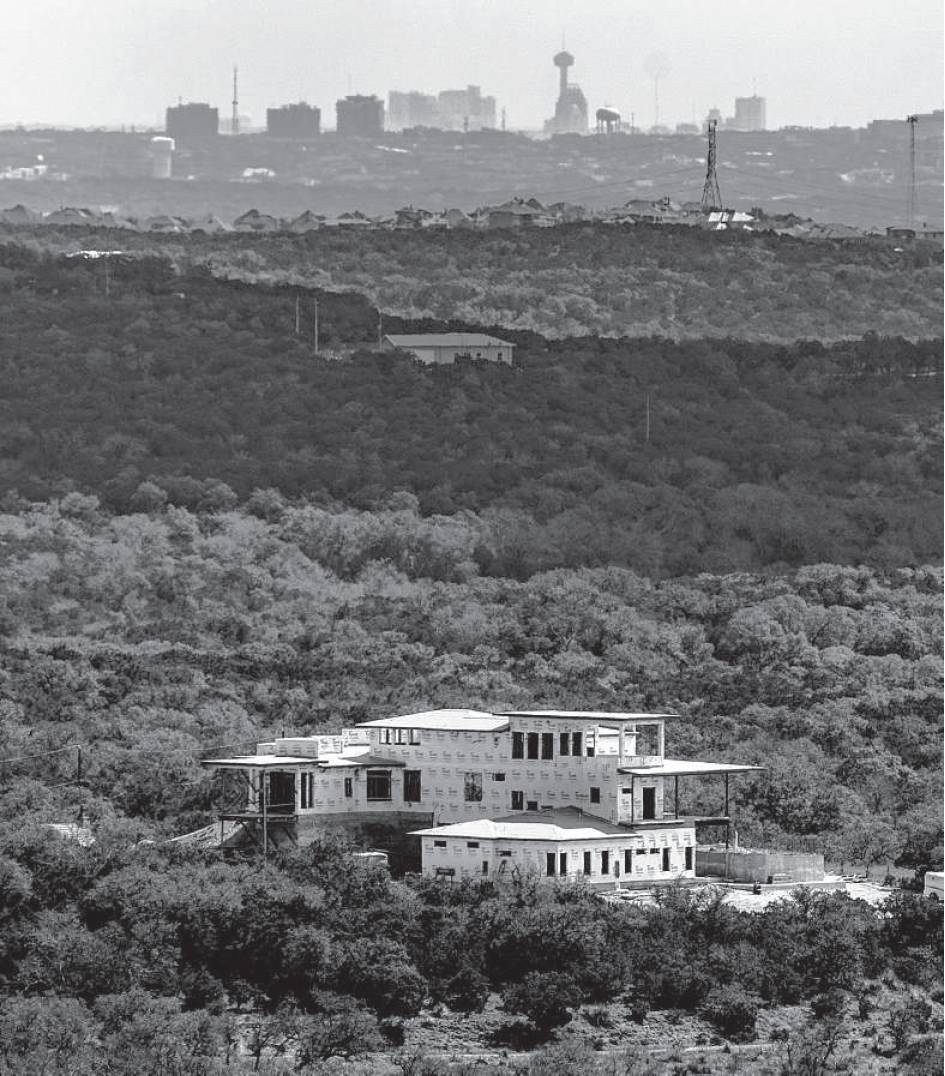

Scenic Loop and Boerne Stage roads meander north of San Antonio, cutting through hills, creeks and limestone cliffs and over the vulnerable Edwards Aquifer — which serves 2.5 million people and is home to eight endangered species. For centuries, the area was ranch land, undeveloped and wild. But in the past two decades, it has experienced exponential growth.

From 2000 to 2020, the corridor grew by nearly 107,034 people, an increase of almost 133 percent, records show. From 2002 to 2022, land there has been subdivided into more than 25,000 new parcels, an 87 percent increase, according to a San Antonio Express-News analysis of parcel data.

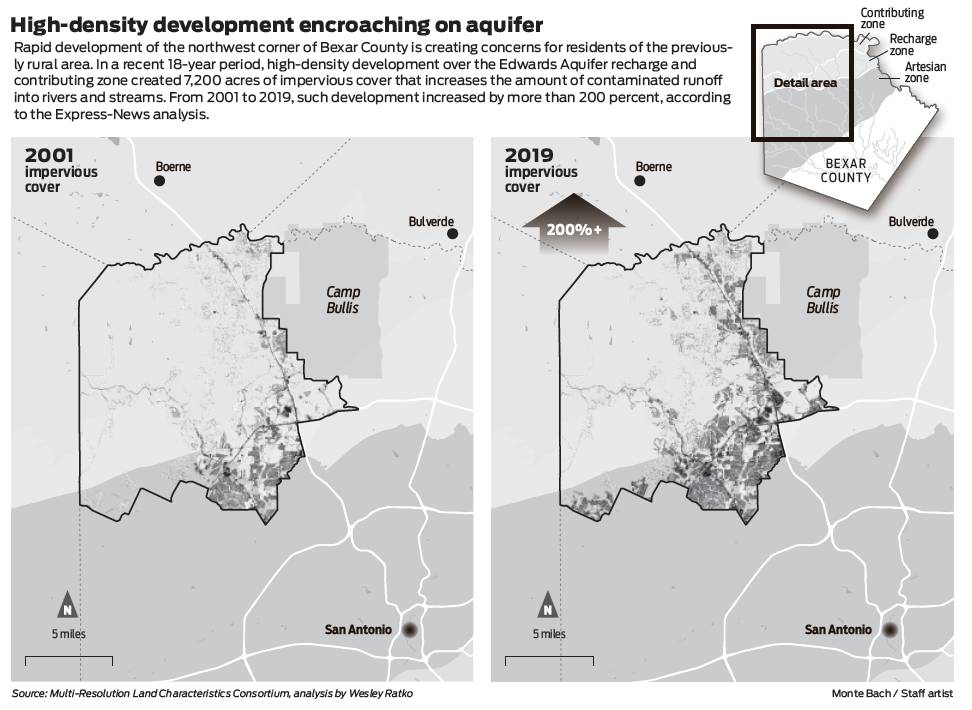

And much of the growth has been in high-density development, where 80 percent to 100 percent of the land is covered with impervious materials — such as sidewalks, driveways and streets — that increase the amount of contaminated runoff into rivers and streams.

From 2001 to 2019, such development increased by more than 200 percent.

All of this has led to more traffic and new road construction as developers plan subdivisions, apartment complexes and mixed-use projects.

“I can’t imagine staying here after this,” Porter said. “It feels like I’m being kicked out of my home.”

The city of San Antonio and other local governments have little authority to manage growth in the area.

“One of the chief challenges is that San Antonio specifically has very little tools to manage the growth in those sensitive areas and in the county,” Mayor Ron Nirenberg said. “Virtually no tools exist.”

Limited regulations

When Porter saw that the proposed apartment project could threaten her and her neighbors’ way of life, she immersed herself in Bexar County’s development regulations to see whether there was anything she could do. She found a complicated maze of rules and restrictions — and few answers.

However, Porter did learn a few key facts: She and the Ur-bans live on unincorporated land within 5 miles of San Antonio city limits, known as the extraterritorial jurisdiction, or ETJ. The ETJ does not have city zoning, and, as a result, if developers want to build an apartment complex next to a farm, they can — with few if any local regulatory hurdles.

The only restriction on the land next to Porter’s was a density limit stemming from its proximity to Camp Bullis. The aim of the restriction is to protect the military training post from residential and commercial encroachment and light pollution.

“San Antonio specifically has very little tools to manage the growth in those sensitive areas and in the county.”

Mayor Ron Nirenberg

But it wasn’t an obstacle for long. When developers sought to build the apartment complex, they got the limit changed from a low- to a medium-density development — needed to accommodate the project — with the Army’s approval.

Porter and the Urbans didn’t find out about the complex — called the Lux at Lemon Creek — until April 27, when the city’s Planning Commission approved the density for developer Garrett Glass at Source-Texas LLC. On May 19, the City Council also approved the change with little discussion, despite neighboring landowners’ pleas.

“It’s been a way of life for us for a long time,” Judy Urban told the City Council in May. “The watershed, the environment, the horses, especially the ones we’ve been training.”

The Urbans have called their farm on Fredericksburg Road home since 1996. Now in their early 70s, Rick and Judy expected to live the rest of their lives there — or have at least another decade before the area changed too much.

Judy Urban said it’s impossible to build a home and business comparable to what they enjoy now for the money they could get selling their property.

They wonder whether the developer can at least erect a wall between their properties, though it wouldn’t shield them from the dust, noise and increased traffic.

Neither Glass nor his attorney, Kevin DeAnda of the law firm Brown & Ortiz, responded to requests for comment.

The city’s Unified Development Code includes regulations to protect people and the environment, with requirements to control drainage and stormwater and to protect the watershed. Meanwhile, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality enforces regulations related to the Edwards Aquifer’s recharge and contributing zones.

In the recharge zone, water filters into the aquifer through porous limestone. In the contributing zone, rugged, scrub-and tree-covered landscapes “catch” rainwater, which flows into streams that carry it to the recharge zone.

Many advocates for a healthy environment believe neither the city nor state regulations go far enough, and some are trying to get San Antonio officials to amend the UDC this year to incorporate stricter rules.

Porter’s and the Urbans’ properties are over the aquifer’s contributing zone and near normally dry Cibolo Creek.

In an effort to manage San Antonio’s growth, the city in 2016 adopted the SA Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan, a 25-year framework. Among other things, the plan calls for more development on vacant urban parcels.

In 2010, the city adopted the North Sector Plan to guide development in areas north of Loop 410. The plan suggested so-called zoning tiers for different areas of the North Side, such as country tiers designated for large lots and suburban tiers that allow low- to medium-density development.

But in practice, developers routinely have obtained amendments to accommodate subdivisions that clashed with the tiers in which they were planned.

From 2013 to 2021, the Planning Commission recommended 85 proposed plan amendments out of 180 filed cases, which the City Council later approved, according to a study by the Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance, an environmental nonprofit.

Twenty-six of the changes were over the aquifer recharge zone, and 28 were over the contributing zone. Two were between the two zones.

“All the developers would have to do is meet our very limited regulations and move forward with the plan,” said Rudy Nino, assistant director of the city’s Planning Department. “Only if the developers need some special consent from the city, then we could negotiate the types of developments that would be closer to our adopted plan.”

In one such case, the developer of the Guajolote Ranch tract — a contentious proposed residential project spanning 1,160 acres between Helotes and Chiminea creeks in the ETJ, a few miles from the recharge zone — will have to apply for a special city permit to build its own wastewater treatment plant.

That led to negotiations between the San Antonio Water System and developer Lennar Homes of Texas that yielded several protective concessions, said Tracey Lehmann, SAWS’ director of development. They included limiting impervious cover to 30 percent, setting aside 50 percent of the project as open space and hiring an A-level wastewater operator — the highest level of certification — to manage the treatment plant.

Nevertheless, most developments can be built without such requirements. They’re generally dealt with on a case-by-case basis, Lehmann said. And even with concessions on developments such as Guajolote Ranch, critics are concerned the regulations are inadequate.

The Guajolote Ranch tract was originally designated in the North Sector Plan as part of the rural estate tier. But the developers were able to have the plan amended. While there have been numerous developments in the area, this project will be the densest so far, with 3,000 houses, or two per acre.

“We all know the rules of the game here,” Nino said. “We all know what the processes are and what the state allows us to do and not to do. We’re just trying to work with that.”

Approaching tipping point

Besides their equestrian-centric lifestyle, the Urbans are concerned about the proposed apartment complex’s long-term effects on the environment, particularly water runoff.

Residents near the planned Guajolote Ranch development have similar concerns.

In 2018, as part of the city’s Edwards Aquifer Protection Plan, San Antonio-based Southwest Research Institute studied the effects of wastewater facilities on the Helotes Creek watershed, which runs through a section of Scenic Loop and Boerne Stage roads. Researchers found that further development and additional wastewater systems would degrade the watershed and the quality of water recharging the Edwards Aquifer. The results, they said, held true for most watersheds over the recharge and contributing zones.

Nutrients in wastewater, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, can cause algae growth and compromise the watershed, said Ron Greene, an SwRI scientist who worked on the study.

Contaminants can travel from the contributing zone — in waterways such as Cibolo and Helotes creeks — to individual wells with no chance for the water to be filtered or to eliminate harmful pathogens, such as E. Coli or coliform.

Green said the Guajolate Ranch project might not irrevocably contaminate the Edwards Aquifer, but it could set a precedent for more high-density developments over the recharge and contributing zones and eventually shift the overall ecological balance.

The Edwards Aquifer Authority is likewise seeking balance. EAA general manager Roland Ruiz said developers and homeowners must have a greater sense of responsibility for protecting natural resources.

The EAA over the years has sought ways to make development more sustainable. It has improved its technology and research capabilities to include a sharper analysis of contaminants in the aquifer’s watershed and more trend mapping, such as monitoring one well’s health over years. It’s also been researching best practices for sustainable development, such as how to deal with waste being discharged, capturing rain or incorporating systems to manage stormwater runoff.

“This all takes time,” Ruiz said. “But we’re moving in the right direction.”

Infrastructure challenges

While developers attracted to Northwest Bexar County have often been able to get density limits relaxed, they face challenges in building there. Many tracts aren’t big enough to accommodate large-scale development, such as a 250-plus-acre development, according to the Real Estate Council of San Antonio, and utilities aren’t readily available in some areas.

SAWS’ certificates of convenience and necessity — which designate the boundaries within which the city-owned utility must provide water and wastewater service — don’t completely cover Northwest Bexar County. Developers seeking to build in those gaps must get SAWS to extend pipelines or find other ways to deliver those services.

SAWS receives a steady stream of proposals from developers, who must determine whether they can receive water services before they apply for city permits or start construction. And if SAWS builds new infrastructure to grant such service requests, it can attract other developers, said Amy Hardberger, a SAWS board trustee.

“If you build it, they will come,” she said.

For the planned apartments next to Porter’s farm, which is just outside SAWS’ territory, the developers will tap into the water supply that was built for Lemon Creek Ranch nearby. Because the development is in San Antonio’s ETJ, SAWS is more inclined to provide service.

At the SAWS board’s next meeting this month, it is likely to approve water and wastewater service for the complex.

Providing the infrastructure gives SAWS a tool to protect the environment and avoid the installation of multiple septic systems. On the other hand, developments that rely on septic systems are generally lower density, which environmental advocates prefer.

Robert Puente, the utility’s CEO, said SAWS will follow the city’s lead. If the city adopts stricter regulations over the Edwards Aquifer or promotes housing elsewhere, SAWS can act accordingly. Puente cited a massive wastewater pipeline that the utility built a decade ago on the West Side that prompted developers to begin building in that area rather than on the Northwest Side — steering clear of the aquifer.

“Developers would have more of an incentive to build where there’s already wastewater, rather than applying and going through the whole process,” Puente said. “We could do something like that on the South Side or East, but we need that lead from the city to redirect growth.”

Nirenberg is aware of such discussions — he sits on SAWS’ board.

He said improving the SA Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan is key to balancing development and environmental concerns.

“It’s clear through these different issues that come up quite often that we need a growth management strategy that goes a bit further into policy, and how we manage that growth — our community’s goals — are through SA Tomorrow,” Nirenberg said. “I’m hopeful it will continue to be improved because it needs to.”

Any changes in regulating development and managing growth, however, will be too late for Porter and the Urbans. Under the current rules, they had little, if any, ability to stop the proposed apartment complex from being built next to them.

The developers suggested buying their land and finding comparable land for them, an offer that Porter viewed skeptically, saying that none of the proposed compromises felt right for her.

Eleven of Porter’s neighbors were notified about the new development, but only she and the Urbans showed up to fight it. It seemed to them like they were predestined to lose.

“The developer told me if they didn’t develop, someone else would,” she said. “So I guess that’s that.”

Elena Bruess writes for the Express-News through Report for

America, a national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms. ReportforAmerica.org . elena.bruess@express-news.net