Disappearing way of life

Surging development in the Hill Country has its small towns worried

By Annie Blanks STAFF WRITER

Gone are the days when the Texas Hill Country was just that — rolling hills as the backdrop to a country way of life, a relatively undeveloped and untouched region of the Lone Star State.

Gone are the days when dark skies were actually dark, longhorns roamed in wide-open fields for miles and miles, and major rivers from the Sabinal to the San Marcos snaked unobstructed through the plains.

The Texas Hill Country has officially been discovered, and there’s no turning back.

“There’s a gold rush mindset in terms of development in the Hill Country,” said Connie Barron, a city councilwoman in Blanco and a board member of the Hill Country Alliance. “And, unfortunately, there’s little to no regard for what that will mean for the future of the region.”

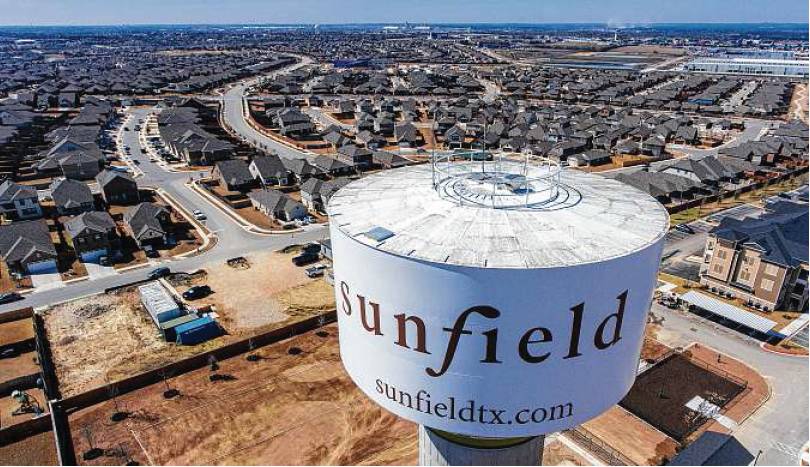

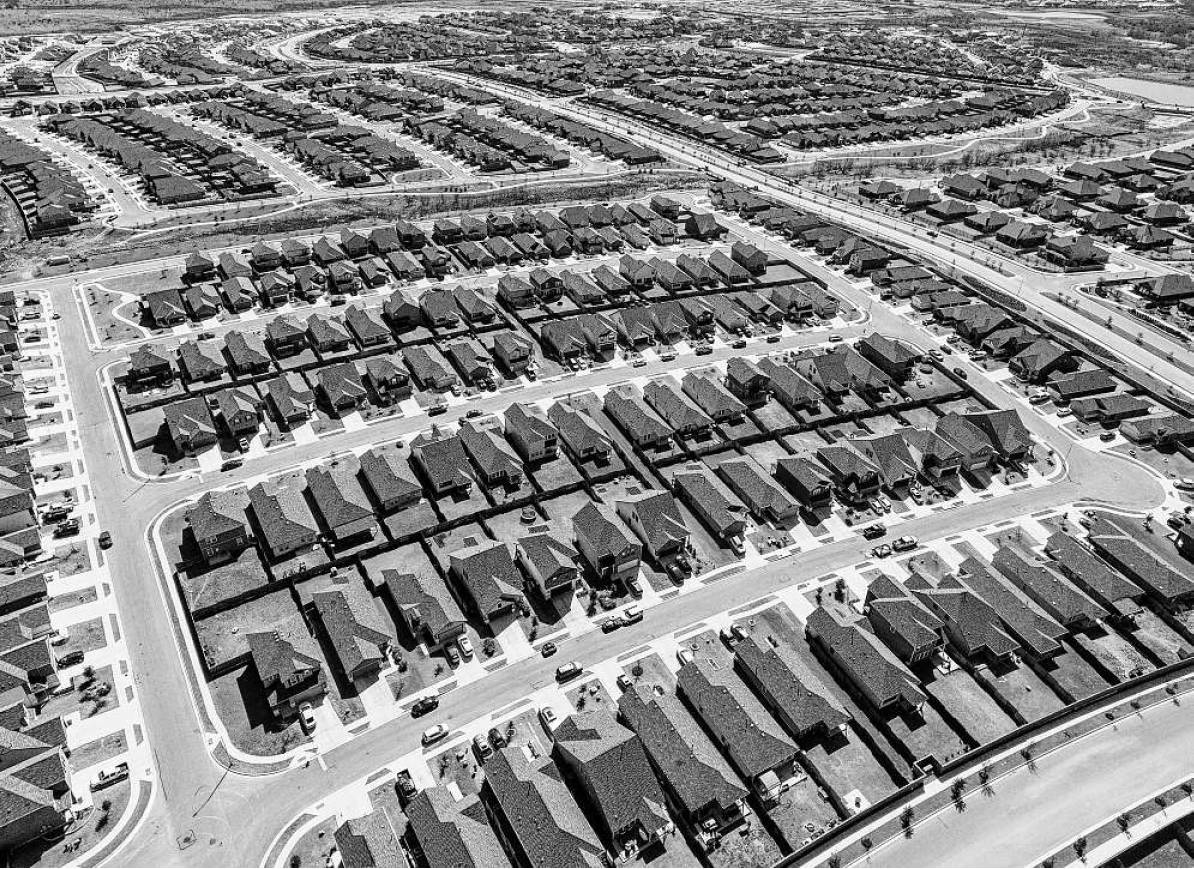

The Hill Country is one of the fastest-growing regions in the nation, according to the 2020 census, and leaders of the small towns that dot the region say that makes them increasingly concerned. Developers are flooding the Hill Country with thousand-plus-homes subdivisions, often overwhelming small-town infrastructure and placing the “Hill Country way of life” in jeopardy.

The Hill Country Alliance, a nonprofit that counts more than 11 million acres in 18 counties as its namesake region, works to preserve the environment and strengthen conservation efforts amid explosive growth. In addition to the big cities of San Antonio and Austin, the region is home to the headwaters of 12 Texas rivers.

But as growth soars in the major metro areas, spillover has led to a development boom in the Hill Country. Homebuilders from across Texas are gobbling up available land, which is often in unincorporated parts of rural counties that have little government oversight.

Katherine Romans, executive director of the Hill Country Alliance, said the pandemic has only accelerated the rate of “fragmentation” in the region — the splitting up of large tracts of land to make way for dense development.

“We always knew that to be a challenge — the loss of family ranching land, the subdivision of large tracts of wildlife habitat and open spaces,” she said. “But it has intensified over the last two years.”

Blanco, for instance, is attempting to fend off a 1,500-home subdivision that would more than double the city’s population of 1,800 when finished. And Buda is preparing for a 2,500-home subdivision in its extraterritorial jurisdiction that’s being built despite near universal opposition from city leaders who say they just can’t handle the additional stress on their infrastructure.

Ranchers in Dripping Springs are preparing for the possibility that Hays County will exercise eminent domain over their lands to build a four-lane highway through the hills to accommodate increased traffic associated with the population boom.

The developers are often at odds with city leaders who want to preserve the once-quiet Hill Country way of life, said Colin Strother, a political strategist who lives in Buda and served on the town’s planning and zoning commission for 10 years.

“These developers, they don’t give a damn about us,” he said. “They just don’t care.”

Cities can’t manage growth

The Hill Country Alliance, or HCA, has carefully tracked population growth in the region over the past 20 years.

Nearly 3.8 million people lived in the Hill Country as of 2020, according to the HCA, a growth of almost 50 percent since 2000. The region is expected to grow by 35 percent over the next 20 years, reaching 5.2 million people by 2040.

And while some of that growth has taken place within city limits, in cities such as Fredericksburg, Boerne and Kerrville, most of it has happened in unincorporated areas — places that are not located within city limits and aren’t subject to city rules and regulations.

More than 864,000 people lived in unincorporated areas of the Hill Country in 2020, according to the HCA — a jump of 103 percent since 1990.

The mass migration into unincorporated areas of the Hill Country is reflected best in places like Bandera and Medina counties. According to the 2021 State of the Hill Country Report — for which the HCA analyzed the region’s population growth, water quality and conservation efforts — the population in unincorporated areas of Bandera County more than doubled after 1990.

Meanwhile, the city of Band-era’s population stayed nearly the same. And in Medina County, the populations of several cities decreased after the 1990s, while the county’s overall population expanded.

The growth of unincorporated areas is important because counties have fewer tools to manage and plan for responsible growth than cities do, per Texas law. Developers are able to build subdivisions in unincorporated areas of counties without having to be subject to cities’ density, zoning or wastewater regulations.

“Texas is the only state in the country that does not allow counties tools to plan for and manage growth,” the HCA’s Romans said. “We are seeing this huge amount of growth come to our region, and more and more incompatible land uses coming in next to each other.”

That can look like a concrete plant coming in across from a hospital, or an amphitheater with large outdoor lights coming in next to a quiet neighborhood.

Representatives from the Greater San Antonio Builders Association, the Home Builders Association of Greater Austin and the Hill Country Builders Association did not return multiple requests for comment for this story.

Many city leaders point to the passage of House Bill 347 in 2019 as the impetus for a lot of developer takeover in the Hill Country. The bill ended involuntary municipal annexation, or the ability of a city to annex parts of unincorporated county territory into its city limits without voter approval.

The bill was heralded by many as a way for those who live in unincorporated areas to not have to be involuntarily annexed into a city, thereby becoming subject to increased city regulations and taxation.

But the bill has had the unintended consequence, some say, of preventing cities from being able to get a better handle on development on the outskirts of their limits, most often in their extraterritorial jurisdictions, or ETJs. Developers will take advantage of the little county oversight and build large subdivisions in a city’s ETJ, while being close enough to a city to still require its water, wastewater, emergency and public service resources.

Barron, the Blanco councilwoman, said the bill effectively stripped cities of their ability to have “more control and protection, and greater opportunity for revenue” necessary to sustain a small town in the Hill Country.

“At the same time, it is empowering developers to come into these unincorporated areas and build their own infrastructure to create incredibly dense communities right on our outskirts,” she said.

Strother, the political strategist in Buda, said HB347 was akin to the Legislature taking a “meat cleaver” to cities’ abilities to control growth and development.

“They just lopped off a whole section of the code that gave cities what little power we did have to help manage our own growth,” Strother said.

Effect on water supply

One of the main concerns of increased development is the effect on the environment, particularly with the strain that all the new houses are placing on the Trinity and Edwards aquifers — the two main aquifers that supply drinking water to the Hill Country.

Barron likened the current water supply situation to a glass of water that used to have just one or two straws in it. Now it has 10 or 11.

“We just can’t keep putting more and more straws into the same glass of water and expect it to last as long as it lasted when there was just one in that glass,” she said.

Simply put, more houses and subdivisions means more groundwater pumping from the aquifers, which could, in theory, lead some of the wells that pump from them to dry up.

Jacob’s Well, one of the most well-known and important spring wells in the region, went dry for the first time in the late 2000s because of a combination of excessive pumping and drought, after never having run dry in recorded geographical history. It’s run dry a number of times since then, Romans said.

“We know the Hill Country was once the land of 1,100 springs, but unfortunately we don’t know how many of the original springs are still running,” she said. “The point is, once we start losing those springs, we see dramatic and irreversible impacts on the surface water.”

The Edwards Aquifer Authority and local groundwater conservation districts manage and cap water permits. They have been working for years to manage the number of new water permits that are issued so new homes or businesses can be built.

But developers and environmental purposes still can be “at odds with each other” sometimes, said Roland Ruiz, general manager of the Edwards Aquifer Authority. He said it’s up to developers and environmental stakeholders to take into account things such as groundwater supply, endangered species and conservation efforts when planning for new growth in the Hill Country.

“It’s complicated and complex,” Ruiz said. “But we believe there’s a workable path forward, and that’s why we do what we do — so that we can, perhaps, move forward together.”

Strother said the draw of the Hill Country is still its “rolling hills, starry skies” and proximity to the big cities.

But the big-city folks who want to live in the Hill Country are ultimately going to be its demise, he said.

“These actions aren’t just hurting the small communities. It’s hurting the entire region because we don’t have adequate infrastructure to handle this at all,” he said. “As a result of this unchecked growth, we’re damaging the entire region.”

Annie Blanks writes for the

Express-News through Report for America, a national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms.