HC INVESTIGATION: UNFAIR BURDEN

A TAX SANCTUARY

Religious organizations across Texas use obscure law to own tax-free homes for clergy

By Eric Dexheimer, Jay Root and Stephanie Lamm STAFF WRITERS

This fall, county officials mailed out property tax bills to the owners of a 10-bedroom, 10.5-bath Houston-area mansion, an 8,000-square-foot residence in a historic San Antonio neighborhood, an elegant Highland Park estate in Dallas and a house on more than an acre overlooking Corpus Christi Bay. The homes are worth millions of dollars. In each case, their 2021 tax bill was identical:

Zero.

Most people know that religious organizations pay no property taxes on their houses of worship. Lesser known is that many also get a valuable break on residences for their clergy as well.

The word “parsonage,” as these residences are called, conjures images of humble, spartan rooms attached to drafty churches. A few still are.

Yet in many places across Texas, parsonages are extravagant estates nestled in the state’s most exclusive enclaves. Like their wealthy neighbors, the clergy occupants enjoy spacious and well-appointed homes, immaculate grounds, tennis courts, swimming pools, decorative fountains and serene grottos.

Unlike their neighbors, the parsonage owners pay nothing in taxes, leaving other Texans to backfill the uncollected revenue to cover the cost of schools, police and firefighters.

State law allows religious organizations to claim tax-free clergy residences of up to 1 acre. Yet each of the state’s counties has its own appraiser responsible for overseeing local properties. So no one entity has examined how many parsonages there are in Texas, their value and their legality.

A first-of-its-kind Houston Chronicle investigation analyzing thousands of pages of property records found:

•The state’s most populous counties identified 2,683 parsonages worth about $1 billion, costing other residents who must fund school districts and local governments $16 million every year. The true cost is almost certainly higher because several large counties did not or could not respond, and even those that did conceded they did not regularly update values for the tax-exempt properties.

• There is no dollar limit to a parsonage’s tax exemption. At least 28 of the clergy residences were worth more than $1 million.

•Compared to some other states, Texas’ parsonage law is vague and permissive, allowing appraisers little leverage to question the legitimacy of a religion or clergy member. A lack of enforcement authority means the process effectively operates on the honor system.

•Across Texas’ largest counties, the Chronicle identified more than 30 parsonages for which appraisers had granted the 100 percent tax break even though they exceed the law’s 1-acre limit. Presented with the Chronicle’s findings, 13 appraisal districts said they were initiating reviews of parsonages in their jurisdictions.

“If you’re trying to paint a picture of there’s a lot of abuse in the clergy exemption, it does a pretty good job with that,” Brent South, chief appraiser in Hunt County and former president of the Texas Association of Appraisal Districts, said of the newspaper’s investigation. “The numbers don’t lie.”

Supporters say the clergy residence tax break can offset living costs for spiritual leaders earning low salaries. It also permits religious charities to perform more good work, lightening the government’s burden of caring for the less fortunate.

“Keeping families together, serving the disadvantaged, caring for seniors and children, providing a beacon of faith in these challenging times — our work is more important than ever,” said Sarah Good, executive director of Highland Park Presbyterian Church.

Yet Texas already grants 100-percent tax breaks on tens of billions of dollars worth of property owned by religious organizations. The off-site parsonages add hundreds of millions more to that figure.

“Church organizations get more benefits than any other exempt entities in the tax code,” said John Brusniak, a Dallas attorney considered one of the state’s foremost authorities on Texas property tax law who has represented churches.

“The churches get three square meals,” added Nueces County Chief Appraiser Ramiro “Ronnie” Canales. “Plus dessert.”

Property taxes pay for much of the state’s public education as well as for government operations, from city hall to hospital districts. Every tax dollar not contributed by a church for a clergy leader’s home is money other local property owners must make up to cover the government’s costs.

“As you exempt more people — give more and more exemptions — it shifts the tax burden to the other property owners,” said Tony Belinoski, chief appraiser for the Montgomery Central Appraisal District.

Fewer collected local school property taxes also trickle up to state government, which must find the money elsewhere to fill out its school finance commitments, added Dick Lavine, a fiscal analyst for Every Texan, a left-leaning think tank.

“The state’s going to have to make up the difference with sales tax or wherever it’s going to get its money, which may mean less money for other parts of the state budget,” he said.

Many of the tax-free clergy residences are modest homes. More than half of the 200 or so parsonages in Bexar County, for example, are valued below the county’s average home price of about $251,000.

But a significant number of parsonages have values that soar well above their surrounding communities. In Travis County, the 3,700-square-foot Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary parsonage set on slightly less than an acre is appraised at $3.33 million.

If it weren’t considered a parsonage, the property’s owner would contribute $72,500 a year in taxes.

Well-off religious organizations that clearly have the means to afford their taxes don’t have to seek the exemption. Lakewood Church did not ask the Harris County appraiser for a tax break on the 15,000-square-foot residence of the state’s most famous prosperity gospel preacher, Joel Osteen. His annual tax bill comes to $218,000 a year, according to county tax records.

Osteen, who hasn’t taken a salary since 2004, believes it’s important for donors to know all their money goes to the church, said his brother-in-law, Don Illof.

“He could take the parsonage break,” Illof said. “But he pays his property taxes, just like he’s supposed to.”

Property records also show that San Antonio’s Cornerstone Church didn’t seek an exemption for any clergy residences in Bexar County. Appraisal records show its well-known spiritual leader, John Hagee, pays $42,000 annually in property taxes. A spokesman said the matter was personal and declined to comment.

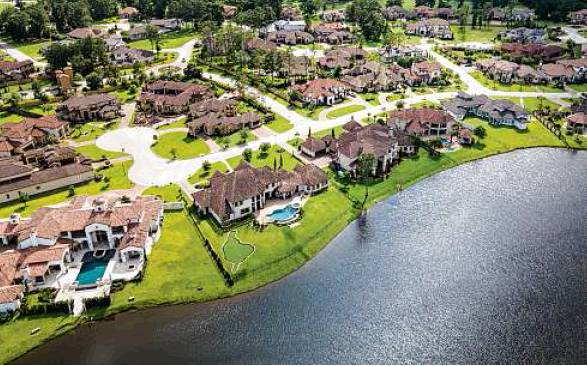

But Harris County Appraisal District documents show New Light Church World Outreach & Worship Centers pays no taxes on its nearly 25,000-square-foot mansion in Spring perched on the shore of a private lake and occupied by its high-profile leader, I.V. Hilliard. The 11.8-acre lot includes three hot tubs, two fountains and a swimming pool and tennis court, property records show.

Hilliard’s wife told appraisal officials it was their home, district documents show.

“Because Bishop Hilliard and his wife are living there, we are treating the 24,900-square-foot home as a parsonage,” said Jack Barnett, a spokesman for the Harris district.

New Light’s attorney, Malachi Johnson, said “Apostle Hilliard occupies only a portion” of the home and that the “primary use” of the property, which in addition to the mansion includes six other homes, was a “minister’s retreat and conference center” that qualified for its tax break as a place of religious worship.

Johnson added that the large “H” adorning the wrought-iron gate surrounding the property didn’t refer to Hilliard but to the biblical word Hamath — a city of “wealth and prosperity.” The tax break on the property where Hilliard lives saves New Light $100,000 a year in forgone property taxes.

Some religious organizations maintain deluxe accommodations for their clergy that appear at odds with their self-described austere values.

“Vowed to the Gospel counsels of poverty, chastity and obedience, we seek interior conversion so as to become men of simplicity, prayer and penance,” the Capuchin Province of Mid-America Mission Fund explains on its website. Yet in 2019, it purchased an 8,430-square-foot “mid-century gated masterpiece” in San Antonio assessed at $1.43 million for its seminarians. The listing ad featured a black Ferrari.

“We have to live somewhere,” said Brother Mark Schenk, provincial minister for the organization. He said the poverty vows were made by individuals, not the institution.

The annual cost to Bexar County taxpayers of removing the 1-acre property from the tax rolls: $36,500.

The power of the church

Religious organizations have always wielded Texas-size influence in state politics. Their clout is visible not only in the state’s restrictive gambling, alcohol and abortion laws but also in the broad range of tax benefits they continue to accrue. This year, at the urging of the Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops and the faith-based Texas Values, legislators increased from six to 10 years the length of time churches can skip property taxes on vacant land they intend to develop in the future.

At one time, Texas taxed clergy residences. While buildings used for worship are exempt, “it is clear that the Legislature did not have in view the exemption of a parsonage built on a lot contiguous to a church lot any more than built on a different block or miles away,” an appeals court concluded in a 1918 case in which the justices denied a Methodist church’s attempt to avoid taxes on its San Antonio clergy residence.

Soon after, though, Texas lawmakers decided to put the parsonage question to residents. In 1928, voters handily approved a clergy residence exemption as a new constitutional amendment. Legislators wrote it into law a year later. An attempt to limit the tax break by capping the value of the homes that could be exempted was quickly discarded, legislative records show.

Most states have a parsonage exemption, but some impose strict standards on applicants.

In California, organizations must demonstrate the parsonage is necessary to accomplish its religious goals. Pennsylvania law doesn’t specifically define a parsonage, so it is up to the churches to prove the exemption is essential to their missions — a high bar, said Paul Morcom, a Harrisburg attorney and author of “Assessment Law and Procedure in Pennsylvania.”

“If you have the right set of facts, you could get an exemption,” he said. “But most likely you won’t.”

New York applicants must describe the clergy leader’s training and accreditation. Montana limits the total acreage a single church can claim as tax-free. Maine limits the value of the parsonage that can be claimed as exempt.

The Texas parsonage law, by comparison, requires only the barest of standards. Applicants typically need answer only four yes-no questions to qualify.

“As long as I can check the boxes that are required to qualify for a religious exemption, an appraisal district is pretty much in a position of granting that exemption,” said Bexar County chief appraiser Michael Amezquita.

The residence must be owned by a religious organization and considered “reasonably necessary” to worship. Occupants are limited to those whose “principal occupation is to serve in the clergy” — though clergy is left undefined.

Appraisers say the skimpy statute gives them virtually no legal toeholds to critically evaluate an application or reject a parsonage request for any reason other than improperly submitting the basic paperwork required.

“The code is too vague, too generous,” said McLennan County Chief Appraiser Joe Don Bobbitt. “Too ripe for abuse.”

Defining a religion

In 1984, after devoting his youth to mastering martial arts, Ivan Ujueta “accepted Christ as Lord,” according to online biographies. Soon after, he founded a new martial arts discipline “with Christ being the foundation of this system.”

His Family Vision Center applied for and received a 100-percent religious property tax exemption from Bexar County for a new 5,900-square-foot residence in Helotes, a small city northwest of San Antonio. It claimed a portion of the structure as his living quarters — a parsonage — with the rest dedicated to his melded martial arts/religious practice stressing how to “disable a man from doing wrong and enable him to do right.”

While a martial arts-based church may not meet everyone’s definition of a religion due a tax break — currently worth more than $23,000 a year — when it comes to the property exemptions, Texas law gives appraisers little discretion.

“If you come and tell me that you have some religion, and basically all you do is color all day and that’s your religion, I can’t judge and say it’s not religion,” said Marquesa Esparza, who oversees exempt properties for Bexar Appraisal District.

Church lawyers say that’s how it should be.

“How does the state tell a church what is reasonably necessary or not for you to practice your religion?” said Darren Moore, a Fort Worth attorney who represents religious organizations in tax matters.

Yet appraisers say in practice it means they have little leverage to aggressively apply even the low legal hurdles described by the Texas law.

“There’s not a lot when you read the actual law itself,” said Tarrant County Chief Appraiser Jeff Law. “It just says a place of religious worship. And that’s about all it says. How do you define religious worship?”

McLennan County’s appraiser, Bobbitt, said he initially questioned the Global Prayer and Empowerment Center, a Waco ministry that sought a parsonage tax break for a home appraised at $682,000 on 0.4 acres in the organization’s name: Did a faith group that met in a movie theater really qualify for a tax-free clergy home?

“I thought, ‘Is this really a church service?’” he recalled. “But the law doesn’t distinguish.” So he approved the tax break, worth $17,000 a year. The church did not respond to phone and email messages.

In Galveston County, Strong Tower Ministries advertises itself as a residential treatment center for addiction, promoting detox through prayer, spiritual counseling, Bible study and physical labor such as making wooden crosses the organization sells. In its application to the Galveston Central Appraisal District to avoid having a tax bill on its $1.8 million 0.2-acre waterfront residence and boat house on Tiki Island, Strong said it also was a church that held regular worship services and employed staff pastors.

Its parsonage exemption, approved in 2019, relieved Strong Tower Ministries from paying $41,000 a year to the local school district and city and county governments. The property was returned to the tax-paying rolls two months ago when it was sold.

Texas lawmakers’ decision to leave “clergy” undefined also gives appraisers little leverage to scrutinize that portion of the parsonage application. In Webb County, the Catholic Dioceses of Laredo pays no taxes on a $625,000 residence “used to house the school sisters of Notre Dame” — teachers — according to the church’s application.

In Harris County, members of the Consecrated Women of Christ, a lay-member part of the Catholic group Regnum Christi, live on a tax-free 5-acre Spring property (including a 1.6-acre clergy residence) valued at $1.54 million featuring an elevator, pool and two ponds. “We embrace evangelical poverty, obedience and chastity,” the organization states on its website.

And appraisers wanting to determine if property owned by a religious group is “reasonably necessary” to its worship will find little guidance in the Texas statute. Brusniak, the property tax attorney, said the definition encompasses anything that could contribute to members’ spirituality, including a sports field, stations of the cross or a meditative trail.

In East Texas, Hunt County chief appraiser South said he has granted a growing number of 100-percent religious property tax breaks on corrals, pastures and barns — all considered reasonably necessary for so-called cowboy churches.

Last year, San Antonio’s Freedom Hill Church asked the Bexar appraisers to exempt it from all property taxes on vacant land next to the church. The property was “reasonably necessary” to Freedom Hill’s worship thanks to a new competitive BMX bicycle track, the church said.

“The BMX community did not have a place to ride so we wanted to meet that need to show the love of Christ to this community of people,” its exemption application stated. The BMX religious tax break helped erase part of the church’s $86,000 annual tax bill for its property.

More than the legal limit

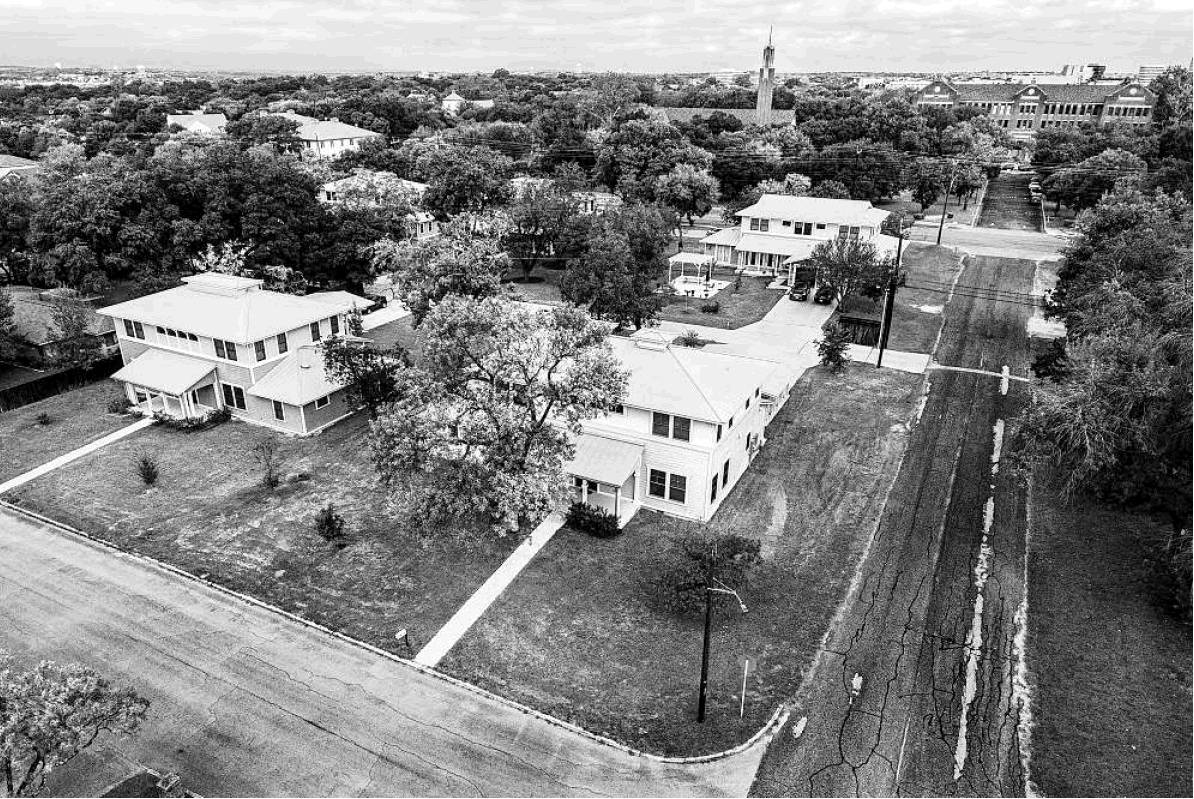

On a well-tended street in north San Antonio, a modern 3,500-square-foot clergy home owned by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a Roman Catholic order, pays no taxes. Nor does the nearly identical house next to it.

Or the house next to that. Or the two houses behind it.

In all, the Oblates’ six clergy residences occupy more than half a block across the street from the sprawling Oblate seminary. About 3.5 miles south, on prestigious Kings Highway, the organization also owns a tax-exempt 8,000-square-foot historic brick mansion worth $1.4 million.

The parsonages erase more than $110,000 in taxes that could help pay for San Antonio schools and local flood control, health system and community college districts. A spokeswoman said the homes are used for theology school students and their teachers.

“The code is too vague, too generous. Too ripe for abuse.”

McLennan County Chief Appraiser Joe Don Bobbitt, on Texas’ parsonage law

New Jersey limits churches to two tax-free parsonages. Tennessee allows one. Texas’ law has no limit.

Most churches own only a single clergy residence. However, a handful have taken advantage of the state’s porous statute to escape property taxes on multiple homes.

In one of Dallas’ toniest neighborhoods, Highland Park Presbyterian Church alone boasted 11 clergy residences at the start of the year, worth at least $15 million.

Gospel for Asia, which conducts missionary work, had at least 80 single-family residences in Kaufman County exempted as clergy residences before returning them to the rolls in a 2019 lawsuit settlement, said Sarah Curtis, chief appraiser for the appraisal district.

“The tax code doesn’t say anything specific — it just says parsonage for clergy,” she said. “It actually doesn’t even say how many.”

In more than 30 instances across the state, the Chronicle also found appraisal districts permitted religious organizations to exceed even the statutory 1-acre limitation on single parsonage properties.

North of Dallas, Denton County appraisers improperly allowed a 100-percent tax break on the Denton Baptist Temple’s 2.5-acre parsonage since at least 1992 — even though the church itself disclosed the excessive acreage on its application.

The chief appraiser said he has begun the process of notifying the taxpayer, who “ultimately will receive a tax bill for the unexempt amount,” the district said. Denton Baptist Temple did not respond to phone and email messages.

Lacking authority

Several appraisers said any rigorous religious exemption oversight they might apply was hampered by archaic equipment. In Webb County, Chief Appraiser Peter Gonzales said old software meant he was unable even to identify the tax-free parsonages on his South Texas county’s roll, never mind examining which of them might or might not qualify.

“Sorry for the confusion and inconvenience,” he wrote.

In Nueces County, the $1.12 million tax-free beachfront clergy residence owned by the Diocese of Corpus Christi sits on 1.14 acres — over the legal limit for a parsonage. Kristi Hill, the appraisal district’s taxpayer services manager, said the agency lacked the technical capability to separate it into a single-acre tax-exempt portion and a tax-paying segment for the remainder.

Others said soaring workloads meant triaging their attention. Appeals and protests have grown sharply in many locations. Yet appraisal districts still must meet the same tight deadline, certifying their entire tax roll within a year.

“Exemptions are a minutiae of the total trillions of dollars on the roll. And there’s a lot more offensive stuff happening than exemptions,” said Bexar County’s Amezquita, citing inequity between commercial and residential appraisals. “And because I’m going to have $27 billion in litigation anyway, I’m not really looking for more.”

Challenging a religious organization, in particular, is far down many appraisers’ list of priorities.

“It’s not a great way to operate, especially in this state,” said Bobbitt, who oversees valuing property in a county home to both Baptist-affiliated Baylor University and the Branch Davidians. “It’s not a fight you want to pick.”

Even for those willing to lock horns with churches over property taxes, appraisers say they often lack any legal authority to conduct investigations.

Sitting on 1.2 acres, the Family Vision Center’s karate church property would not qualify under the state’s 1-acre parsonage limitation. In its application, however, the center said 80 percent of the property was used for religious worship — entitled to its own tax break — and only 20 percent of the parcel and its nearly 6,000-square-foot home was used as a clergy residence.

Bexar County appraisers said that with no legal endorsement to inspect the premises, they accept such declarations on the honor system.

“We have no policing authority,” said Rogelio Sandoval, assistant chief appraiser.

Pastor Ivan Ujueta stressed that Family Vision met all the legal criteria for its parsonage and religious exemptions.

Yet the Chronicle’s examination also found that some appraisers failed to apply even the little leverage the state’s parsonage law permits. Many, for example, didn’t bother asking applicants who would live in the clergy residence, parsonage applications showed.

And although the law doesn’t require faith groups to resubmit exemption applications for periodic review, appraisal districts can ask them to. While some exercised the authority — Dallas requires religious organizations to reapply annually — others had conducted no review of the clergy tax breaks for decades.

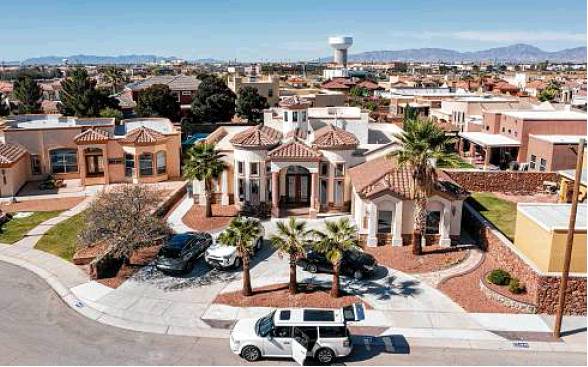

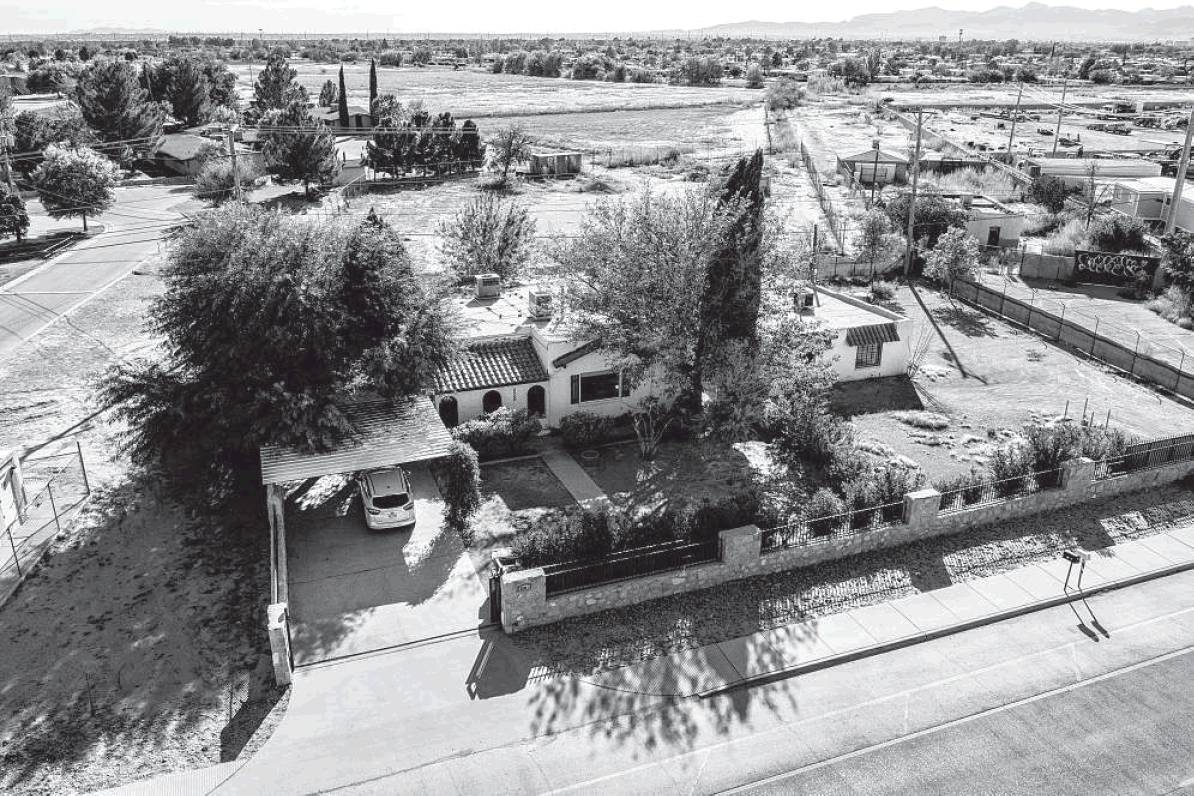

So much time had expired since Travis County reviewed many of its parsonages that their applications had long since been lost or destroyed. The last time appraisers in El Paso County asked the Catholic Diocese for an application on its parsonage on North Loop Drive was in 1992. A review might have revealed the 1.25-acre property appeared over the limit.

The Catholic Diocese in El Paso said it considered the parsonage to be two residences but acknowledged it was a single undivided tract with just one clergy member living there. El Paso Chief Appraiser Dinah Kilgore said she would “research” the property to see if any action needed to be taken.

But she said that once a parsonage is deemed exempt, the religious organization typically is not asked to reapply.

“We take their word for it,” she said.

A hands-off approach can cost taxpayers. In Tarrant County, the Bonds Ranch Homeowners Association earlier this year alerted appraisers that Dido United Methodist Church’s 2,300-square-foot parsonage had been rented out for the past five years, apparently violating the law’s requirement that religious organizations not earn money on their tax-free clergy homes.

“This is not fair to the other homeowners in our subdivision nor other residents of Tarrant County who pay their fair share of homeowner property taxes,” the association wrote.

After receiving the letter, the appraisal district confirmed the property didn’t qualify for the tax break. Dido’s parsonage was returned to the taxable property rolls back to 2018. The homeowners association did not return phone calls and emails. The church declined comment.

Presented with the Chronicle’s findings, appraisers in Bell, Bexar, Cameron, Chambers, Collin, Dallas, Denton, El Paso, Fort Bend, McLennan, Montgomery, Nueces and Waller counties said they would move to re-examine or restore back to the tax rolls religious properties that fell outside the law, most for being parsonages larger than 1 acre.

According to state law, the appraisal districts must move to recover up to five years’ worth of money due taxpayers. But so-called claw-back efforts are “very, very unpopular,” said Amezquita. Several appraisers said they were reluctant to pursue uncollected money from years past.

Bobbitt, in McLennan County, said he would start the process of moving excess parsonage property back on to the tax-paying rolls — the Chronicle identified two illegal clergy residences — but probably wouldn’t try to collect any back taxes.

“We’ve clawed back on some properties,” he said. “But not religions. Our thinking is that we should have caught it if it’s more than 1 acre. So I’m not going to penalize them.”

Chronicle research librarian Joyce

Lee contributed to this report. eric.dexheimer@chron.com jay.root@chron.com stephanie.lamm@chron.com