ENVIRONMENT

Project at Rice University tells story of Gulf Coast native prairie

Landscape architects seek to re-create endangered ecosystem in tiny plots on campus

By Diane Cowen STAFF WRITER • Melissa Phillip STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

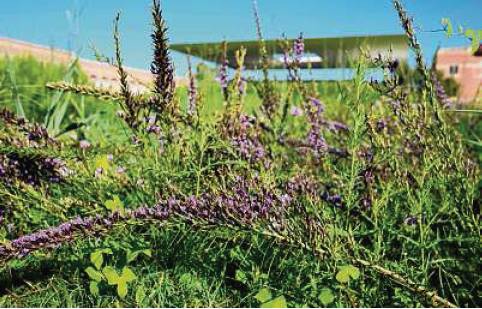

Stems of leggy Texas coneflower and hardy Indian blanket are among the late-summer remains of the 16 plots of native prairie that sit on Rice University’s campus, both a reminder of what once stood here and a hint of what still might be ahead.

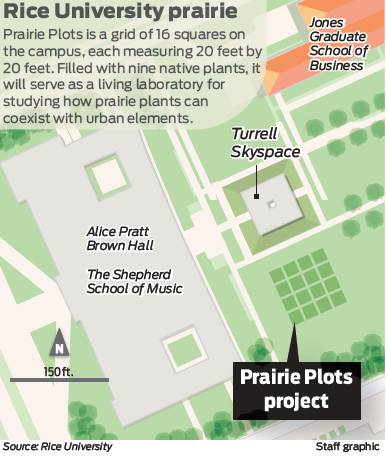

Landscape architects Maggie Tsang and Issac Stein recently walked through paths of freshly mowed turf between the plots of native plants that are part of their Prairie Plots project that introduced small doses of native prairie to students, faculty and visitors at the campus. Tsang is an assistant professor in Rice’s School of Architecture and Stein is her life/business partner at Dept., the landscape architecture and urban design studio they founded together.

The couple has lived in Houston a little over a year, but before they came, they researched the area’s historic ecology — Gulf Coast native prairie, now an endangered ecosystem. Two hundred years ago, miles of pristine native prairie ran from Lafayette in Louisiana to Brownsville in Texas. Residential and commercial growth, sprawling highways, overgrazing and invasive species have reduced the prairie to just 100 acres in Louisiana and 65,000 in Texas.

Not only did the native prairie plants feed insects, birds and other animal life, their deep root systems also soaked up rains during heavy weather events, making it a smart tool for flood mitigation today.

Tsang and Stein were inspired by Houston-area conservationists such as Mary Anne Piacentini, president and CEO of the Coastal Prairie Conservancy (formerly the Katy Coastal Prairie), which works to protect prairie land — even land that’s not pristine prairie — from further development.

At Rice, 16, 20-by-20-foot squares of prairie forming a grid at the base of the Turrell Skyspace near the Shepherd School of Music are heading into their fall season. Big and little blue-stem grasses shift into a purple-blue hue as bees buzz among the white poms of rattlesnake master.

The project began in March, when sod was removed to create the large squares. (The sod was transplanted elsewhere on campus.) Big cardboard pieces were put down to suppress weeds and turfgrass growth. Then, two planting events brought volunteers and master naturalists to put seeds and plants in the ground.

Some of the plants were “rescues,” scavenged from a site set to become a gas station and shopping area. There’s always a chance that other seeds or roots tag along with the native plants they wanted; wooly croton pops up in the squares every now and then. There are also plants such as bindweed — often called wild morning glory — that spring up, brought to the Prairie Plots by the wind or in bird droppings.

Tsang and Stein watched flowers grow through the spring and then tried to manage the summer drought. Now, visitors will still see flowers, though many have shed their petals, leaving only woody stems or leaves behind. By winter, it will be dormant brown squares waiting for their revival next spring.

The couple knows their plots aren’t pristine re-creations of prairie, with everything that might have been found by the animals and people who lived off of the prairie when Texas was still fairly wild frontier. Instead, they included nine species of native plants: Texas coneflower (rudbeckia texana), rattlesnake master (eryngium yuccifolium), big bluestem grass (andropogon gerardii), little bluestem grass (schizachyrium scoparium), blazing star (liatris acidota), Indian blanket (gaillardia pulcella), buffalo grass (bouteloua dactyloides), frogfruit mix (verbenaceae) and blue grama (bouteloua gracilis).

“It’s important to emphasize that this is a hybrid space,” Tsang said. “It’s a living laboratory, and our intention was not to establish a native prairie but to give space to the prairie ecology with urban elements.”

That means the fight against common turf — a mix of St. Augustine and Bermuda grasses — is never ending, since even the tiniest bit of plant or root in a little bit of dirt can grow. Right now, Tsang and Stein are trying to “shade it out,” meaning they keep it covered by other plants so it won’t thrive.

The Prairie Plots project was funded with just $7,500 from Rice’s architecture school, plus a lot of labor from the school’s Facilities, Engineering and Planning Department, or the grounds crews. They did the heavy lifting of sod removal and continue mowing the paths along the grid of plots; in fact, the paths were established based on the width of the mower, to make their work a little easier.

The Coastal Prairie Conservancy donated plants and seeds, and Nature’s Way Resources in Conroe and MicroLife donated compost and fertilizer.

The project began without an end date, though that could always come. Tsang and Stein said this garden will be a work in progress, and they’ll keep it going as long as the university will allow it.

They chose their small parcel of land for the attention it would get from its proximity to the Turrell Skyspace, which draws off-campus visitors, but also because of its out-of-the-way location that’s not a prime spot for a new, future building, they said.

Stein said he hopes this project will inspire change, letting people see native plants that work well where there’s bare public ground or even in neighborhood landscapes.

“These plants are a win-win for homeowners. They require less maintenance and are part of the native ecology,” Tsang said.

Stein added that homeowners who don’t want landscaping that looks so natural or wild can always organize plants by height and maintain clean edges around plantings to make their gardens look more intentional and less like they just planted things and ignored them.

“Beyond the hot tips of landscape design, it is a cultural question. We need to expand our view of what’s beautiful and acceptable in a neighborhood. Grass mowed to within an inch of its life isn’t the only acceptable thing,” Tsang said. “Designing with nature is a different attitude from designing against nature or designing to control the landscape.” diane.cowen@chron.com