FLOOD CONTROL

HOUSTON EYEING OWN TUNNEL VISION

San Antonio’s stormwater system offers a case study for Bayou City engineers looking to build bigger, bolder

By Emily Foxhall STAFF WRITER

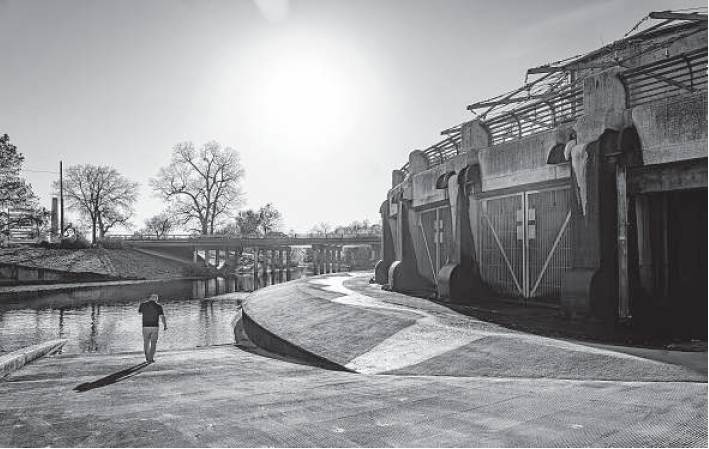

SAN ANTONIO — Standing in a small park at the corner of West Josephine and River Road in this three-century-old city, one can hear the stormwater system that officials believe saved their historic downtown. It’s the muffled roar of water plummeting 150 feet through a cylinder straight below ground.

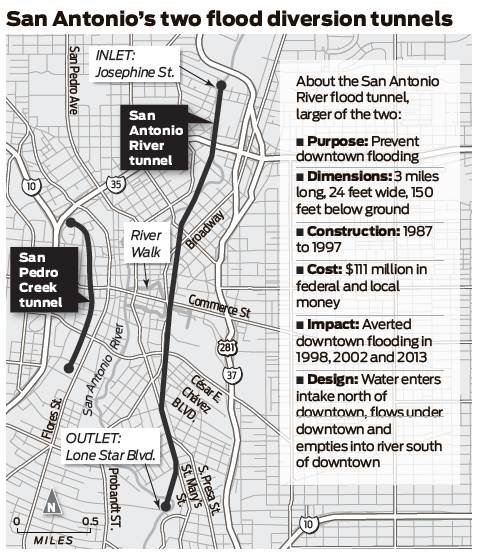

This is the start of the San Antonio River tunnel, which measures 24 feet in diameter and flows beneath the city center for a little more than three miles. Authorities think it’s among the oldest such tunnels in the country, though many don’t know it’s there.

“Don’t jump too much,” Nefi Garza, assistant director of public works, joked to a Chronicle reporter standing unknowingly on its concrete cover.

The tunnel provides a case study for Houston engineers analyzing whether to build something similar to protect the nation’s fourth-largest city. The region’s flood control infrastructure fell far short when Hurricane Harvey hit in 2017, causing deadly, catastrophic flooding and portending the stronger, wetter storms that climate change is expected to bring.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is studying whether a tunnel could help lessen flooding around Barker and Ad-dicks reservoirs, which Harvey put to the test, and along Buffalo Bayou. The Harris County Flood Control District is looking more broadly at whether a network of tunnels could help across the region.

Tunnels are a novel notion for the flat, swampy Bayou City, but supporters say the concept meets the needs of a built-out place with little room left for other flood control measures, such as wider channels or added reservoirs. And they point out that the technology has been tested: Austin has a flood tunnel. Dallas is building one. San Antonio has operated its tunnel for more than 20 years.

“We’re basically the last major (Texas) city without stormwater tunnels,” said Scott Elmer, assistant director of operations for the Harris County Flood Control District.

But Houston-area engineers are taking what’s been done and re-imagining it even bigger. The Corps’ proposed tunnel from Barker and Addicks reservoirs could stretch perhaps 35 miles out to Galveston Bay, costing billions. They’re trying to figure out if it makes economic sense. The Harris County vision could include tunnels across different parts of the area, also costly. They’re puzzling through where they could be placed.

Other concerns center around water quality: If water stays too long underground, it can lose oxygen, killing fish and other marine life when it empties into the Houston Ship Channel or Galveston Bay. And in Houston there are fault lines to consider. What can practically be done remains to be seen; San Antonio offers some insight into how ambitious the endeavor might be.

How it works

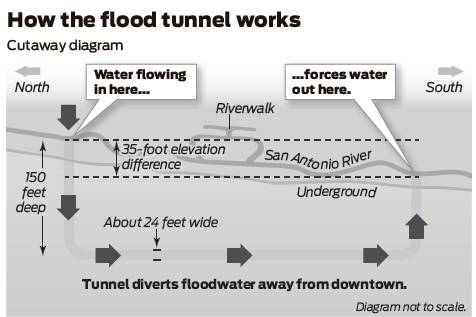

Here’s how the San Antonio system works: When a raindrop falls upstream of downtown, it flows with other stormwater into Olmos Creek. That waterway winds through a normally dry, forested park until it pushes through one of two open gates at the towering, concrete Olmos Dam.

Unlike the gates on the Ad-dicks and Barker dams in western Harris County, those in San Antonio aren’t opened and closed. The Olmos Dam lets through a fixed maximum amount of water that flows toward the central part of town, passing the San Antonio Zoo, University of the Incarnate Word and Brackenridge Park Golf Course. It becomes the San Antonio River, winding toward the Historic Pearl district and a small park, decorated with water spouts.

Here, the river flows through a series of 12 massive, slanted grates. Cans and tennis balls slip through. Rakes fastened to giant bicycle chains scoop big debris onto a concrete structure, where someone waits to dump it into a trash pit.

The stormwater that passes through the grates turns sharply right, then drops 150 feet and flows horizontally, at a slight tilt, beneath the area that includes the Alamo. Gravity pulls it along. Ventilation shafts allow the water to “burp,” pushing out excess air.

At the tunnel’s end, which is some 35 feet lower in elevation than where it entered, water travels back up a vertical column. The water gushes into a concrete room, pushing open gates in another small park and back into the San Antonio River, which has been naturally reinforced to handle more water.

Employees can monitor every step, perhaps from a work room or a laptop. Their supervisor likens them to first responders. “We’re always on call,” explained Dave Carreon, a senior electronic technician.

But on a sunny day, water doesn’t flow out the other end. It stays near the brim, like a murky pool. Engineers leave the tunnel full but constantly recirculate the water in it to keep it oxygenated. They pump water back up to the river at the start and pull water back in at the end.

The water that isn’t in the tunnel flows down the San Antonio River and around the restaurant-lined River Walk. On Tuesday, people strolled in dappled light beneath trees, a mariachi band readied to play and barge drivers motored around, all perhaps unaware of what it took to have the peaceful water here.

Can it work here?

What may happen in Houston shares some similarities, including the big-picture aim: to protect urban communities from flooding.

Planners were studying the idea for a tunnel in San Antonio in the 1980s, said Steve Graham, assistant general manager for the San Antonio River Authority. Workers finished one in 1991, just on the western side of downtown, perhaps the nation’s first.

“It was extremely innovative for those days,” Graham said. “Now it’s become much, much more commonplace.”

The river authority and Army Corps then completed the San Antonio River Tunnel in 1997. The city faced a major storm 10 months later, and officials say the damage that was prevented instantly justified the $110-million cost of the second tunnel.

Efforts here stem from Hurricane Harvey. The Corps is focused on the Addicks and Barker dams, built in the 1940s to reduce flooding risks along Buffalo Bayou and the downtown area through which it passes en route to the Ship Channel. Thousands of homes and businesses above and downstream of the dams flooded during Harvey, leading to lawsuits by property owners that are ongoing.

Initially, the Corps preferred widening and deepening Buffalo Bayou or building a third reservoir on the Katy Prairie, but public pushback was so strong that it is now taking a second look at the tunnel idea. It is now reconsidering building a tunnel straight from the reservoirs to the Ship Channel, running south of the bayou’s path to Galveston Bay, at a cost of $6.5 billion to $12 billion.

County flood control engineers, meanwhile, sought to be innovative after the storm, Elmer said. They debated whether it was even possible to build tunnels in the soft earth in the Houston area, and whether they could move enough water to make a difference. In both cases, they decided yes. But they used only preexisting soil samples, which weren’t comprehensive. That analysis will be refined.

“We do believe that tunnels really have the ability to be transformational when it comes to flood risk reduction,” Elmer said.

The flood control engineers look to San Antonio as a case study. The two differ not just in their length. Harris County Flood Control is proposing tunnels much larger in diameter, maybe 35 or 45 feet.

And the flood control district is considering whether the tunnels could be emptied out with pumps between floods, unlike San Antonio’s, which stay full. They plan to study whether sediment buildup will be a problem; in San Antonio, it flushes out.

Engineers are also looking at whether water could be added along the way in Houston, a change from San Antonio. There is storm surge to consider, too. In Harris County, planners say water would come out 3 feet above the level that the severe storm surge from Hurricane Ike reached in 2008. Flap gates will keep water from coming back in.

A system of multiple tunnels potentially joining together in Harris County intrigued those in San Antonio, who were excitedly curious about whether the elevation here is steep enough to pull that off.

“Can it work?” Garza asked of Houston’s plan.

Probably so, he decided. It would just be complex. emily.foxhall@chron.com