Fifth Ward school shows how I-45 expansion could harm children

By Emily Foxhall STAFF WRITER

Principal Shawn Nickerson can see the highway connector from Bruce Elementary’s basketball court. Cars whiz by, spewing dangerous pollutants into the air. And if the proposed Interstate 45 expansion moves forward, Nicker-son fears the children will be at greater risk. Some already moved because their apartments were sold to make way.

Federal officials earlier this year paused the state’s planning efforts on a rebuild of I-45 and various highway connections because of concerns about how it could affect communities of color and low-income neighborhoods. Critics recently filed a federal complaint calling for greater scrutiny of those impacts.

Bruce Elementary serves as a striking example of the project’s potential harm, following a history of environmental injustice in Greater Fifth Ward. Houston ISD relocated the school in 2007 from a spot across from a lead-contaminated industrial site. It was put near the juncture of Interstates 69 and 10, northeast of downtown. Advocates say students had among the district’s higher asthma rates.

Some of the kids live in a Houston Housing Authority property across I-10, walking on a bridge over 10 lanes of traffic, never escaping the fumes. The city earlier sold the state another housing authority property where students live. Fifth Ward residents navigate too among train tracks, concrete batch plants and a rail yard contaminated with likely cancer-causing creosote, used to treat rail ties.

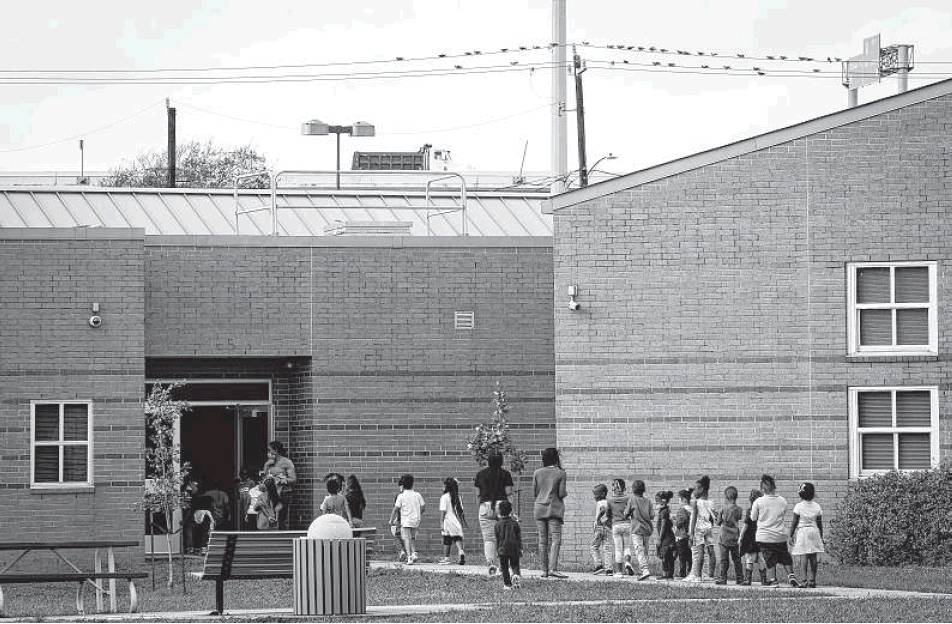

“Ms. Dr. Nickerson,” as students call her, can’t fix all that, but she considers it her job to advocate for better air quality and traffic safety. Her students play outside during recess. Some take puffs from inhalers at the nurse’s office beforehand.

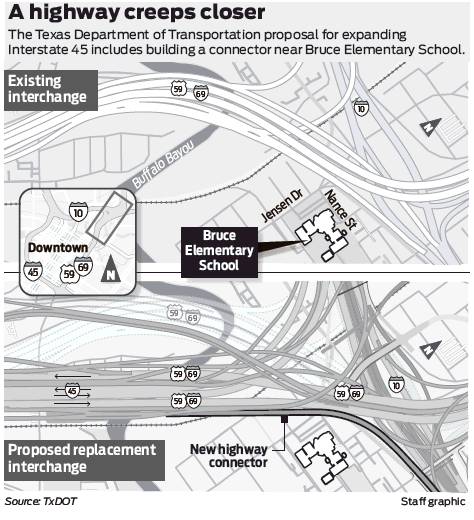

The $9 billion I-45 project, the largest freeway redo in Houston’s history, includes expansion work from central Houston all the way up to Beltway 8 in Greenspoint. It also reroutes the highway’s path around downtown. Instead of curling west as it does now, I-45 would circle to downtown’s east alongside I-69, until it meets I-10, right by Bruce Elementary.

A newly built interchange there would include a connector that would cut right by the northwest corner of the school, seeming to come as close as possible without actually taking any school property.

“Our students, when they go out to recess, what is that going to be like for them?” Nickerson asked. “What does that mean in terms of safety? Even beyond just outside, our indoor air quality, how will that change?”

Nickerson grew up in this area. Her grandma attended Bruce, founded in 1963. She also doesn’t want to see a reconstructed highway network take the sense of community away. Nickerson expects to lose about 80 kids who are relocating this year.

The school district hasn’t taken an official stance on the project, nor did a spokesperson have further information on why the campus was relocated by the highway. Harris County, which sued to stop the controversial project, paused its suit in order to work with the Texas Department of Transportation on potential solutions.

TxDOT leaders argue that the project will bring improvements to overall air quality. (Others question this.) Spokesperson Raquelle Lewis wrote that the agency considered community input and incorporated suggestions into the plan. The goal was “to build a project that will meet the needs of the community,” she wrote.

Victor Bennett, 59, sitting on a picnic bench waiting for school to dismiss, thought it would be good to have less traffic building up.

But 49-year-old Terence Callis, waiting in his Chevy Tahoe, said authorities weren’t listening to the community. He didn’t think residents had a chance to fight, because they lacked resources. Callis was among those who moved from the now-sold housing community, Clayton Homes.

Callis now drives about 25 minutes to pick up a first grader.

“We can’t beat TxDOT,” Callis said. “It’s a lost cause.”

The president of the school’s parent-teacher organization also is concerned about air quality and traffic safety, as well as the lack of information that she says parents received. Joetta Stevenson, president of the Greater Fifth Ward Super Neighborhood, said it felt like business as usual to be treated as if they wouldn’t speak out.

Lewis wrote in a statement that TxDOT reached out to parents about three or more years ago; she noted that its recent actions have been limited while the project is on pause.

Concerned about various impacts, Air Alliance Houston in 2019 helped coordinate an assessment of how schools could be affected. The environmental advocacy group looked specifically at nine schools, including Bruce. Researchers noted that children were especially vulnerable because their bodies are still developing.

Traffic-related air pollution can cause asthma to develop, the report says. Poor air quality could affect their day-to-day lives, perhaps causing missed school days from being sick and lower academic performance.

Advocates at the time suggested TxDOT build tree-lined buffers, install air monitors and not allow vehicles to idle in the carpool line. But then the argument around the project grew so large that detailed requests got lost, said Harrison Humphreys, an advocate Air Alliance Houston.

The school’s bell rang, and kids filed out. They passed through cheery hallways with prompts such as: “How can you make someone smile today?” Some met waiting relatives outside the back fence to walk home; others ambled home on their own.

Staff pointed the students away from the highway, sending them on a set route where crossing guards waited at each intersection to get them safely across the busy roads. emily.foxhall@chron.com twitter.com/emfoxhall