‘We were in the vanguard’

Westport Museum hosts first women admitted to Yale University

By Katrina Koerting

WESTPORT — Connie Royster grew up around Yale University. Her grandfather was a chef for Skull and Bones, a secret society at Yale, and other relatives cooked for fraternities and other places on campus.

Although she had attended functions on campus since she was a toddler and grew up in New Haven, as a female student in the 1960s, she never imagined she would attend as a student. Yale was closed to women until 1969, when the first female undergraduates were admitted and 575 started that fall.

Royster was among them, transferring to Yale her sophomore year from Wheaton College in Norton, Mass., a one-time all-girls school.

“When I got to Yale, I was ready to take it on,” Royster said at a talk at the Westport Museum for History and Culture on that first class of women.

Yale had a quota on the number of women it would accept when it went co-ed, meaning 13 percent of the student body was female, said Anne Perkins, author of “Yale Needs Women,” a focal point of Thursday’s talk.

Andrea DaRif, was at Staples High School when the announcement was made Yale would accept women, but it wasn’t clear until very late in the application process if high school students would be accepted.

“I immediately rushed in my application and crossed my fingers,” DaRif said at the talk. “I was lucky enough to get in.”

Both recalled what it was like to be among a small group of women on a predominantly male campus, something that was especially apparent when DaRif and her three roommates signed up for classes on one of the first days.

“We walked to register and saw a sea of guys and said, ‘OK, this is what we got ourselves into,’ and jumped right in,” she said.

But Yale was undergoing a larger identity transition at that time. It began shifting from the prep school feeder system it had been using, accepting more students of color and students from public schools, making that 1969 class even more diverse. Even so, Royster was only one of eight black women in the whole sophomore class and it had even fewer Latino or Asian students, Perkins said.

“My male classmates were sometimes as nervous as I was,” DaRif said. “This was a different environment. If they came from a rural high school, Yale was like the moon.”

Both said they felt supported at Yale, crediting some of that to the arts programs they were in, which they said tended to be more accepting in general and already had a history of women in the graduate program. Extracurricular activities were available to women.

The experience instilled more confidence in them and helped open doors after graduation.

“I wasn’t afraid to speak my mind and express myself because that’s what I had been doing since I was 18 years old,” DaRif said, adding being the only women presenting in a lecture hall of 100 men was more intimidating than any board room she entered later in life.

Their time outside of the classroom had its own battles though, as they and others, especially Elga Wasserman, special assistant to the president for the education of women, fought for things the female students needed on campus. It included security, broadening health access including contraceptives and gynecological care and even allowing more women to attend.

“She was the strongest woman we knew,” Royster said of Wasserman, adding there weren’t any female heads of colleges or deans when they started.

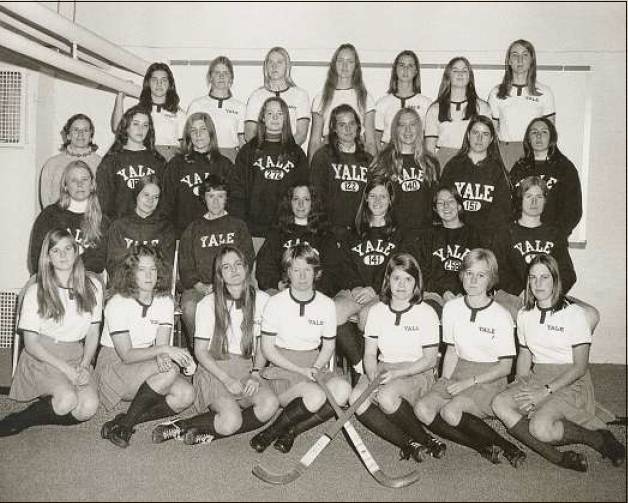

DaRif remembered how one of her friends and teammates, Lawrie Mifflin, essentially started the field hockey program at Yale. She had been a standout player in high school and looked to sign up for Yale’s field hockey team but was told there wasn’t one, nor any organized sports for women.

“She said, ‘Well that’s not acceptable. How do we start one?’ ” DaRif said.

Mifflin then went to the athletic director and eventually recruited the team to show there was an interest. With a team assembled, she went back to the office and asked about a schedule, but the officials said they weren’t sure what to do. Mifflin then spent the summer reaching out to schools to see if they would play them, crafting the schedule.

When they returned, they were able to have a club team before having a varsity team in place DaRif’s senior year. They eventually had the university get them uniforms and equipment, like they would for the men’s teams, but it wasn’t without some possible embarrassment first, DaRif said.

The team had been playing in t-shirts they all purchased at the co-op and cut off jeans. But when a photo came out of the Princeton team — their upcoming opponents — in nice kilts in the school colors, Yale officials called another another Connecticut school to borrow their powder blue kilts for the game.

“At first, we said we’re not going to wear them because they’re not Yale blue,” DaRif recalled, adding the university bought them kilts the next year.

Royster said students advocated for many things while at Yale, including civil rights and for an end to the Vietnam War.

The May Day protests over Bobby Seale and the Black Panther trials canceled classes and shut down the campus. Even the National Guard was called in. Royster helped organize a performance so that people could express themselves through art.

“It was a civics lesson on the ground,” Royster said.

Perkins said Royster’s roommate and other Yale women were influential in the case, Women v. Connecticut, that overturned Connecticut’s abortion ban before Roe v. Wade.

Their advancements and civic engagement feel especially poignant now 50 or so years later following last week’s overturn of Roe.

“We felt so hopeful,” DaRif said. “We felt we were in the vanguard of proving we should have equal rights, equal protection under the law. We felt we were successful proving to people we weren’t simply second class citizens.”

When DaRif and Royster started college, women were still not allowed to have credit cards in their own names. They needed husbands, she said.

“The strides we made over the last 50 years felt very heartening and this felt like a punch in the gut,” DaRif said.

Royster said it feels like they’ve turned the clock back, but the struggle continues.

“It’s deja vu but we have to fight,” she said. “We have no choice.”

Royster said few people experienced what they did and so those bonds formed at Yale are some of the most important relationships in her life. She still has a monthly Zoom meeting with her fellow 1972 alumnae.

She even went to a women’s march with some of them.

“We’re getting older but we can still march and protest and we still have to,” Royster said.