BASEBALL

In 1959, he was almost perfect

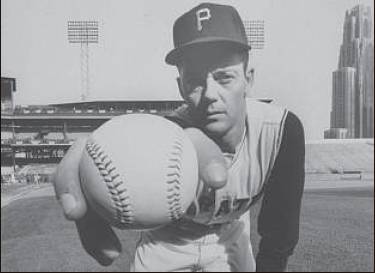

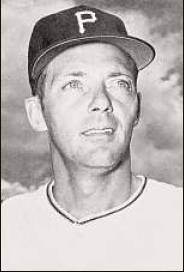

Historic year for Stephentown’s Elroy Face didn’t land him in Hall of Fame, but it’s 1960 that irks him

By Abigail Rubel

Ian Anderson wasn’t the first Capital Region pitcher to make it in the big leagues, only the most recent. Thirty-nine years before Anderson was born, Stephentown’s Elroy Face won 18 games in relief for the Pittsburgh Pirates and lost only one, setting a record that stands today. In his 16-year career, mostly with Pittsburgh, Face, now 94, also picked up 22 consecutive victories (starting at the end of the 1958 season and stretching into 1959), which was still the record for longest winning streak by any kind of pitcher when he retired in 1969.

Known as “the Baron of the Bullpen,” Face also retired with the record for career games won by a reliever (104), and he was the first pitcher to record three saves in a single World Series, helping the Pirates upset the Yankees in 1960.

Despite his many achievements, he’s not in the Hall of Fame. He spent the maximum of 15 years on the ballot, receiving a high of 18.9 percent of votes from Baseball Writers of America Association members in 1987.

“I think about it, but nothing I can do about it,” Face said from his home near Pittsburgh.

Growing up in a family of carpenters in Stephen-town, Face didn’t start pitching until he was 16 and attending Averill Park High School. He eventually caught the eye of a scout while playing for a pickup team in Lebanon.

“Had a couple good weeks, a couple strikeouts — 17 one week, 18 the other week. The scout saw it in the paper, and he came down to watch me pitch, and in the seventh inning signed me to a contract,” Face said.

The 5-foot-7, 153-pound right-hander was known for his forkball, a pitch similar to the split-finger fastball where the pitcher’s fingers are on either side of the ball.

Face still follows the Pirates (8-11 this season), though he has concerns about their bullpen.

“They need pitching. They can score runs, but they don’t hold the other team,” he said.

The Veterans Committee put Face up for a vote a few times, but he was unsuccessful there, too. He’s still eligible for consideration through the Classic Era committee, which meets again in 2024, but the odds of Face getting in at this point are low, according to MLB’s official historian, John Thorn.

“That’s because the nature of the relief pitcher has changed over time, and saves are the currency, and that was not what managers were looking for from relievers then,” Thorn said.

The save wasn’t adopted as an official MLB statistic until 1969, though it was used widely starting in 1959. A save is credited to a pitcher who finishes a game for the winning team under certain circumstances — commonly when a pitcher enters in the ninth inning in which his team is winning by three or fewer runs, and finishes the game by pitching one inning without losing the lead.

Statisticians have calculated saves for pre-1969 pitchers, and Face’s are nothing to sneeze at — he led the National League in 1958 (20 saves), 1961 (tied with Stu Miller with 17) and 1962 (28). He finished with 191 career saves. But his best statistic was wins, and by the time he was on the ballot in 1976, saves were seen as a more accurate measure of success for relievers.

Hoyt Wilhelm, the first reliever to get into the Hall of Fame in 1985, was the first pitcher to 200 saves, finishing with 228. Rollie Fingers, the next reliever in Cooperstown, had 341.

“(Face) just wasn’t quite used in the same way that really generated that sort of high visibility,” said Jay Jaffe, a BBWAA member who wrote “The Cooperstown Casebook” analyzing Hall of Fame players.

Face usually had to pitch multiple innings and wasn’t consistently used in save situations the way pitchers are today. Aroldis Chapman of the New York Yankees, for example, has 310 saves despite pitching 611 innings to Face’s 1,375.

John Perrotto, a longtime Pirates writer and member of the BBWAA, said he regularly struggles with how to approach relievers on the Hall of Fame ballot.

He once asked Trevor Hoffman, another Hall of Fame reliever, how to evaluate the position.

“He thought the benchmark in his eyes — and this is somebody who did it for a long time — is the number of 30-save seasons that they had,” Perrotto said.

But that standard doesn’t quite fit a reliever like Face, who pitched when the save was only gestating.

In Jaffe’s opinion, it’s hard to make the case today that Face belongs in the Hall of Fame from a statistical standpoint.

“But if you put Roy Face in the modern model where he’s only got to work one inning a day, he can throw a little bit harder and focus only on the games where he’s got a save chance, he might come out of it looking very different,” Jaffe said. “Then again, maybe not.”

When Face looks back on his career, it’s not the lack of a Hall of Fame plaque that bothers him most, though — it’s not winning the 1960 World Series MVP.

“I was the first closer to have three saves in a World Series, and if the Yankees hadn’t tied it up in the last game I’d have had the win in that game, and they gave the MVP to (Bobby) Richardson for the Yankees. That’s the only time in baseball that a losing player got the MVP,” Face said.

“Had a couple good weeks, a couple strikeouts — 17 one week, 18 the other week. The scout saw it in the paper, and he came down to watch me pitch, and in the seventh inning signed me to a contract.”

Elroy Face, former MLB pitcher from Stephentown