Pedestrian deaths on way to new high

City on pace to beat last year’s 61, the most in two decades; analysis shows problem roads in poorer areas

By Bruce Selcraig STAFF WRITER

As if Tomika Monterville needed further validation for San Antonio’s newly conceived transportation department that she was hired in February to run, the former urban planner now finds herself in a possible record-setting year for pedestrians killed by motor vehicles.

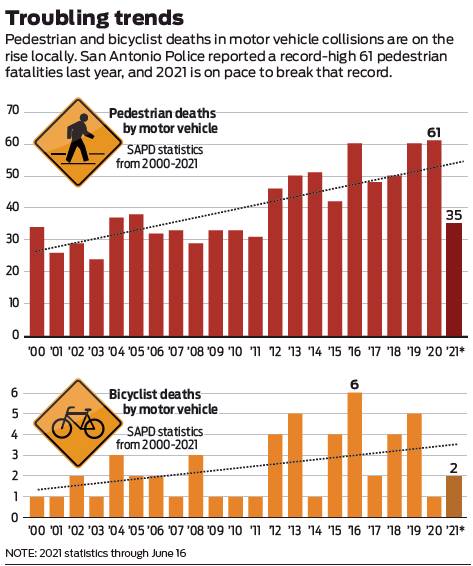

By mid-June, the city had already recorded 35 pedestrian deaths, a lethal pace that would exceed the one that produced last year’s total of 61, the highest recorded by the San Antonio Police Department in two decades. The city also has seen two fatal auto-cyclist accidents this year.

As always, across Texas and the nation, there are a host of proximate causes for auto-related deaths involving pedestrians and cyclists; excessive speed and drivers who are drunk, drugged or distracted are the most common.

“It’s a serious matter that must be addressed in a variety of ways. Enforcement of traffic laws is only a part of any possible remedy,” Police Chief William McManus said in an emailed statement.

An unmistakable, perhaps predictable, rise in bike and pedestrian deaths from 2000 to 2020 came as the city gained around 700,000 people. Monterville and traffic analysts like her have long believed the more general cause may simply be the primacy of automobiles in cities.

“We still prioritize the automobile to the detriment of all others not in an automobile,” Monterville said recently as she returned from a daily downtown walk for coffee. “We keep making the same excuses for why we can’t make people safer.”

Unfortunately, San Antonio’s experience may be part of a national trend.

According to data analyzed by the nonprofit Governors Highway Safety Association, the first six months of 2020 saw a 20 percent increase in U.S. pedestrian deaths over 2019, when calculated as a rate per vehicle miles traveled. Pedestrian deaths increased by about 46 percent in the decade after 2009, fueled by dramatic rises in accidents involving SUVs and nighttime collisions.

“Thirty-five deaths is simply the cost of doing business in a car-dependent society,” Bill Fulton, director of the Kinder Institute at Rice University in Houston, said of San Antonio’s deadly pace this year. “Having thousands of deaths each year that are preventable is indeed a public health crisis.”

June has been especially bad.

On June 10, shortly after 9 a.m., a speeding car on Culebra veered into oncoming traffic, jumped the curb and killed a woman sitting at a bus stop. That location has been deemed so dangerous that in 2016 the Texas Department of Transportation installed a $100,000 raised pedestrian island with safety beacons.

The woman at the wheel was charged with intoxication manslaughter.

The next night, a 37-year-old man was killed by a hit-and-run SUV as he crossed Castroville Road on the West Side in an area police said was poorly lighted and had no crosswalk.

On June 15, about 3:30 p.m. in the 1400 block of Vance Jackson, a man who had an unknown injury and was driving himself to a clinic passed out and fatally struck a pedestrian at another bus stop. The driver died the next day.

An analysis by the San Antonio Express-News, using SAPD statistics, shows that many of the city’s most dangerous streets run through or near poorer neighborhoods and have remained lethal corridors for many years.

From 2011 to June of this year, a 2.2-mile stretch of Culebra between General McMullen and Interstate 10 has seen 17 deaths of pedestrians and cyclists; Austin Highway between Walzem and North Vandiver (2.6 miles) had 14 deaths; Enrique Barrera Parkway between South San Joaquin and South Acme (1.8 miles) had 11, and a mere half-mile stretch of Fredericksburg from the South Texas Medical Center to Datapoint had five.

On Bandera, from its start at Culebra northwest to Hillcrest, there have been seven pedestrian deaths just since January 2020.

Several intersections have seen at least three pedestrian deaths since 2011: General McMullen at Ceralvo, General McMullen at West Commerce, Culebra at Bandera, Culebra at Zarzamora and Nacogdoches at Village Square.

The most dangerous roads are usually five- or seven-lane traffic arteries with a faded yellow-striped turn lane in the middle.

“Many of them are state highways maintained by TxDOT,” Fulton observed, “and their engineers are totally focused on moving vehicles and nothing else.”

Monterville has noticed that, unlike in Florida, where she has worked, and Southern California, where she grew up, San Antonio’s major corridors rarely have the raised grassy medians in the middle that separate traffic and offer a refuge for pedestrians jaywalking hundreds of yards from the nearest crosswalk.

TxDOT spokeswoman Laura Lopez said the agency has spent about $28 million on sidewalk infrastructure in San Antonio since 2018 and has several current and future “raised median” projects that will improve the safety of roads such as Culebra, S.W. Military, Bandera, Austin Highway and Fredericksburg, among oth-“Calling a road dangerous,” she added, “is not usually the case.”

On these roads and others, at almost any hour of the day, people can be seen darting between waves of vehicles, sometimes holding children or groceries. Or they are nervously stuck in the middle, heads on a swivel, hoping that speeding cars so close they could touch them somehow don’t.

“Many of those people who get killed (crossing busy streets) do not have enough money to buy a car, and they have been pushed farther and farther from the inner city, away from public transit, so this problem is only getting worse and it is moving into the suburbs,” Fulton said.

Monterville is not looking to blame TxDOT, city planners, reckless drivers or the thousands of cyclists and walkers who don’t always obey the law or wear bright reflective clothing at night.

“Yes, we can reduce speed in so many places, but we also have to go back to the drawing board in the design of our roadways. We have to design them physically and visually to slow them down,” she said. “We don’t really often see pedestrians or cyclists being the ones at fault in these accidents.”

Danger to bicycles

One of her first jobs, Monterville says, will be to update the city’s 2011 bicycle master plan, but she’s also aware that many in the biking community are weary of what they see as a “plan, plan, plan” mentality at City Hall and want immediate progress in the construction of well-conceived protected bike lanes.

Some streets, she says, are simply too dangerous for anything other than a fully protected bike lane physically separated from auto traffic by concrete planters, Jersey barriers or at least a curb, not just painted white lines.

Asked if a cyclist would be foolish to ride, say, Broadway, seven lanes at its widest, with dozens of commercial entrances, Monterville diplomatically said they would certainly be “brave.”

“We have to work on those corridors,” she said. “When I look at our bike infrastructure, it is all over the place. There is no system. There is no network. Cars have a network. But we can’t keep putting cyclists into a system that is unsafe.”

Monterville was working in Washington, D.C., when, in 2008, she struck a cyclist with her car on Thanksgiving eve as she made a right turn from a dedicated turn lane.

“I looked in my rearview and sideview mirrors,” she recalled, “and he was in that blind spot where the frame meets the windows, and I hit his rear tire. Fortunately, he didn’t have a severe injury.”

Her lesson was that many cyclists try to jump ahead of turning vehicles at a stop light and you have to look for them directly. Having a motorcycle license has given her yet another perspective on two-wheeled vulnerability — and invisibility.

Comfortable in the planner-speak of her world, Monterville offers the familiar catchphrase of traffic therapists, that it will take “education, engineering and enforcement” to make streets safer.

Her first months have been filled with hiring a staff of nine, studying traffic and reaching out to people such as Bryan Martin, founder of electric bike startup Bronko Bikes and director of the city’s largest cyclist organization, Bike San Antonio.

“We have a good rapport with Tomika,” Martin said. “We welcomed her to the city and talk with her often.”

Not one to mince words, Martin said San Antonio is10 years behind Austin and 20 years behind Washington, D.C., in terms of retrofitting its streets to accommodate cyclists.

He often rides his electric bike in a full slow lane going about 30 mph from his home near MacArthur High School on the Northeast Side, down the Salado Creek Greenway to Austin Highway, maybe a jog on Wiltshire, then treacherous Broadway all the way downtown, some 12 miles, to make a City Council meeting or sit in on a transportation committee hearing.

“The city and state need to stop thinking of cars. The romance of cars is over,” Martin said. “It’s a shame that visitors see Broadway. It could be the showpiece of a progressive city. Our amazing Síclovía event (an annual spring celebration of bikes and street life) could be every day if we had protected bike lanes on corridors.”

Of all the local streets ripe for remodeling, Martin would pick Roosevelt as his first priority, “because it is the heart of culture for this city, takes you to all the missions and is a corridor into downtown.”

Restaurants and bars need to crack down on drunks, he says, and SAPD must step up enforcement.

Yet the first thing Martin wants Monterville to tackle is hearts and minds, with perhaps a 60-second public service announcement for TV viewers of people showing respect for each other on the road.

“I’d call it, ‘Home Safe,’” he said. “And maybe we’d have the mayor leaning out of a Suburban tipping his hat to a cyclist.”

Monterville “seems transparent and friendly, but she is just one person, with a small staff, and like other officials she will probably respond to those with the loudest voices,” Martin said. “That’s who we — cyclists, pedestrians — need to become.”

News researcher Misty Harris contributed to this report. bselcraig@express-news.net