CHRONICLE INVESTIGATION

Speed traps ahead

Safety, revenue collide in analysis of where police pulled over most motorists in Texas

By St. John Barned-Smith and Eric Dexheimer STAFF WRITERS

Pranav Chopra was headed down U.S. 59 to Houston when he saw the flashing lights in his rear-view mirror. He’d been speeding, a Corrigan police officer told him.

He’d been returning from a visit with his parents when he passed through the small Polk County town.

“I remember it going from 75 to 40 in a matter of seconds,” he recalled. “Someone was sitting right there.” After driving away with a nearly $200 ticket, he voiced his frustration in a tart Google review. “Nothing makes me more sick than a speed trap town. … Police get a bad reputation when they blatantly steal from the citizens.”

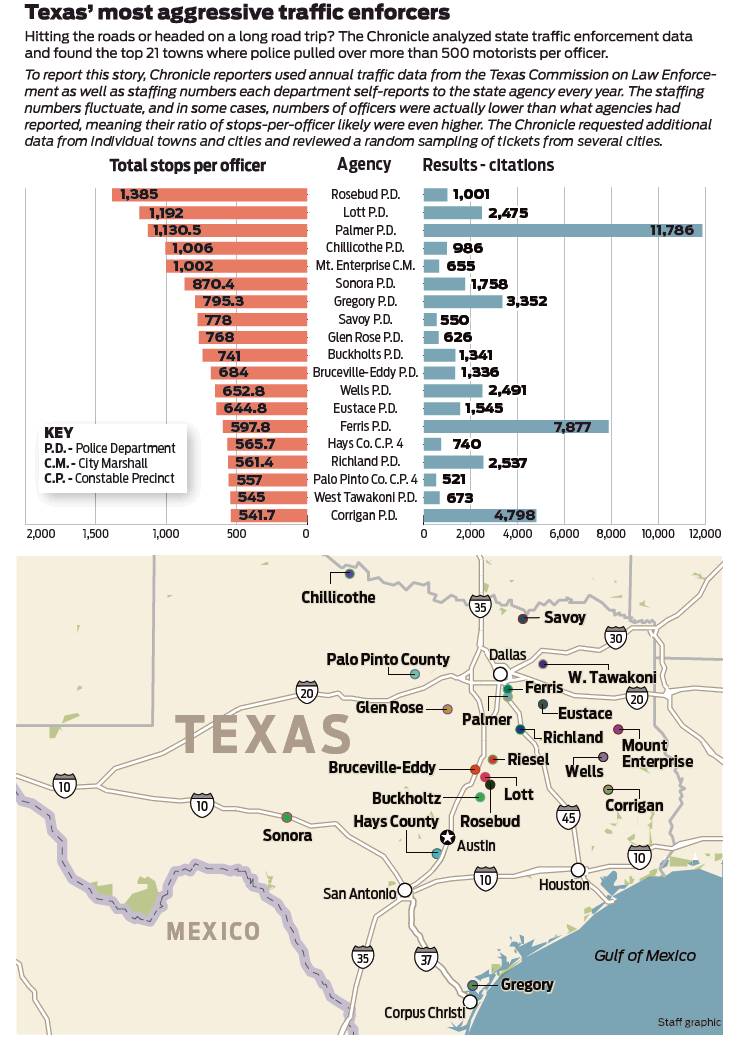

Chopra has had plenty of company. A Houston Chronicle analysis of traffic-stop data from Texas’ more than 2,500 police departments found Corrigan’s officers are among the most aggressive traffic enforcers in Texas. Last year, the town’s 12 police officers pulled over 8,100 motorists —more than 600 per officer. The Chronicle looked at the data and found the top 21 towns where police pulled over more than 500 motorists per officer.

No one is arguing that motorists stopped by the high-volume departments weren’t driving over the speed limit. Police in these jurisdictions say aggressive ticketing is a useful strategy to improve community safety on the road and off.

“If you take care of the little things like traffic, and you’re out in the community being seen, you don’t have as many big things,” said Riesel Police Chief Danny Krumnow, whose three-person department stopped an average of 530 motorists per officer in the McLennan County town.

Yet some, including even law enforcement veterans, are skeptical of such arguments.

“When you see everyone gets a ticket, that’s a problem,” said former Texas Department of Public Safety commander Patrick O’Burke.

Traffic fines often make up a substantial portion of the local government’s revenue. The city of Lott, south of Waco, recorded $651,251 in revenue from municipal court fines in 2020, according to its most recent annual budget. That was more than a third of its general fund.

Fallout from aggressive speed enforcement can be more than a burdensome ticket. Seeking contraband, many departments often use traffic stops to initiate vehicle searches — most of which turn up nothing — that can quickly transform a minor infraction into a confrontation. The Chronicle analyzed state data required by the Sandra Bland Act to identify which Texas police departments’ officers pulled over drivers the most. The law was named for Sandra Bland, who committed suicide in a Waller County Jail in 2015 after she was arrested following a minor traffic stop. Her death sparked an outcry and raised questions about police interactions with the public and how they can escalate into violence.

Ticket-per-officer stats

Speed traps have bedeviled drivers traversing Texas for decades. In the mid-1970s, the town of Selma (pop. 207), near San Antonio, became notorious for its zealous speeding enforcement , as officers issued hundreds of tickets every year, raking in more than $168,000 in fines.

Researchers have employed several methods to identify the state’s more aggressive ticket-writers. The Chronicle used traffic stop and ticketing numbers every department must submit to the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement as part of the Sandra Bland Act, passed in an effort to make police departments more accountable for their traffic stops. It divided each department’s stops by the number of sworn officers the agencies reported to TCOLE to produce a ticket-per-officer figure for each department.

The numbers may not always be perfectly precise. Traffic stop data is self-reported; TCOLE does not check it. The number of sworn officers can change as staff come and go. Yet many of the high-volume departments identified in the analysis have also appeared on other published lists.

“We’re no stranger to the public eye,” said Palmer Police Sgt. Joseph Garcia. “We do a lot of stops.”

Many of the state’s most aggressive traffic enforcers shared key characteristics: small towns situated on busy high-speed thoroughfares where the speed limit quickly drops from highway to local-street speeds — or even lower where school zones intersect roads. Virtually all of the departments had fewer than a dozen officers.

Fines as revenue

For some communities, the traffic fines are an integral part of the city’s budget, creating an implicit pressure to keep volume high. In Wells, in East Texas, the chief’s report at every city council meeting consists of a tally of traffic stops and tickets written.

In a 2019 study, Governing Magazine identified Texas as among the country’s top states with communities — small, rural cities, in particular — whose budgets depended heavily on collecting traffic fines. Texas law limits small cities from too much reliance on ticket revenue, yet enforcement of the statute is on the honor system and a legal loophole makes violations rare.

Another law makes it illegal for Texas police to be required to meet ticketing quotas. Yet officers in several departments have said recently they faced consequences if they didn’t cite enough drivers for traffic violations.

In Mount Enterprise, where the East Texas community’s single officer made about 1,000 stops last year, the $118,000 in collected fines comprised nearly a quarter of the city’s budget. The year before, the city collected only about a third of that after firing its lone police officer. He sued, saying he was terminated after alerting the Texas Rangers he’d been told he would lose his job if he didn’t meet traffic ticket quotas. In 2019, the city administrator was convicted of setting a traffic ticket quota and sentenced to six months probation and fined $2,000.

For some high-ticket volume departments, “It’s not about getting a driver to drive safely,” said O’Burke. “It’s about how much revenue they’re getting out of them.”

In Palmer, which sits along Interstate 45 south of Dallas, collected fines exceed property tax collections and made up 40 percent of its 2019-2020 general fund. City Administrator Alicia Baran acknowledged the money was important to the town’s bottom line, but added that it’s not a predictable revenue stream.

Lawmakers have tried to rein in the practice. Towns with populations less than 5,000 are prohibited from using radar on the state’s biggest highways. Municipalities that generate more than 20 percent of their annual revenue from speed enforcement must report their earnings to the state comptroller. If the proportion rises above 30 percent, the extra must be turned over to the state.

Yet the law is rarely invoked. Relying on municipalities to self-report gives them the opportunity to skirt the requirement, said Pat Monks, a founder and past president of Traffic Lawyers of Texas. “Unless the auditors are going to come in and the comptroller demands they turn additional revenue over — they are probably not going to do it,” he said.

The statute also is financially forgiving, allowing municipalities to count not only their general fund income, but also self-sustaining enterprise funds such as water and sewer. When that is added in, fine revenue makes up 27 percent of Palmer’s total income, just below the state’s 30 percent threshold.

Records from the comptroller’s office show that over the past five years, only four municipalities have been forced to return excess money collected from traffic fines.

Slower is safer

Corrigan, the object of Chopra’s ire, is about 95 miles northeast of Houston. It takes up 2.3 square miles of land, has a population of 2,300 and a police force of 12 officers and three administrators. With its three churches, doughnut shop, Mexican eatery, two burger joints and a cafe, and a sprinkling of other businesses, it is the kind of town that drivers whip past in minutes.

It should probably take longer. “People drive fast,” Chief Darrell Gibson said. He keeps a framed

Corrigan Times article in the lobby of his small department’s headquarters about the town’s traffic fatality rate, one of the highest in Texas.

“That’s why I designated a traffic safety officer,” he said. “To try to slow people down. Every time there was a traffic death, it was because they were going very fast.”

It’s a common refrain among small town chiefs and administrators of high-volume jurisdictions, who say they’re just trying to improve safety by slowing down drivers recklessly racing through their communities.

Some evidence suggests rigorous speeding enforcement can help save lives. Greg DeAngelo, an economics professor at Claremont Graduate University, analyzed the impact of a 2003 budget crisis in Oregon that led to 35 percent fewer state troopers patrolling state roads. He found the layoffs led to dramatically reduced citations that “strongly correlated” with a 17 percent rise in highway fatalities.

Skeptics say data in Texas over the past decade tells a different story. Scott Henson, researcher for the criminal justice nonprofit Just Liberty, argued that major population increases and miles driven over the past decade — coupled with radical reductions in police enforcement in recent years — have had no significant impact on crashes or fatalities.

“When traffic enforcement was reduced by more than half, we saw no increase in traffic fatalities — and even a slight decline in fatalities per mile driven,” he said. “I understand why (police) do it and believe it has that effect — but the data doesn’t show that.”

‘The chance to go bad’

Other critics say the negative impacts of overzealous traffic enforcement far outweighs any benefits police say they bring. “It leads to a lot of unnecessary interaction between police and the community that have the chance to go bad,” said Joanna Weiss, co-director of the Fines and Fees Justice Center. “It erodes community trust in law enforcement and makes it harder to address public safety issues.”

Municipalities that depend on ticket revenue for large chunks of their budgets also are relying on “a very regressive tax scheme” that disproportionately impacts poorer people, she added.

With fines and surcharges, a traffic ticket “often results in a lot of people in poverty getting stuck in this cycle of debt and jail and the inability to drive legally — often for years,” said Chris Harris of the nonprofit public interest justice center Texas Appleseed. That can lead to “an impossible choice” of not driving or driving with a suspended license, which can then result in criminal charges.

Several of the most active departments have gained notoriety for their traffic enforcement. Tenaha, a tiny East Texas community straddling Highway 59, was sued for using frequent traffic stops as a pretext to search vehicles — mainly driven by Black motorists — and confiscate money and property. In a settlement agreement, the town promised to stop the practice. In 2020, the department stopped 1,800 motorists, writing 1,100 tickets. Chief Scott Burkhalter, who is new to the job, said the department ranged from one to four officers during that time.

It doesn’t take many officers to affect a small city’s bottom line. Wells didn’t have an active police force in 2017 and collected less than $10,000 in fines. When it reactivated the department a year later, fine collections rose to $592,865.

Mount Enterprise City Secretary Suzanne Pharr noted the city’s collections were under the state’s 30 percent threshold. Ticket collections aren’t a “huge part,” of its budget, but acknowledged they help pay the salary of the town’s lone police officer.

“We want safety of our citizens to come first and foremost,” she said.

Others say departments whose officers can afford to spend so much time writing tickets signal a jurisdiction that is over-policed. “These are cops who don’t seem to have much police work to do,” said Henson, the researcher for Just Liberty.

In Gregory, a city of 2,000 across the bay from Corpus Christi whose officers are some of the state’s most prolific ticket-writers, Chief Tony Cano said there was some truth to that.

“Our number of call-outs is low, so I guess you could say they have more opportunity to work traffic,” he said. Although “officers are not encouraged to write tickets, that’s what they do. I’ve seen the numbers and I’m like, whoa, those are high.”

‘Don’t turn on your lights’

In Riesel, Krumnow is adamant: When his two officers aren’t working other calls, they better be working traffic. State data show about 87 percent of motorists stopped last year drove away with a ticket. Municipal court fines last year made up more than half of the town’s general fund.

For Krumnow, the issue is personal. In 2019, a speeding driver lost control of his vehicle, slid off the road and smashed into him while he was helping a McClennan County sheriff’s deputy on a traffic stop. The deputy died and Krumnow barely survived. It took more than a year of recovery before he was able to return to work.

He himself sometimes parks his department SUV just south of Rodriguez Tire Shop, clocking drivers as they come over a rise just south of town, where the speed drops from 75 to 55 miles per hour. On a recent weekday, he clocked cars passing through the outskirts of town 10 or 15 miles over the limit.

He said he encourages his officer to stop only those drivers speeding significantly faster than is legal. “Before you cut those lights on, you need to decide if that person needs a ticket,” he said. “And if they don’t, don’t turn your lights on.”

MORE ONLINE See which Texas agencies have stopped the most people per officer in 2020. houstonchronicle.com/speed