Legislature’s low pay a roadblock for many

Wage of $600 a month limits who can afford to serve in Capitol

By Jeremy Blackman AUSTIN BUREAU

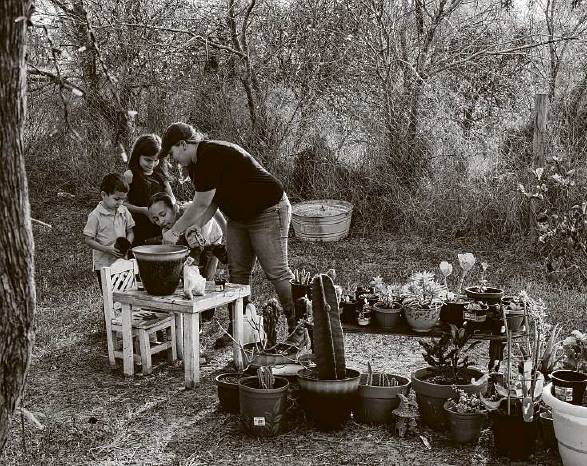

Alicia Caballero called in to the Sept. 15 meeting of the Texas Ethics Commission to ostensibly comment on a routine per diem adjustment for state legislators. But the 28-year-old mother of three really wanted to discuss something bigger.

“Our founders had a simple belief at the core of their ideology about governance: a government of the people, by the people, for the people,” she began. “These are words that the majority of us can recite by heart from a very young age. And yet, I would argue that our current legislative representation is a gross perversion of that ideal.”

“As it stands today, someone like me, an essential worker, even making more than double the minimum wage would most likely never have the opportunity to serve my fellow citizens through policymaking,” Caballero added. “No matter how much I may desire to, simple economics and archaic policies prevent it.”

She was talking about legislative pay.

For nearly five decades, elected officials in Texas have made the same paltry salary, $600 a month — hardly enough to sublet a room in Austin during the legislative session, let alone live on. Few states pay their representatives less, and in Texas, where lawmakers meet for five months every other year, it has become both a prized symbol of small government and a roadblock for many would-be candidates.

“It’s impossible for a public school teacher to serve, or a firefighter, a nurse, a police officer — really anybody with a normal job,” said Rep. James Talarico, D-Round Rock, a former teacher who now consults part time.

Caballero has been trying to change that. In September, she asked the Ethics Commission to raise legislative salaries to $36,000 a year, or a little less than what an average adult with a working partner and no children would need to survive financially, according to research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“By not providing a living wage for that position, we are irrefutably limiting the type and class of persons who can serve,” she told the commission. “It is the dreaded dot dot dot that has become so common in so many aspects of American life: serving fellow citizens in the halls of the Capitol is a noble pursuit ... if you can afford it.”

Salary set in 1975

The proposal has reignited an old debate about the merits of a pay increase and raised new questions about who would even have the authority to change it.

Legislative salaries are ultimately decided by voters, but the last time aconstitutional amendment was put forth was 1975, more than a decade before the Ethics Commission was created. At the time, legislators made the recommendation themselves. That authority has since legally shifted to the commission.

“I’m pretty sure this has never happened,” Commissioner Steven Wolens said at the September meeting, referring to a salary proposal coming directly before the board. “So the way I see it is that you don’t even go to the Legislature. We would make a recommendation and somehow it shows up on a ballot.”

“That would be certainly something that I would be very interested in studying and considering,” Commissioner Pat Mizell said. “I don’t think we should do it today, but Ms. Caballero, it may be that you’ve set the impetus to get something done.”

Caballero, a lifelong Texan who performs quality assurance for a hazardous waste company near Corpus Christi, started researching the issue this spring after learning that Amazon founder and chief executive Jeff Bezos is on track to become the first trillionaire. Amazon had also just announced it was ending a temporary wage increase for workers during the pandemic. It felt like a ridiculous imbalance.

“I just had this brief, dystopian future glimpse,” she said. “I didn’t feel like the government was doing their part. And I couldn’t bear the idea of standing on the sidelines and shaking my fist for the entirety of my children’s education or their lives.”

Caballero considered running for a seat in the Texas House but quickly realized it was impractical. She has a partner now but has raised her children largely on her own and said she can’t afford to quit working or take months off from work.

“I feel like I would make a great legislator, and that tells me people like me are not able to become legislators,” she said. “And those are the people who want to do good for other people and not just work their way up the power ladder.”

Her proposal, though, put the Ethics Commission in a tough spot. While they have the legal authority to do so, raising legislative salaries could begin to fundamentally change the nature of the job. Serving in the Texas Legislature was never designed to be a singular commitment, in part because of the distance it took many to travel to Austin in the late 19th Century.

There have been several attempts to modernize the system since, including pay raises and meeting more frequently. Most of them have been turned down by voters or quietly killed by other legislators.

Lawmakers from both major parties have been especially frustrated by their inability to gavel in this year, amid the pandemic. Republican Gov. Greg Abbott has declined to call them back for a special session.

“With an economy the size of Texas, it’s ridiculous that we meet every other year,” said Rep. Michelle Beckley, D-Carrollton, one of the few small-business owners in the House. “I don’t think we’re doing anybody a favor.”

Though the current ethics commissioners have all been appointed by Republicans, they are meant to be apolitical. Commissioner Richard Schmidt, a retired bankruptcy judge, pointed out at the September meeting that a pay raise would almost certainly be controversial.

“There are a lot of people who are taking the position that maybe legislators shouldn’t be paid anything, that it should be a voluntary role and so maybe it should be lowered,” he said. “I mean, I’m not in favor of any of that, but I’m just saying this is an issue where there are lots of things to consider.”

It also comes at an especially fraught moment for the state, which is struggling to combat surging coronavirus infections and the financial fallout from them. State officials anticipate a massive budget shortfall heading into the next biennium, and lawmakers are likely to cut spending in the next session, which begins in January.

“It would be politically tone deaf to raise legislator pay in the middle of a pandemic, which is stomping the Texas economy,” said Brandon Rottinghaus, a political science professor at the University of Houston. “So I don’t suspect that you’d see lawmakers ask for this. And I think that they would be probably flat out against it.”

Wealthy legislators

Rep. Gary Gates, a real estate mogul and incoming Republican House member, said he and other wealthy lawmakers don’t need additional salary. But he is open to a need-based option and is also in favor of increasing the amount that legislators are separately allotted to hire office employees — currently set at $13,000 a month.

Since elected, Gates has personally put up tens of thousands of dollars to bring on additional hands and pay for private attorneys to help draft legislation. He has hired three former chiefs of staff and said he paid more than $100,000 for one of them alone, which is a little more than $8,000 a month.

“That’s a lot of experience,” Gates said, adding, “If it wasn’t for the fact that I’ve got the resources, there’s no way I could have the staff that I have.”

Nearly all of the ethics commissioners declined to speak on record. As of early November, the commission appeared to still be looking into Caballero’s idea. In a recent statement, though, Chairman Chad Craycraft said they have no plan to revisit the proposal.

“Such a change would represent a fundamental departure from the principles of our 1876 Constitution establishing apart-time legislature, and the appropriate venue for that conversation would be among our democratically elected representatives,” he said.

Caballero isn’t waiting for anyone to step forward. After discussing it more with her family, she has decided to run for office anyway, despite the financial hurdles, and is eyeing the lieutenant governor’s race in 2022.

Her potential challenger, incumbent Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, has already raised more than $15 million to spend on the race, according to campaign disclosures.

“It’s going to be a lot of work,” said Caballero, a Democrat. “I have no misconceptions about that.” jeremy.blackman@chron.com twitter.com/jblackmanchron

“It’s impossible for a public school teacher to serve (in the Legislature), or a firefighter, a nurse, a police officer — really anybody with a normal job.”

Rep. James Talarico, D-Round Rock, a former teacher who now consults part time