W.Pa. women played pivotal role in suffrage movement

100 years after 19th Amendment was ratified, leaders of today say fight isn’t won until Equal Rights Amendment is passed

by DEb ERDLEy

Tennessee tipped the scales to codify women’s suffrage in the U.S. Constitution 100 years ago Tuesday, becoming the 26th state to ratify the 19th Amendment on Aug. 18, 1920. Long before that, however, the battle to give women the right to vote played out in communities large and small.

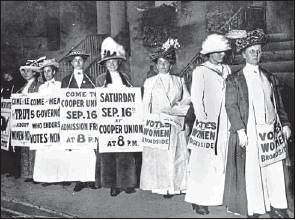

Women from Southwestern Pennsylvania, some of whom would go on to play a significant role on the national stage, were among the leaders of the effort that grew and blossomed in the decade before the ratification of the federal law.

“It took a lot longer than it should have,” Harriet Ellenberger said.

Ellenberger, who has been active for decades, first in the League of Women Voters and the Pennsylvania Federation of Democratic Women, was disappointed when the global pandemic forced the cancellation of the federation’s annual state convention in Greensburg. It was to have been a celebration of a century of women voting. But the Westmoreland County woman decided to celebrate instead that women are increasingly seeking office.

“This year, we have 80 women running for state and federal offices in Pennsylvania — and that’s just the Democrats,” the Norvelt woman said.

They and their Republican counterparts stand on the shoulders of giants.

Women like Hannah Jane Patterson, whose birth and death are recorded on a simple marker in West Newton Cemetery. Elizabeth McShane of Uniontown and Jennie Bradley Roessing and Lucy Kennedy Miller, both of Pittsburgh, aren’t mentioned in high school history texts. But they laid the foundation for a coalition that organized women including factory workers, black church leaders, Sunday school groups and women’s clubs across the state to carry the banner of women’s suffrage through an ill-fated attempt to pass an amendment to the state constitution in 1915 and across the finish line in Washington, D.C.

Some of their work and that of others is detailed in the Pittsburgh’s Suffrage Centennial web page.

Push through Pa.

McShane, a Vassar College graduate who died in 1976 at the age of 84, and Roessing drove areplica of the Liberty Bell (dubbed the Justice Bell) to every county in Pennsylvania in 1915 during the lead up to the vote on the state constitutional amendment. Local newspapers told of how they were met and escorted by local suffragists in every town the bell visited.

The bell, suffragists said, would not ring until women could vote.

Newspapers of the day recorded how the Justice Bell tour hit Pittsburgh over July 4 and continued east with stops documented in Monessen, Scottdale, Greensburg, Derry, Mt. Pleasant, Latrobe and scores of other small towns on the way to Philadelphia.

They nearly won.

James Steeley, a retired high school history teacher who scoured newspaper archives and fading pamphlets to research the local movement, discovered they won in Westmoreland County by 1,000 votes.

In fact, they won across Pennsylvania’s small towns and rural communities.

But the amendment was defeated when voters in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia bowed to intense lobbying by the distilleries and breweries, which believed women voters would side with the Temperance movement and usher in Prohibition, said Leslie Przybylek, a senior curator at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh.

That didn’t stop the suffragists. They soldiered on for another five years as the battle shifted to the national stage.

Although many date the beginning of the movement to the 1848 Seneca Falls (N.Y.) Convention that brought together Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the movement actually dates back even farther and had deep roots among earliest abolitionists, said Colleen Shogan, vice chair of the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission.

As the ebb and flow of the movement gained momentum in the early 1900s, the Southwestern Pennsylvania women were pivotal to its ultimate success.

Their organizational skills were second to none, Steeley said. He credited much of that to Patterson, a banker’s daughter who graduated from Wilson College in Chambers-burg and went on to study finance at Columbia University and finally studied law at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Their organization was unbelievable,” Steeley said.

Shogan, a North Huntingdon native, is senior vice president and director of the David M. Rubenstein Center at the White House Historical Society. A political scientist, she was a senior executive at the Library of Congress before her current appointment.

“It’s incredibly instructive for Americans to understand how perseverance was required to keep the movement going, recruiting new leaders,” Shogan said. “It’s got a lot of lessons in civic leadership. I learn something new every day.”

Local leaders

That Patterson, who served as an assistant to Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of War and returned to Pittsburgh as an investment advisor to a local brokerage, joined Miller and Roessing wasn’t surprising. All three graduated from the Thurston Preparatory School for Girls, now Pittsburgh’s Winchester Thurston School, within a few years of one another.

They took the torch of leadership of the Pennsylvania Women’s Suffrage Association in 1912 and continued working in the movement for women’s suffrage on the national stage after the state effort failed.

In 1917, Patterson and Roessing were elected to leadership posts in the National Woman Suffrage Association. A year earlier, the two women had attended the Republican and Democratic national conventions and persuaded party leaders to include support for women’s suffrage in their platforms.

While they lobbied in the final years leading up to passage of women’s suffrage, McShane joined protests supported by Alice Paul’s National Women’s Party.

She was jailed repeatedly from 1917-19. A biography on file at Vassar includes a searing account from McShane’s diary of how she was force fed when she and other suffragists in jail went on a hunger strike in November 1917.

Shogan said women ultimately prevailed in 1920, in part, because the National Women’s Party and the National Women Suffrage Association took two different approaches.

“I don’t think women would have won the right to vote in 1920 without that,” Shogan said.

Ultimately, the Western Pennsylvania women would be able to celebrate their efforts.

Miller addressed the Pennsylvania General Assembly on June 24, 1919, when its members voted to ratify the 19th Amendment, just 20 days after Congress passed it.

“You have done today the biggest thing you have ever done in your history,” she said.

Equal rights

While they applaud the work their predecessors did, modern activists say the battle for women’s rights continues.

A part of that has been Jeanne Clark, a Harrison native who has been active in the Women’s Movement since her days at Boston University in the 1960s and who founded a local chapter of the National Organization for Women. She ran a women’s health clinic in East Liberty for nine years, worked in the national leadership of NOW in the 1980s, made a failed bid for state Senate in that era and continues that work today in her writing with the Feminist Majority.

Clark said the work women did a century ago is finally coming to fruition as more and more women run for office and win.

Now, Clark would like to see the federal Equal Rights Amendment added to the U.S. Constitution. The amendment that states that “equal rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex” passed Congress in 1972.

Although it failed to be ratified by 38 states within the 10-year time frame set by Congress, states have continued to ratify the ERA. Virginia came on board as the 38th state in January. Legal experts say that’s created a conundrum for Congress and the courts to resolve.

Clark said she intends to keep working for it.

“The women and men who started the suffrage movement didn’t live to see it come about,” she said. “They fought for 72 years. We’ve been fighting almost 100 years for an equal rights amendment.”

The movement didn’t end in Tennessee.

Deb Erdley is aTribune-Review staff writer. You can contact Deb at 724-850-1209, derdley@triblive.com or via Twitter @deberdley_trib.

“It’s incredibly instructive for Americans to understand how perseverance was required to keep the movement going, recruiting new leaders. It’s got a lot of lessons in civic leadership. I learn something new every day.”

COLLEEN SHOGAN

VICE CHAIR OF THE WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE CENTENNIAL COMMISSION