CHRONICLE INVESTIGATION

BAD BEHAVIOR IN COURTS

Justice Department does little to stop immigration judges who regularly make inappropriate remarks, leering ‘jokes’

By Tal Kopan

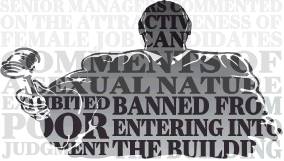

WASHINGTON — One judge made a joke about genitalia during a court proceeding and was later promoted. Another has been banned for more than seven years from the government building where he worked after management found he harassed female staff, but is still deciding cases.

A third, a supervisor based mostly in San Francisco, commented with colleagues about the attractiveness of female job candidates, an internal investigation concluded. He was demoted and transferred to a courtroom in Sacramento.

The three men, all immigration judges still employed by the Justice Department, work for a court system designed to give immigrants a fair chance to stay in the U.S. Every day, they hear some of the most harrowing stories of trauma in the world, many from women who were victims of gender-based violence and who fear that their lives are at risk if they are deported to their native countries.

These judges’ behavior toward women is not an isolated phenomenon in the immigration courts system. A Chronicle investigation revealed numerous similar instances of harassment or misconduct in the courts, and found a system that allows sexually inappropriate behavior to flourish.

In response to detailed questions before President Biden took office, the Justice Department declined to comment on specific allegations against judges, citing the privacy of personnel matters in some instances and the lack of written complaints in others, but said generally that it follows department procedures on misconduct. The Biden White House did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Interviews with dozens of attorneys across the country and current and former government officials, as well as internal documents obtained by The Chronicle, show the problems have festered for years. The Justice Department has long lacked a strong system for reporting and responding to sexual harassment and misconduct.

And when such behavior has come to its attention, the department has in some instances simply transferred the offenders elsewhere.

The judges’ behavior appears to violate the department’s conduct policies and raises questions about the immigration courts’ ability to function fairly. Attorneys who have been the victims of harassment say they fear that if they try to hold judges accountable, they risk severe consequences, not only for themselves but for vulnerable clients.

“In the moment, you just know that you have to stay calm,” said Sophia Genovese, who has been an immigration attorney for three years and worked in the field of immigration policy for five. “You know if you do anything to piss him off, that’s going to ruin your reputation in his eyes. In that moment, am I thinking that I might be perpetuating sexism in the system? No, I’m thinking I just need to get through this.”

She added, “If all you have to do is force a smile so that your client is not deported, the answer is obvious what practitioners are going to do.”

Michelle Mendez of the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, which provides legal representation to immigrants and helps attorneys report allegations of judicial misconduct, said lawyers face tremendous pressure not to call out judges’ bad behavior, even though they know ignoring it means it is likely to continue.

“An immigration judge might retaliate against the advocate by punishing her clients — and these are people fleeing persecution, rape and even death,” Mendez said. “It’s quite literally a Sophie’s choice that should never happen in the American legal system.”

The Trump administration did little to change the pattern, The Chronicle found, and in one case even promoted a judge who many women have said made them feel uncomfortable in open court and behind the scenes for years. Justice Department data shows the administration dismissed more complaints against judges than its predecessor.

It’s a problem that Biden’s administration has inherited. The very structure of the courts creates the conditions that allow bad actors to escape consequences, experts say. But that leaves Biden with a problem, they add: Does he reform the system to be independent of political influence, or does he use his political control over it to clean it up?

* * *

For years, women working at the national headquarters of the immigration courts in Falls Church, Va., shared whispered warnings about Judge Edward R. Grant.

Grant, who has served on the Board of Immigration Appeals since 1998, is one of 23 judges who weigh appeals from immigrants who have lost cases in the nearly 70 immigration courts around the country. He and his colleagues are the next-to-last hope for immigrants. If they lose before the board, their only hope of avoiding deportation is a long-shot case in federal appellate courts.

In the early 2010s, a woman’s complaint about Grant’s behavior caught the attention of then-President Barack Obama’s director of the immigration courts, who opened an investigation. Supervisors concluded that Grant had harassed female staffers, and took an extraordinary step: They banned Grant from the court building.

The department did not take away Grant’s responsibilities or six-figure salary. He was allowed to keep his job, and still has it to this day, though he remains barred from working in the appeals court’s headquarters unless his presence is unavoidable, such as in rare instances when the board hears oral arguments.

Case documents are sent to and from Grant’s home, multiple sources familiar with the situation told The Chronicle. Grant issues his rulings without seeing the inside of a courtroom.

In a Freedom of Information Act response, the Justice Department confirmed that a board member was banned from the building in April 2013 as a result of a complaint against him. The confirmation came in a reply to immigration attorney Matthew Hoppock’s request. Hoppock, who practices in Kansas City, Mo., frequently files requests for information from immigration agencies, which he then makes public.

The Justice Department’s response did not identify the judge. But sources familiar with the situation confirmed it was Grant and that the complaint involved sexual harassment. The sources declined to talk on the record because of the sensitivity of the subject matter.

In the response regarding the board member that The Chronicle identified as Grant, the department’s Freedom of Information Act counsel confirmed that one complaint of misbehavior “resulted in the Board member being banned from entering into the building.” The counsel’s office refused to share the original claim against Grant or the disciplinary letter with Hoppock, citing the individuals’ privacy protections. Hoppock shared the response with The Chronicle.

The Justice Department cited its policy of not commenting on personnel matters in declining to answer questions to The Chronicle about Grant’s banishment. Grant did not respond to requests for comment.

* * *

Supervisors of judges have also engaged in behavior that could give rise to harassment or misconduct claims, according to a 2019 Justice Department inspector general’s report obtained by The Chronicle.

One former top supervisor who oversaw immigration judges in the court system made sexual jokes and talked with colleagues about whether female judge candidates were attractive, the report found. Other senior managers also commented on the women’s appearance, it said.

A redacted copy of the report was provided to The Chronicle by Hoppock, who also received the inspector general investigation through the Freedom of Information Act. Although the supervisor’s name was blacked out, multiple sources familiar with the contents of the report confirmed it was Print Maggard. They requested anonymity because of the sensitivity of the subject matter.

Maggard was a supervisor from 2012 to 2019, mostly based in San Francisco, and for a year during the Obama administration was acting chief of all immigration judges, working in the headquarters building in Falls Church. He also served as an immigration judge from 2009 to 2011 in San Francisco, and he was an Immigration and Customs Enforcement attorney in the city from 2006 to 2009.

The investigation of sexually inappropriate behavior is tucked away in the inspector general’s report, which is mainly about personnel misconduct, and was left out of a public summary. But investigators wrote in the full report that they substantiated such allegations against Maggard and other supervisors.

“We concluded that (redacted) made comments of a sexual nature and commented on the attractiveness of female candidates with court employees with whom he socialized and trusted, and that they willingly participated with him in making such comments themselves,” investigators wrote. He wasn’t alone, they added: “We concluded that he participated in conversations in which other senior managers commented on the attractiveness of female job candidates.”

The actions did not constitute sexual harassment under Justice Department policy, the report said, because the subjects of the comments were unaware of them and the policy “requires that the conduct be unwelcome.” Maggard was joking with willing colleagues, the report said.

Instead, the report concluded that Maggard “exhibited poor judgment” and “should have avoided” such behavior. His comments “could give rise to claims of sexual harassment or claims of prohibited personnel practices,” it said.

Maggard did commit clear personnel misconduct, the investigators concluded. He improperly provided sample questions to a job candidate in advance of the person’s interview and escorted a friend to another interview, an impermissible boost to her job application, investigators said.

After the report was completed in November 2019, Maggard was demoted and reassigned to be an immigration judge in Sacramento. He is still there, hearing immigrants’ cases but stripped of his supervisor duties.

The Justice Department cited its policy of not commenting on personnel matters in refusing to answer questions about Maggard’s conduct. It declined to say whether the others who participated in the conversations with Maggard were identified or faced consequences. Maggard did not respond to requests for comment.

***

The Chronicle found examples across the country of judges who have made sexual jokes or who habitually made attorneys or staff uncomfortable in the courtroom. Such behavior often goes unchecked because there is no regular oversight of judges’ demeanor by Justice Department leadership, and attorneys say the formal complaint process is inadequate.

In the Atlanta immigration courthouse, attorneys were dismayed when the Trump administration promoted Judge William Cassidy in 2019 to serve on the Board of Immigration Appeals.

Nearly a dozen attorneys who have argued cases before him since the 1990s told The Chronicle that his behavior was frequently inappropriate.

“You know if you do anything to piss him off, that’s going to ruin your reputation in his eyes. In that moment, am I thinking that I might be perpetuating sexism in the system? No, I’m thinking, I just need to get through this.”

Sophia Genovese, immigration attorney

In one instance, captured on courtroom audio, Cassidy had just granted relief from deportation in 2019 to a green card holder from Germany. She had lived in the U.S. most of her life and began using marijuana after suffering multiple miscarriages, leading to criminal convictions that made her subject to deportation.

To have her deportation canceled, she had to convince Cassidy she was deserving and had a reason to stay in the U.S. That reason, she testified, was her school-age daughter, who was born prematurely and had special needs.

The judge ruled in her favor. As the woman sniffled audibly, Cassidy told her he had bonded with her over the story, as he also was born prematurely.

Cassidy said he weighed just 3 pounds at birth. The woman asked how long he was.

“How long was I? Oh, men never answer that question,” Cassidy said. The woman did not acknowledge the joke, though someone else in the court laughed.

The recording was provided to The Chronicle by the woman’s attorney, Genovese, who was practicing in Atlanta with the Southern Poverty Law Center. She said she recoiled at the joke, but didn’t find it out of the ordinary for Cassidy. She said it wasn’t until she told the story to colleagues who worked in other federal courts, and saw them react with horror, that she realized it was uncommon behavior for a judge.

“At the time, it was annoying but typical Cassidy,” Genovese said. “It really took them ... pointing out how serious this behavior was for me to realize that this is not ordinary behavior for other (federal) judges. And yes, objectively, I know it’s a sexist comment, and also it’s just so commonplace with immigration judges to make inappropriate comments like this and there’s just no accountability for it.”

In another instance, an attorney told The Chronicle she was reviewing a case file in the court offices when Cassidy walked up and began chatting with her. He cracked a joke, and she was not amused, which Cassidy noticed.

“He basically said to me, ‘Are you naturally a blonde maybe?’ Like, I don’t get it because I’m a blonde, not a brunette,” said the attorney, who requested anonymity because she still practices before the Atlanta court and is concerned about the way sexual harassment victims are treated when they go public.

As Cassidy stood over her, the woman said, the judge added, “Are you basically telling me that the carpet doesn’t match the drapes?”

That lewd expression refers to a woman’s pubic area.

The Chronicle spoke with three people who confirmed the attorney shared the story with them shortly after it happened.

“Even when I’m saying it now, I feel like I’m starting to get red in the face,” the attorney said. “I remember feeling very, very embarrassed and shaking, and I went completely red. All I remember is him just laughing like he had made a funny comment that we should all think is funny.”

Genovese and other attorneys in Atlanta say such behavior was routine for Cassidy. None complained in writing to the Justice Department, saying they feared it would result only in the judge being angry at them and taking that anger out on their clients.

Complaints about immigration judges are not made public. But limited available records show that at least 11 complaints have been filed about Cassidy with the Justice Department regarding his in-court conduct toward attorneys, immigrants and even another judge. None of those deals with sexist or sexually inappropriate behavior, instead focusing on improper handling of the judicial process.

These records, covering 2008 to 2013, were made public by attorney Bryan Johnson and a coalition of immigration legal groups after they received them through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit.

Another complaint alleging violations of immigrants’ rights by Cassidy and other Atlanta judges was filed in 2018 and made public by the Southern Poverty Law Center, which advocates for immigrants and civil rights.

Together, the documents show mild consequences for subjects of repeated complaints, including Cassidy. Six of the 11 complaints resulted in no consequences, either because managers couldn’t substantiate the allegations after reviewing the record or the issues raised were matters to be decided in the appeals process. Five led to counseling by Cassidy’s bosses on how he should conduct himself.

Many attorneys who have practiced before Cassidy say they decided they were better off brushing aside his conduct toward women than filing complaints.

“What happens with this behavior is that it is so cumulative that it becomes like background noise,” said Carolina Antonini, who practiced before Cassidy from the 1990s until his promotion. “It is an ever-present buzz. And if someone says, ‘No, no, you have to identify it,’ and you cannot, they say, ‘Well, it doesn’t exist.’ ”

Hiba Ghalib, an attorney who practices in Atlanta, said of Cassidy’s behavior: “There was never anything so direct that it was anything I could file a complaint on — it was just uncomfortable and annoying. But at the end of the day, I know how far a complaint could take me. ... It never really got me anywhere, and it created enemies.”

Attorneys say Cassidy’s behavior should not have been a secret to the Justice Department. The director of the courts in the department, James McHenry, spent 2005 to 2010 and 2011 to 2014 in Atlanta as an attorney for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement office that prosecutes immigration court cases. In those roles, he appeared in numerous cases before Cassidy.

A Freedom of Information Act request made public by Johnson revealed they grew close enough that they corresponded personally years later, with Cassidy wishing McHenry a happy Christmas and Easter in emails in 2018 and 2019, the year former Attorney General William Barr named Cassidy to the Board of Immigration Appeals. As director, McHenry oversees the hiring process for the board.

Antonini, who also knows McHenry, said he should have been well aware of Cassidy’s in-court behavior.

“If the current person in charge didn’t know him, I would get it,” Antonini said of Cassidy’s promotion. But, she said, “he was in front of him.”

The Justice Department and McHenry declined to comment on McHenry’s relationship to Cassidy or his role in promoting him. The department said all hiring for immigration courts and the Board of Immigration Appeals follows an open, merit-based process. It said the earlier complaints against Cassidy did not include allegations of harassment and showed “no evidence he has engaged in serial misconduct.”

The department said it could not comment on the incidents raised to The Chronicle because the attorneys involved did not file complaints.

“Cassidy is frequently a target of ad hominem attacks, threats, and unsubstantiated accusations by commenters and advocacy organizations who simply disagree with the merits of his decisions,” spokesperson Kathryn Mattingly said in a statement. The department “does not tolerate complaints whose sole purpose is to harass, threaten, intimidate, or retaliate against its adjudicators based on their rulings.”

Cassidy did not respond to requests for comment.

* * *

The Chronicle’s investigation revealed that inappropriate behavior by judges was far from uncommon in immigration courts around the country, and that the comments made by the Atlanta attorneys echoed sentiments voiced by their peers nationwide.

Attorneys Ivan Yacub and Lauren Truslow represented a woman seeking asylum in Arlington, Va., arguing she was a victim of sex trafficking and had been brutally sexually assaulted in her native country.

Immediately before a May 2019 hearing in which the woman would testify in detail about her trauma, the attorneys said, Judge Paul McCloskey gave instructions on how the hearing should proceed.

He said, “Good testimony should be like a skirt — should be long enough to cover everything but short enough to keep it interesting,” both attorneys recalled in an interview. The comments occurred before the judge opened the recorded portion of the hearing, they said.

Truslow, who said it was her first hearing on the job, was furious.

“I just remember feeling kind of enraged that I was wanted (by him) to laugh,” she said. “For this man to have such disregard for women ... particularly in a professional environment, being reminded that we are first and foremost a sex object for some people.”

She said the comments ate away at her for months before she sent an email notifying other attorneys who practice in the area.

“I don’t want my daughter to grow up to become a professional and still have to suffer that kind of thing in this environment,” Truslow said.

The Justice Department said that without a written complaint, it could not comment on the allegation. McCloskey did not respond to requests for comment.

Other attorneys recalled judges who minimized domestic violence while questioning asylum seekers, or suggested that married women could not be raped by their husbands. The Southern Poverty Law Center and another nonprofit group, the Innovation Law Lab, compiled several examples from focus groups of attorneys they held, which were included in a report criticizing the immigration court system. The attorneys were not identified by name in the report.

In a sworn affidavit in an administrative complaint filed with the Justice Department, one attorney wrote that a judge in El Paso, Texas, commented on the attractiveness of an asylum seeker as if it were an explanation for her persecution.

A complaint about a San Francisco judge alleged he used incorrect pronouns for a transgender immigrant and asked one who was testifying about being tortured by police whether “anyone ever insert(ed) anything into your ass in custody.”

* * *

Removing judges who commit misconduct from the courts will be no easy task for Biden, as the system itself is part of the problem, experts say.

The immigration courts are housed within the Justice Department, meaning the judges are hired directly by the attorney general, a political appointee with a policy agenda. The attorney general alone holds the power to fire immigration judges.

Sexual harassment has been a recurring problem in the Justice Department itself. A 2017 inspector general’s report that detailed the department’s mishandling of sexual harassment in the civil division, a separate division of the agency, prompted a new set of agencywide policies and definitions on harassment and misconduct. Much of the behavior that was described to The Chronicle appears to fall under those definitions.

A 2018 memo by then-Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein in response to that report defines sexual harassment as conduct including unwelcome advances or other behavior that creates an “intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment.” That includes “telling sexually oriented jokes” and “making sexually offensive remarks.”

The memo said the term “sexual misconduct” includes on- and off-duty behavior. It said substantiated allegations will “be treated seriously and ... consistently result in formal discipline up to dismissal.”

“What happens with this behavior is that it is so cumulative that it becomes like background noise. It is an ever-present buzz. And if someone says, ‘No, no, you have to identify it,’ and you cannot, they say, ‘Well, it doesn’t exist.’ ”

Carolina Antonini, immigration attorney

But The Chronicle’s reporting showed little sign of improvement in practice.

Denise Slavin, who served as an immigration judge from 1995 to 2019, is president emerita of the union that represents immigration judges and still advises the organization. In an interview, Slavin said the Justice Department’s immigration courts division has long had a problem with discipline because it doesn’t make policing judges’ conduct a priority, and because of a workplace culture that has at times been unfriendly toward women.

“My assistant chief immigration judge once told me, ‘You would have to murder someone, with an ax, with your robe on and nothing on underneath, in court to get disciplined,’ ” Slavin said. “There was just no real concern about conduct by management at that point, and in addition to that, there was no real way that they got feedback about it, because there were no assistant chief judges in the field.”

She said the situation improved in recent years as more supervising judges were placed in the regions they oversee. But she said the Trump administration focused on different priorities — namely, speeding up deportation cases and limiting immigrants’ ability to win asylum.

She said the Trump administration further chilled those who would complain about judges’ behavior with its choices of which judges to promote.

“With this administration, the attitude is, if you do something horrible in terms of misconduct, you’re going to get promoted to the Board of Immigration Appeals because of the people they put up there,” Slavin said of the Trump era. “Some of the appointments they have made up there have been some of the worst offenders.”

***

The immigration courts do have a system for reporting complaints. They go to the judges’ managers, assistant chief immigration judges, a position Maggard held in San Francisco.

It is not a system designed to protect complainants. If the allegations are specific, it takes little effort for a judge to figure out who filed the complaint, and attorneys describe instances of judges retaliating without consequences.

Some complaints are never shared in detail with the judge, and those who file them are not told the outcome. The complaints are not made public.

However, the documents from 2008 to 2013 revealed through the Freedom of Information Act request show a process in which many complaints are given only cursory investigation by the supervising managers, and in which consequences are usually limited to verbal counseling.

An analysis of those records by Mendez’s group, the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, showed only a handful of instances in which judges were suspended. Among the infractions that brought only counseling: a judge who said of an immigrant, “She has no value or has demonstrated no value or service to the community but for a sexual service.”

Another judge was only reprimanded for what a Justice Department document described as “inappropriate comments regarding rape victims and premarital sex.”

Under the Trump administration, the number of complaints dismissed jumped from roughly 40% in 2015 and 2016 to 60% in 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020. Data for the latter two years was posted online after The Chronicle inquired why reporting had stopped after 2018.

No complaints resulted in formal discipline in 2017, 2018 or 2020, and 5% or fewer did other years. The bulk of complaints that were sustained were met with “corrective actions,” including training or counseling. Other judges may have been fired, but the department does not separate firings from retirements or resignations in its data.

The department said all of its employees complete mandatory sexual harassment and misconduct awareness training. It did not say whether it offers any additional gender sensitivity training for its judges.

The Chronicle reported in October that the Trump administration canceled all diversity training, including for immigration judges. Mattingly, the Justice Department spokesperson, said the immigration courts agency requires judges it hires to have demonstrated “appropriate temperament” and follows department policies on sexual misconduct.

She said the agency takes allegations of misconduct seriously and that anyone with a valid complaint should file it. She added that the court system “explicitly forbids retaliation.”

But in practice, there is little to prevent judges from retaliating against someone who complains, attorneys say. Attorneys go before the same judges regularly, and those judges’ wide discretion gives them ample room to make life difficult for a lawyer who crosses them.

In comparison, for its state court system, California has a Commission on Judicial Performance to investigate complaints against judges, an independent agency with investigatory powers and authority to impose discipline.

“A complaint process that’s not transparent loses about 90% of its utility,” Slavin said. “You can have a judge that has three or four complaints against them, and action is being taken, but if no one knows, the judge can hide it and no one knows the complaints are doing anything. ... The complaint process doesn’t effectively serve management, doesn’t effectively serve the judges or employees of (the agency), and it certainly doesn’t effectively serve the public.”

The National Association of Immigration Judges said it supports an overhaul of the department’s complaint process. It called the current system difficult to use for complainants and judges alike.

“Sexual harassment cannot be tolerated or condoned in our nation’s immigration courts,” said the group’s executive vice president and president emeritus, Judge Dana Leigh Marks, who works in the San Francisco immigration court. “It is unacceptable for anyone with a track record of inappropriate behavior to be protected and promoted. Because the immigration courts are part of a law enforcement agency, politics too often plays a role in the promotion and retention practices in the immigration court system.”

McHenry, the Justice Department courts director, issued a memo in August 2019 on “allegations of misconduct,” saying judges are expected “to adhere to the highest standards of ethical conduct and professionalism and to maintain impartiality.”

He also warned attorneys not to make baseless complaints designed “to harass, threaten, intimidate, or retaliate against” judges.

The agency “expects parties and stakeholders to raise legitimate concerns about conduct, rather than simply make ad hominem attacks against adjudicators or express disagreement with the outcome of a particular case,” McHenry wrote.

* * *

Democrats and many of the groups that represent immigration attorneys and judges have argued that the courts should be removed from the Justice Department and reimagined as a standalone court system, resembling systems like the bankruptcy courts. Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-San Jose, who chairs the House subcommittee on immigration policy, has been working on a bill to spin off the courts, but has yet to introduce it.

“Creating an independent immigration court seems to me like a no-brainer,” Lofgren said at a hearing in January 2020. “The time to act is really now. It’s my hope that this hearing will be a first step toward negotiating a bipartisan, workable solution to what is really a crisis in our immigration courts.”

In her statement, Marks of the National Association of Immigration Judges called an independent court system “the only sustainable solution” to check “against the politics that has plagued the immigration courts over the years.”

But making the courts independent would keep the Biden administration from directly changing the system, including firing bad-actor judges. Biden has proposed legislation that would expand training for judges and give them more discretion to grant protections to immigrants.

Slavin said Biden’s first priority should be hiring new judges to deal with a backlog of cases and to counterbalance Trump’s hundreds of hires who she said favor deportation, and that he should rescind many of the Trump administration’s immigration policy changes.

Only then, she argues, should he support legislation making the courts independent.

“The bottom line is, if you don’t do that by the end of your administration, the next administration is going to come in and do the same (undoing) to you,” Slavin said.

Without an independent court, said Mendez, the Catholic Legal Immigration Network advocate, there will never be accountability.

“As long as immigration courts remain under the executive branch,” she said, “given how politicized immigration is as an issue, we will continue to have foxes guarding the henhouse.”

Tal Kopan is The San Francisco Chronicle’s Washington correspondent. Email: tal.kopan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @talkopan

“There was never anything so direct that it was anything I could file a complaint on — it was just uncomfortable and annoying. But at the end of the day, I know how far a complaint could take me. ... It never really got me anywhere, and it created enemies.”

Hiba Ghalib, immigration attorney

ONLINE EXTRA

Read the story online to hear one of the exchanges between a judge and attorney: