Unique set of hurdles for older HIV patients

By Erin Allday

Older people with HIV are frequently lonely and depressed, many of them face serious housing and financial hardships, and they have high rates of physical ailments — such as chronic pain, heart disease, diabetes and fatigue — that can diminish their quality of life.

All of that’s been known for several years. But services to meet their needs still fall short, say people with HIV and the groups that support them, and simply quantifying their mental and physical health problems has been a challenge.

People age 50 and older make up nearly two-thirds of all those with HIV in San Francisco. Most of these older adults have been infected with the virus for 20 or more years. They are the long-term survivors: men and women who were infected before drugs to treat HIV were widely available, when the illness was considered a death sentence.

Though those drugs were life-saving, for many survivors, realizing they were going to live opened a new chapter of emotional and physical challenges.

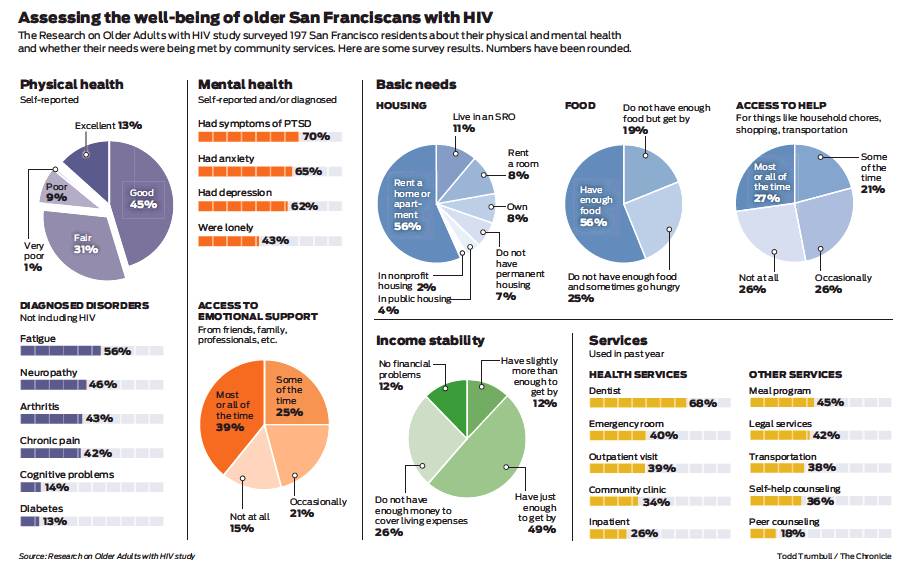

A new survey, released Saturday, is among the first to describe the breadth of health problems in San Francisco’s older adults with HIV and how they are, or are not, being addressed. The survey questioned 197 people, all age 50 or older and HIV-positive. Among the findings:

“There are things worse than AIDS, like loneliness.”

Respondent to survey of HIV survivors age 50 and older

More than 60 percent suffer depression and about the same have serious anxiety. Seventy percent have symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Nearly half have neuropathy, a form of nerve pain likely caused by HIV or the early drugs to treat it. Fifty-six percent have severe fatigue. On average, survey respondents reported at least six mental or physical ailments in addition to HIV infection.

A quarter regularly don’t have enough money to cover their expenses. Seven percent don’t have a permanent home. Nearly half say they sometimes don’t have enough to eat.

More than 1 in 4 said they have no one to turn to if they become sick or disabled and need help with simple chores, like housework or shopping.

Fifteen percent say they have no one to count on for emotional support.

“When you have a population that didn’t plan to live, it’s not surprising that they would find aging challenging,” said Vince Crisostomo, who runs the 50-Plus Network, a group for older men with HIV at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. “There are some days when people see what a blessing it is to be alive. And then there are the harder days.”

Or in the words of one survey respondent: “There are things worse than AIDS, like loneliness.”

Roughly 6,000 long-term survivors live in San Francisco. Along with older people who were more recently infected, they make up the bulk of the modern San Francisco HIV epidemic, but the virus is still perceived by many — from doctors and nonprofit leaders to public health and infectious disease experts — as afflicting primarily the young. Programs that draw the most resources and attention tend to focus on prevention and early treatment.

Meanwhile, though the needs of older people with HIV are becoming much more widely known, services for them have not kept up, according to people with HIV and many of the service providers themselves.

Specialty programs do exist. Crisostomo’s group has more than doubled in size over the past five years, and he now sees 60 to 70 people at his Wednesday night meetings. Early last year, Ward 86 — the HIV department at San Francisco General Hospital —opened a geriatric clinic for older patients.

Nonprofit groups that were founded during the worst years of the epidemic have introduced services from “buddy systems” for older adults to special nutrition programs for people with conditions such as heart disease associated with aging.

Certainly some older adults with HIV say they are impressed by the services available to them. “It’s just heaven for me here,” said Vic McManus, 56, who moved to San Francisco from Long Beach a year and a half ago and soon after joined Crisostomo’s 50-Plus group.

“There’s just so many more resources here,” McManus said. “I feel like I can flourish here, whereas where I came from, I couldn’t even find a support group.”

Still, even those working with agencies meant to help people with HIV worry that they’re not doing enough to help older clients. The San Francisco Model of care — a grassroots network that built up around AIDS in the 1980s and ’90s — hasn’t kept up with the population it was founded for, said Mark Ryle, chief executive of Project Open Hand, which has been providing free meals and groceries to people with HIV for more than three decades.

More than 90 percent of the group’s HIV clients are older than 50 now, Ryle said. Though his agency has taken steps to meet their needs and he knows that other nonprofits have done the same, he also feels as though the long-term survivor community has been let down.

“These long-term survivors, these folks who made it through the gantlet, we thought we had them on autopilot. We thought they had all these services, they’re OK,” Ryle said. “I think to some extent we took the eye off the ball.”

The new survey, called Research on Older Adults with HIV 2.0 — it was a follow-up to a similar survey done in New York in 2005 — was conducted this year by the Acria Center on HIV and Aging at Gay Men’s Health Crisis, an HIV group based in New York.

Participants were recruited largely through service organizations in San Francisco and were asked to fill out 70-page surveys. Acria is conducting similar surveys in Oakland and several other U.S. cities and hopes to eventually include 3,000 older adults with HIV.

The San Francisco survey results weren’t surprising to older people with HIV or to the people who work with them. But they are an important step in drawing attention to the issues around HIV and aging, especially for people outside the epidemic who may not know how the demographics and needs have shifted, said researchers who put together the survey.

“The older adult population dominates the epidemic. A lot of people still don’t know that,” said Stephen Karpiak, senior director for research at Acria and a co-author of the survey report. “We’ve done a very good job to this point (in the epidemic), but we’re not prepared to do the next leg, which is a difficult one. And the older adult is feeling abandoned.”

Jesus Guillen, who was diagnosed with HIV in 1986 and is founder of a Facebook group for long-term survivors, said that if anything, the survey underestimates the issues affecting his community.

He believes that loneliness, which was reported by about 40 percent of survey respondents, is far more prevalent. Social isolation is widespread, he said, and those who are most isolated aren’t easily reachable for surveys and other kinds of studies.

In his Facebook group, members often talk about depression and suicide, about extreme fatigue and chronic pain. They frequently worry about finances and about losing their housing, especially in an expensive city like San Francisco.

Guillen himself has suffered multiple physical and mental health setbacks that he connects to being a long-term survivor. He’s had neuropathy for decades. Two months ago he had a hip replacement, which he needed because of early onset osteoporosis. Last year, he had a mild case of Kaposi’s sarcoma, the skin cancer that was once a hallmark of AIDS. He’s suffered bouts of depression that kept him holed up in his Hayes Valley apartment for days.

“I don’t think this study really illustrates how difficult it is,” said Guillen, 58. “It really feels that if we are not doing something for this community soon, we will have more people dying.”

Some of the ailments described in the report are directly tied to HIV infection. People who have been HIV-positive for several decades may be disabled by pain or mobility issues caused by the infection or the drugs to treat it.

But other conditions are less obviously tied to HIV. People sometimes suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder from the extreme grief they suffered from losing so many friends and lovers to AIDS, or from fearing for their own life for so many years. Problems such as depression and loneliness also may be caused by the loss of so much of their community.

Physical conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and arthritis may be linked to HIV, but doctors still aren’t clear on that. For many years, scientists believed that HIV caused premature aging, but studies have since shown that may not be the case. Older people with HIV aren’t necessarily suffering these conditions earlier — they’re just contracting more of them than would be expected for someone their age.

Complicating their care is that most older adults with HIV are used to seeing an infectious disease specialist for treatment — someone with expertise in HIV in particular. But those doctors don’t necessarily know how to treat heart disease or arthritis or diabetes, or all three at once.

San Francisco General’s geriatric clinic, called Golden Compass, is meant to bridge that gap in care, said Dr. Monica Gandhi, medical director of Ward 86. But it’s just one clinic and can’t be expected to handle the thousands of older adults with HIV in San Francisco.

Though Golden Compass is designed to help patients beyond their physical ailments — addressing isolation, stress, addiction and other concerns — doctors and nurses there can do only so much to help with anxiety around housing and finances.

In Crisostomo’s 50-Plus group, participants often talk about the stresses of just getting by in a city they can’t quite afford but also can’t afford to leave. Few other places have the doctors and other resources that San Francisco provides, even if it’s still not enough, said Kim Armbruster, 65.

“I feel like I can’t leave because of the HIV care in San Francisco. At the same time, I feel like I can’t stay because everything has gotten so outrageously expensive. It’s kind of pressure from both sides,” Armbruster said.

“Being HIV-positive and being in San Francisco — I won’t say it’s a marriage made in heaven,” he said. “But I’m glad I’m in San Francisco and not Tucson or Napoleon, Ohio, where I grew up.”

Erin Allday is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: eallday@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @erinallday

LAST MEN STANDING

Read reporter Erin Allday’s in-depth profile of eight survivors of the AIDS epidemic: https://projects.sfchronicle.com/2016/living-with-aids