JOHN KING Urban Design

$1.4 trillion plan for a better Bay Area

Officials vote for utopian vision — with wariness about its success

The thing about long-range plans for cities or regions is that they map out a civic utopia — but rarely include the tools to reach that promised land in real life.

So even as Bay Area elected officials voted unanimously last week to approve what in many ways is the most ambitious such plan in the region’s history, they emphasized that work will begin in 2022 on pursuing the distant goals — and acknowledged that similar grand plans in the past have left little mark.

“Plans don’t build (housing) units,” said Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguin, president of the Association of Bay Area Governments. “What counts are the actions we’re going to take.”

Arreguin’s comment came moments before the passing of Plan Bay Area 2050, which maps out 35 strategies to improve the region while, in the words of the plan, “confronting huge societal forces in a way that is both equitable and pragmatic.” The vote last Thursday was by appointees to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the executive board of the Association of Bay Area Governments.

If all goes according to plan, good times are ahead.

Highway bottlenecks would be uncorked. A new BART tunnel would cross the bay, while improved bus service and bicycle lanes would make it easier to stay out of cars. Sea level rise would be tackled on a regional basis, with funding for shoreline improvements in lower-income communities that are particularly vulnerable.

Programs ranging from regional rent control to increased affordable housing construction would help ensure there are convenient places for low-income households to live. There’d also be $30 billion for new parks and trails.

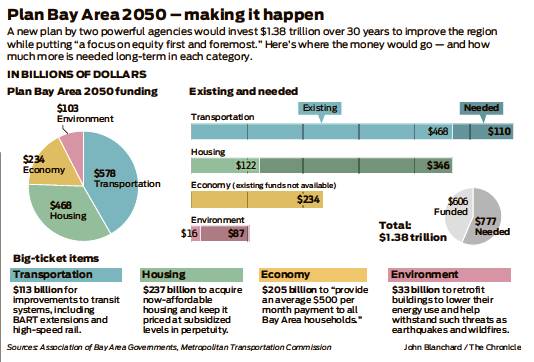

Idyllic as all this might sound, the big question is where the money would come from to make such dreams reality. The price tag to implement the 35 strategies in Plan Bay Area 2050 is $1.4 trillion. Current revenue sources would generate less than half that — most of it in transportation funding.

That’s why the 2022 agenda that was laid out before the vote emphasizes the need to push for funding sources and legislative changes that would generate long-term revenue streams. One example: Regional officials hope to add some form of tolls or fees for using major roadways, but any such effort would require federal and state restrictions to be loosened.

“The implementation of this plan is going to require a tremendous amount of advocacy ... in Sacramento and Washington for the resources that we’ll need,” Amy Worth, mayor of Orinda and a member of the transportation commission, said shortly before voting to support “this incredible effort.”

There’s also the need to build confidence among skeptics by beginning to show results.

For instance, a recent $20 million state housing grant will be used in part to expand an existing San Francisco program that helps families seeking affordable housing. It allows them to apply only once, rather than with every government agency or nonprofit developer that provides such housing.

“That’s a very burdensome process” for families that already might be struggling, said Dave Vautin, an assistant planning director for the commission and association. “Our vision is to expand something like that (the San Francisco program) to all nine Bay Area counties.”

Another set of funds would be aimed at grants to cities — often smaller ones with relatively few funding sources — to plan for ways to preserve or attract blue-collar jobs that would reduce the need for their residents to embark on long commutes.

The most visible near-term impact likely would involve the transportation sector, planners say, since $1.1 billion is heading to the region in new state and federal funding to be allocated between 2022 and 2026. The idea is that grant applications from cities and counties will be judged by how — or if — the local programs are in sync with the larger goals of Plan Bay Area 2050.

Despite the unanimous vote, there were hints of the tensions that likely await in a nine-county region filled with cities that often differ in their take on what appropriate growth should look like.

On one end of the spectrum at the hearing was Millbrae City Council Member Gina Papan, who in the past has argued that pushing for dense development at suburban transit hubs can backfire environmentally — at least if it takes away so much parking that commuters decide it’s easier to stay in their cars than hop onto BART or other systems.

“This plan has amazingly lofty objectives,” Papan suggested. “Some of them have built-in conflicts.”

San Francisco Supervisor Hillary Ronen is wary of how the plan says her city should provide 213,000 additional housing units by 2050. This would be achieved in part by rezoning transit-friendly neighborhoods such as the Mission, which she represents.

“I fear tremendously that the amount of housing that San Francisco is expected to produce, without any commitment to financing for affordable units, could lead to further displacement and gentrification,” Ronen said.

That concern was echoed by the Yerba Buena Neighborhood Consortium, a San Francisco housing advocacy group. The consortium said in a letter that unless full funding for the protection and construction of apartments for lower-income people were nailed down in advance, the plan would amount to nothing more than “an empty shell full of broken promises.”

Regional planners understand the skepticism. They also counsel patience.

“The plan is aspirational, and change takes time,” said Matt Maloney, director of planning for the transportation commission. “These things don’t all get implemented in one or two years. They take 10 or 20 years.”

John King is The San Francisco Chronicle’s urban design critic. Email: jking@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @johnkingsfchron