Renters struggle to tap relief funds

Tenants desperate, but accessing money is tortuous

By Lauren Hepler

Victoria Medina has always loved to cook. But lately, there’s a lot more urgency when she steams her chile verde tamales.

After losing her job as a contract kitchen worker at Google last spring, the 47-year-old mother of three started selling her tamales for $3 each near the Mission District apartment where her family has lived since 2004. But Medina is still $9,000 behind on rent and owes another $2,500 for utilities. Two applications for rent relief have yet to pan out. So she prays in the bedroom she shares with her youngest daughter, her two older children splitting bunk beds in the living room.

“Más que nada ahorita estoy buscando la ayuda,” Medina said.

“More than anything right now I’m looking for help.”

From San Francisco to San Jose to outlying Solano County, some 148,000 households in the ninecounty Bay Area are behind on rent, according to an estimate by the National Equity Atlas. For lowerincome renters like Medina, Gov. Gavin Newsom has vowed to use $5.2 billion in emergency funding to pay 100% of pandemic rent debt from April 2020 to September 2021.

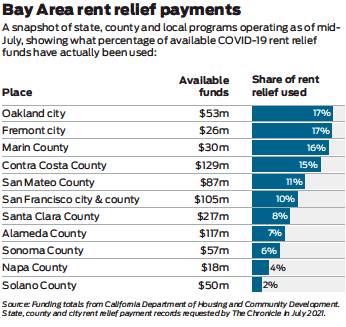

But public records obtained by The Chronicle show that seven months after the federal government first announced the unprecedented aid effort, state and local rent relief programs in the Bay Area have paid out just $88.5 million as of mid-July. That’s about 10% of the $889 million the U.S. Treasury allocated to the region.

Though housing experts say the programs are crucial to keep people housed, interviews with two dozen tenants, landlords, public officials and advocates reveal that the historic expansion of the housing safety net has given way to frustration and confusion about a maze of state and local programs distributing the money.

In a state where housing prices have long risen faster than wages — forcing tenants into crammed apartments, garages, RVs and other unstable situations — they say rent relief is about more than paying down debt before another eviction moratorium expires Sept. 30. It’s an attempt to hold together a housing market that increasingly resembles a house of cards.

“There’s a huge amount of money that’s flowing,” said Beth Daviess, a staff attorney at Legal Services of Northern California. “That money just hasn’t gotten to where it’s supposed to go.”

Officials stress that payments are accelerating after state lawmakers moved in June to make it easier for tenants to directly apply for 100% relief, instead of a previous version of the program where landlords had to forgive some debt. But attorneys like Daviess report that eviction cases are already piling up, and some renters are still struggling after massive unemployment delays or taking out loans to pay for housing.

What’s causing rent relief delays varies from place to place, since different public agencies and contractors run the programs. San Francisco hadn’t paid out a single dollar in local rent relief funds as of July 12, a spokesperson told The Chronicle, even as a separate state program in the city paid out $10 million. In Solano County, the opposite was true; the county had paid around $1 million to cover rent debt by mid-July, but the state program had paid $0. Oakland’s city program temporarily stopped taking applications after overwhelming demand. Some counties report the amount “awarded” or “approved,” but it’s unclear how much has actually been paid.

Among the common challenges are sorting out which program will pay for what, how to get through to hard-to-reach renters and preventing fraud while publicizing a huge amount of cash available. Lawmakers emphasize that tenants who pay 25% of back rent or have a pending rent relief application will be allowed to stay past the Sept. 31 eviction moratorium — if they take steps to document hardship, have proof of their application and can withstand any legal threats.

Amid an uneven economic recovery and resurgent virus, the pressure is once again rising to stave off a wave of pandemic-induced displacement. Newsom acknowledged as much at a July 14 event publicizing the state’s rent relief efforts.

“If we see mass evictions, we will have seen something we’ve never experienced in our lifetime, and that’s the number of people on the streets and sidewalks that will overwhelm,” the governor said. “That’s why this program is so important.”

An overnight safety net

When California created its Housing Is Key rent relief program early this year, it followed the lead of Texas and other states by hiring the Mississippi consulting firm Horne LLP to run its online applications. At first, the process took about two hours on a strong internet connection, required extensive income documentation and offered only rough translations in a few languages.

This spring, as the state worked to address those issues, things got more complicated. Counties and cities could choose different models to distribute funds. Option A counties let the state keep running the program, like in Contra Costa, San Mateo and Napa counties. Option B areas took over themselves, as in Alameda, Marin and Sonoma counties, plus the city of Fremont. Option C allows hybrid state and local programs, as in San Francisco, Santa Clara and Solano counties, plus Oakland and San Jose.

The result is a patchwork leaving thousands of people in limbo, unsure if old applications are still being processed or where to go for help with debt from certain months. In San Francisco, local officials are offering to pay rent after April 2021, but residents must fill out a separate state application for back rent before then. Those who applied to earlier city programs must complete a new application.

“The pronouncement of everybody’s gonna get 100% relief — it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny right now,” said Shanti Singh, communications and legislative director for advocacy group Tenants Together. “It’s got holes like Swiss cheese.”

When Medina’s corporate kitchen closed with the rest of the Bay Area last spring, there was no fallback plan for a disaster where thousands of people were suddenly unable to pay some of the nation’s highest rents.

As San Francisco’s unemployment rate spiked from 3% to more than 13%, Medina’s family scraped together savings to cover their $1,500 rent. Then she contracted the virus, as did her dad and brother back in the central Mexico state of Morelos. When they died, she felt guilty about not being able to send money home.

Last summer it all became too much. Medina and her husband split up. Debt added up, and she started selling the tamales. She applied for a program that she heard from a tenant group would pay 80% of back rent, then applied for a different program to repay 100%.

Medina received an email in late July saying that her application for the $9,000 in rent debt had been approved, but she hasn’t gotten any details since then, and she fears that her landlord’s patience is running thin. She’s still struggling to find more stable work with morning hours, when she can arrange child care.

“What am I going to do?” Medina said in Spanish. “I don’t want to stay in debt. I want to pay already — to get out of this.”

Some other persistent renters have started to get answers. Jackie Lowery lives in Contra Costa County, in an Antioch home that she and her husband rent with their son, his wife and her twin grandchildren. She called the state rent relief program twice a week after they applied in March.

The wait was long, she said, but the results were life-changing.

Lowery had retired after decades of work in refinery construction and was settling into remission from breast cancer when the pandemic hit. Her husband and son lost their jobs as security guards, and the family fell $10,000 behind on rent.

When Lowery finally heard this summer that they’d been approved for rent relief, months of stress evaporated. As she waited for the check to clear, she started looking for a way out of the rental grind with first-time home buyer programs — though those, too, can come with long odds as Bay Area home prices keep breaking records.

“Let’s face it, after this pandemic, I think a lot of landlords are going to be shy to even rent out anymore,” Lowery said. “The rental market, it’s not gonna change anytime soon.”

An invisible challenge

While the stories of renters like Medina reveal cracks in California’s COVID rent relief efforts, advocates are most worried about those still outside the system entirely.

“A big concern is the people I don’t see, that never make it to my office,” said Tiffany Hickey, an attorney with civil rights advocacy group Advancing Justice-Asian Law Caucus. “People just being afraid of that debt or who have moved on their own, or succumbed to the landlord harassment.”

Hickey’s office filed a formal complaint with the state last month over ongoing language access issues with its rent relief program, and officials say they’re still working to improve the process. In June, lawmakers made those who already left apartments, or “self-evicted,” eligible for rent relief, though advocates fear many will be hard to track down or fearful of retribution while searching for a new home.

One nagging challenge is that no one knows for sure how much tenants owe, or who exactly is behind. In San Francisco, a June city report gave a low estimate of $147 million and a high estimate of $355 million — a difference that could mean running out of rent relief money before many people apply.

A more systemic issue, said Vincent Reina, an associate professor of city planning at the University of Pennsylvania, is that housing assistance programs tend to leave out certain groups, in particular nonwhite renters. Reina found in a July report that rent relief applicants so far skew disproportionately white.

“We’re building on historic disinvestment in housing,” Reina said. “That very much means there are groups that repeatedly don’t receive any resources or are on the losing side of lotteries.”

Public officials continue to plead for anyone behind on rent to apply for rent relief. Dozens of community groups have been hired in different counties to help with outreach, though tenants and landlords say they’ve had mixed results getting help with applications. While most local governments are not yet publicly reporting how much rent relief money has been paid, a new state dashboard shows that its program has paid out a total of $242 million across California as of Aug. 3. San Francisco’s program also sent out its first checks totaling $2.7 million in late July, a spokesperson said.

Behind the scenes, bigger political conversations are happening about how rent assistance could be improved and potentially catalyze other social services reforms.

A primary concern for researchers like Reina is “shadow debt” impacting renters who ran up credit card bills or sacrificed other spending to keep paying for housing. The state is developing a plan to address $2.7 billion in utility debt, and lawmakers are debating measures to limit the impact of pandemic-era debt on credit scores and rein in debt settlement companies. Assembly Member Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland) said the scramble has also revived calls to consolidate applications for public benefits like food stamps, unemployment and rent assistance.

“We have to have a more streamlined way for people to access social safety nets,” Wicks said. “There’s been ongoing talk in this space of, ‘Can there be one portal?’ ”

For now, Medina is left to wrap her tamales at night. She sets out in the summer mornings to make deliveries.

Lately, as she juggles her cooking schedule with calls to tenant groups, she’s noticed a new problem: more competition from others going to extremes to make ends meet in an uncertain moment.

“La verdad es, hay mucha gente vendiendo comida,” Medina said.

“The truth is, there are a lot of people selling food.”

Lauren Hepler is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: lauren.hepler@sfchronicle.com; Twitter: @LAHepler