ARCHITECT PROFILE

Berkeley’s Andrew Fischer on mitigating wildfire risk

By Jordan Guinn CENTRAL VALLEY NEWS-SENTINEL

The risk of wildfires seems greater than ever. Years of drought and soaring temperatures are creating tinderbox conditions across the country, even in the Bay Area. And the rising demand for homes creates a need for new construction across the region.

So how can architects and designers plan for a future that’s more protected against the risk of fire?

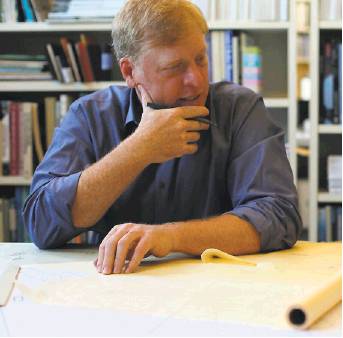

Architect Andrew Fischer fully understands the intricacies of building houses in the Bay Area’s physical and bureaucratic landscape.

Fischer and his wife, architect Kerstin Fischer, head Fischer Architecture in Berkeley, a firm specializing in designing custom homes and residential renovations throughout the Bay Area. Increasingly, the Fischers find the threat of wildfire affects their project designs — and these concerns are no longer limited to extremely rural sites. Rather, wildfire risk is an identified issue in well-established neighborhoods in many local jurisdictions.

And being aware of the risk of wildfires may be more important than ever. Experts project a total of about 1.2 million new homes to be built in California’s highest wildfirerisk areas by 2050.

In this interview with the San Francisco Chronicle, Fischer talks about fire-resistant designs, the future of fire protection and steps people can take to prepare for the worst-case scenarios.

Q: How do you safely approach building or rebuilding in high fire risk areas?

A: Building in fire risk areas starts with careful consideration of the site design. For example, what’s the existing site access like for evacuation? What is the quality of the existing road? Or if a new private road, or long driveway is needed, how wide does it need to be in order to provide good, safe access? Also, it’s important to get a handle on how existing vegetation will affect the design. Cutting back vegetation is a good start, trimming and managing trees, shrubs, grasses to create a defensible space around the house. Another important consideration is the roof design, which we feel should be simple, not complicated with nooks and crannies where dry leaves and such can accumulate. Eave overhangs and exposed gutters can be problematic in terms of fire safety — if a wildfire is present, heat and flames collect under eaves, which can in turn ignite dry leaves and debris that has collected in gutters.

So in general, we try to limit, or omit, such building elements in our designs. Of course selecting non-combustible or ignition-resistant exterior building materials and finishes is key.

Building in an area that has already been affected by a wildfire is a little bit different. Fire risk in such locations is not gone, but is tempered because usually much of the fuel has been eliminated, or at least managed by whatever fire has occurred. Also, oftentimes jurisdictions take the opportunity of this “clean slate” to upgrade infrastructure, such as undergrounding power lines, and widening roads where possible, which makes these areas safer for the future.

Q: Which materials are best for fire resilience, and how to design with them?

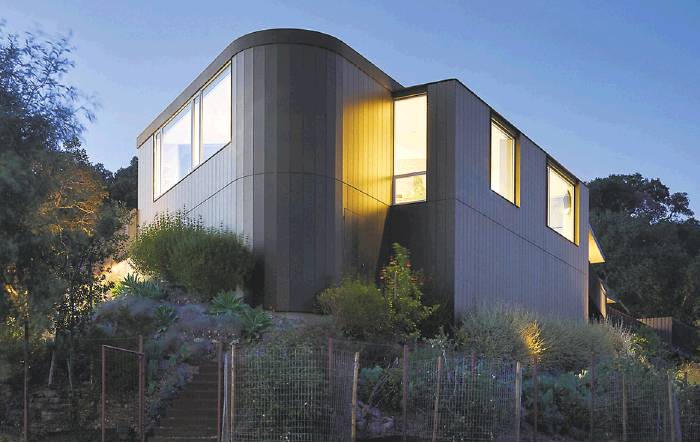

A: In fire-prone areas, we are mandated by the California Building Code to use non-combustible or ignition-resistant exterior building systems and materials. Some examples are stucco, cement or steel panels. Our office is wrapping up construction on a new contemporary home in the Napa Valley where we’ve used concrete block as our primary building material — it’s the structure, exterior finish, and the interior finish as well. With careful detailing, even simple materials like these can be finessed to create beautiful and resilient architecture.

Q: How should one navigate the complex issue of home insurance when rebuilding in fire zones?

A: There are really two different issues here. The first is the question of how do you manage reimbursement or replacement cost from your insurance company in the case where you’ve lost your home in a wildfire. Through our dealings with insurance companies as we help our clients navigate these fire rebuild complexities, we’ve learned that replacement cost does not necessarily mean you need to rebuild exactly what was lost. I think a lot of people do not know or understand this.

In fact, it’s possible to rebuild with a design that is entirely different from what was lost, and oftentimes that’s precisely what should be done, so that the home and site design can be optimized for fire safety. Another thing to remember when you are negotiating replacement cost with your insurance carrier as you rebuild is that the process can continue into the construction phase in order to correct for inflation and unforeseen costs. My advice is to keep the door open with your insurance company during the rebuild process; don’t leave it as a “one and done” transaction.

I think the second issue is more common right now, and that’s getting fire insurance in high risk areas. You’ll likely need to shop around, and be prepared for some frustration. I have friends who live in the Berkeley Hills whose policies have not been renewed because they live in a high fire risk area. Consumers are often only exposed to larger insurance companies. It’s worthwhile to look for insurance companies that are not overrepresented in the area.

Q: What parts of the Bay Area do you believe to be most at risk for wildfires?

A: Oh wow. Well, there are places all over the Bay Area where it feels like it’s just a matter of time, unless measures to mitigate risk are taken. I look forward to seeing continued efforts to manage wildfire instability among all stakeholders in these precious areas. It will take everyone’s help to keep our fire zones as safe as possible.

And it will take long-term dedication to managing the risk of wildfires into the future. I think about the fire that wiped out a good portion of North Berkeley in 1923. After that fire, a handful of local architects, including Bernard Maybeck and John Hudson Thomas, began experimenting with non-combustible and ignitionresistant materials.

Maybeck developed custom concrete shingles as siding for his buildings, and Thomas designed a grand home up in the hills that’s made of cast-inplace soil cement — using a mix of Portland cement and local soils. Because these measures were not mandated or adopted by the building code, they didn’t stick, and rebuilding happened without fire safety as a primary consideration. Now that same neighborhood is one of our area’s most at-risk for another firestorm. Decisions — or rather the lack of decisions — made nearly a century ago have us back where we started.

Q: What’s one of the most logical fire regulations you’ve encountered in the Bay Area?

A: The California Building Code has a section dedicated to buildings in fire zones, called the “Wildland Urban Interface” — areas where buildings and wildland vegetation directly intermingle. Most of our projects are in the WUI. Lots of established neighborhoods in towns and cities throughout the Bay Area have this classification. WUI regulations that mandate non-combustible ignition-resistant exterior materials and maintaining defensible space feel most logical and effective from my perspective.

Ideally, these two concepts minimize the spread of fire, and minimize the ability for a building to catch on fire. But every project is unique, and sometimes local building officials will take certain site specificities into consideration and allow substitutions or tradeoffs in order to approve a project.

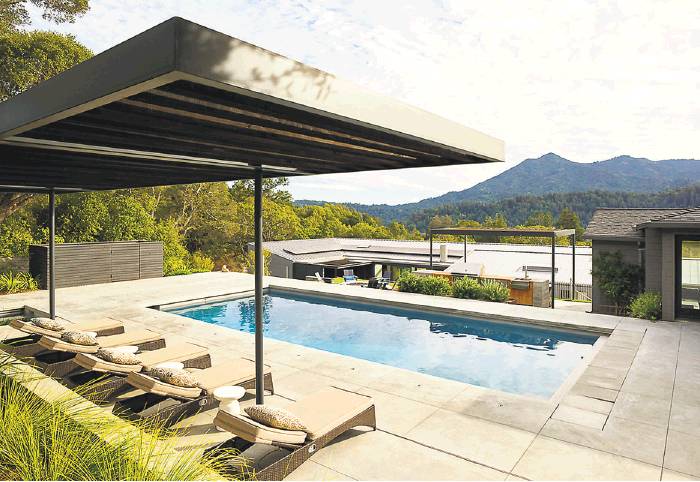

We’ve had fire departments allow swimming pools to be used as the source for an onsite fire hydrant, and had one project where a too-narrow access road was mitigated by using fire-rated construction, which was a step up from WUI requirements.

It’s encouraging when local officials join us in thinking creatively about solutions. Everyone wins.