With less need to yell, birds’ singing is best in decades

By Nora Mishanec

It was just after sunrise at Lobos Creek in the Presidio, and ornithologist Jennifer Phillips was crouched low in the dunes, waiting for sparrows. She inched forward, microphone in hand, the early morning silence broken by birdsong and the distant rumble of traffic.

On that morning and many others since the start of the pandemic, Phillips roamed the Presidio’s coastal sage scrub in search of whitecrowned sparrows, one of the Bay Area’s most common avian inhabitants, known for its distinctive, trilling warble.

Phillips was astonished by what she heard. The birds sang more softly in the relative quiet of the pandemic-stricken city. They began using a lower register — a more seductive trill — that hadn’t been recorded locally since the 1950s.

As the hum of human activity diminished, the birds filled the silence with ever-more complex songs, their trills reinvigorated by the absence of urban noise.

The softer songs signify just how quickly birds adapt to changes in their environment, a trait that has broader implications for their survival in urban spaces. No longer straining to be heard over the din of traffic, the singing sparrows were better able to attract mates, ward off rivals and defend their territory.

“When they sing softer, they can sing a wider range of notes, a sweeter song you might say,” observed Phillips, a researcher at California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo. She collected similar recordings of the sparrows at Point Reyes National Seashore and the Berkeley Marina, in addition to the Presidio in San Francisco.

Phillips and her collaborators at Cal Poly may be the first researchers to document the coronavirus pandemic’s impact on songbird behavior. Their research, published in the journal Science this year, found that the sparrows sang about 30% quieter during the pandemic compared to previous decades.

“It’s pretty exciting that they responded so fast to the sudden change in the sound of the city,” she said.

The findings could have broad implications beyond birds. Conservation efforts have historically focused on restoring lost animal habitats, but have rarely considered the detrimental effects of urban noise. It’s a factor worth considering, Phillips said, especially as California contemplates a future full of electric cars.

“Other birds that have been driven out of urban areas could be brought back if more people drove quiet cars,” Phillips said.

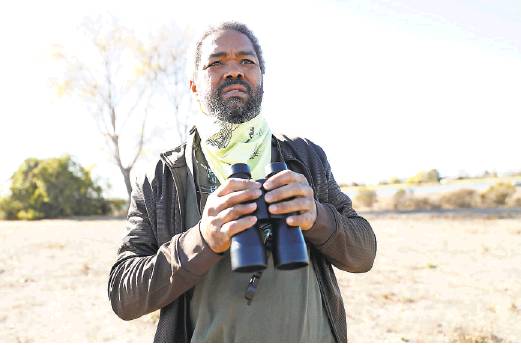

It’s not just birds that stand to gain from city planning that takes noise into account, said Clay Anderson, an avid birder and youth coordinator for the Bay Area Audubon Society.

“We all benefit from being quieter,” he said.

Anderson is a frequent visitor to Oakland’s Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline, known in birder lingo as his “patch.” He’s noticed more people turning to nature as a refuge during the pandemic, but he wishes the Bay Area’s 7 million human inhabitants thought more about their daily impact on the animals around them.

White-crowned sparrows are good at adapting to human activity, but their ubiquity should not be taken for granted, Anderson said.

He cited the tri-colored blackbird and the passenger pigeon as just two examples of bird species that appeared to thrive in the bustle of the Bay Area before dying off in droves. The now-extinct passenger pigeon was once the most abundant bird in North America. The tri-colored blackbird, once a California mainstay, is listed as an endangered species.

For now, the sparrows are flourishing. But the renewed complexity of their songs may be short-lived. Traffic has started creeping back to prepandemic levels as Bay Area residents venture out amid reopening efforts and stay-athome fatigue.

The sparrows that hatched during the pandemic, however, may retain their full range of singing ability, Phillips said. Young birds learn the warbling trills of their parents and neighbors during the formative months in the nest.

“They crystallize as singers and that’s the song they sing for the rest of their lives,” Phillips said.

The question is whether that will hamper the young sparrows come spring, when the world may have returned to its loud, pre-pandemic routine.

“Will they be able to breed successfully singing songs mismatched to their habitat?” she said. “Or will they adjust?”

Nora Mishanec is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: nora.mishanec@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @NMishanec