Bears, elk, sharks crown wildlife surge

The recovery and revival of more than a dozen major wildlife species in California could be one of the greatest overlooked stories in a generation.

Wildlife species, including bears, elk, sharks, whales, eagles and others are at their highest populations in more than a century, a direct result of habitat protection and crackdowns on commercial take and poaching, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“The general narrative out there is mass extinction, wildlife is struggling and helpless animals, and it’s just not the case,” said department spokesman Peter Tira. “Certainly there are challenges, but when you look close, it’s just one terrific story after another.”

In the state budget signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom last month, the governor increased wildlife officer positions to 465, the highest number in state history. “Amid the ebb and flow of wildlife cycles, there are good things happening,” said department Capt. Patrick Foy.

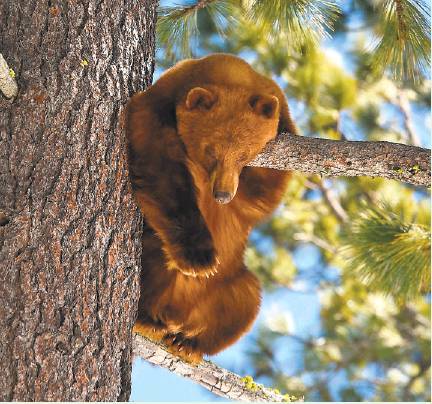

Bears: The department estimates the bear population at about 40,000. That’s up from 10,000 in the 1980s. At the time, the department believed the population was not limited by habitat but by organized rings of poachers who set up illegal networks to sell bear parts, via Los Angeles, at high profit to consumers in Southeast Asia. The department conducted a series of undercover operations and busts.

Elk: A well-known story is that in 1874 the tule elk population was down to a single breeding pair, which lived in a rancher’s pen in the San Joaquin Valley. Those elk became Adam & Eve. A century later, in 1977, seven elk were introduced to the Grizzly Island Wildlife Area in Solano County. As that herd grew, it helped provide 1,200 transplants to create 21 herds, paid for by money from hunting licenses and tags. The total population in California has grown virtually every year for 20 years and now numbers about 5,800.

Sierra bighorn sheep: The Sierra bighorn sheep is the king of the High Sierra — lean, muscular and adept on the high canyons, crags and ledges. Yet the Sierra bighorn was nearly wiped out — down to 100 animals in the late 1990s — after exposure to disease from domestic sheep and predation by mountain lions. The latest counts verified more than 600 animals. Sheep were banned from their range and the Department of Fish and Wildlife identified and killed 24 lions that were targeting bighorns.

Mountain lions: The biggest mystery across the land is how many mountain lions are out there. To provide a reliable answer, the department has undertaken a multiyear survey. The preliminary consensus is that the number is high, perhaps double or triple the estimate from the 1990s. Sightings and encounters have occurred in recent years in areas across the state where lions were unheard of. The logic is that as lions give birth, the older males force out the yearlings to establish their own turf, and that gives rise to a natural expansion of population.

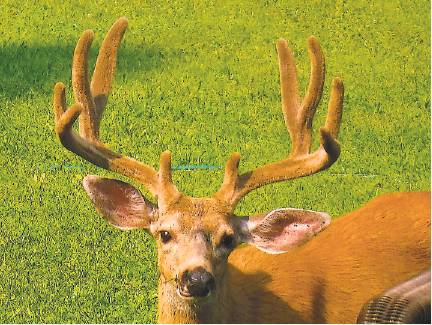

Black-tailed deer: After going through a crash where the statewide deer population fell to 445,000 in 2010, deer populations have stabilized at about 500,000, with the latest count at 532,000, DFW said. The makeup of the herds, however, has transformed. The once great migrations in early winter, from the High Sierra to the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys, is gone forever, blocked by roads, cities and too many people. Deer now largely live at golf courses, parks and backyards adjacent to greenbelt, never traveling more than 5 miles in their lives, according to GPS collars, with the expanding lion population and predation one of the limiting factors.

Coyotes, wolves

Coyotes: Coyotes continue to expand into cities at a rate never seen before. Some 20 years ago, there were no coyotes in San Francisco. The first one arrived from Marin via the Golden Gate Bridge. Recent estimates suggest they number 40 to 70, and the population is growing. In Los Angeles, so many coyotes live in city parks that 39 people have been bitten in the past five years, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Wolves: The first wolf in 87 years in California migrated in from Oregon in fall 2011. Others have followed, and some have mated. The Lassen Pack is believed to have five adults and a yearling, according to wildlife cams. The Shasta Pack may have dispersed, but in 2015, trail cams verified five pups. One wolf, OR-54, collared with a GPS transmitter, logged 6,644 miles in three years. The department isn’t sure how many wolves are established in California because of how far wolf packs range.

Sharks, whales, otters

Great white sharks: Roughly 200 to 400 great white sharks were estimated off the Bay Area coast in the 1990s. Now there are 2,400, according to a study authored by 10 scientists. Off Seacliff State Beach this summer, there have been so many juvenile great white sharks that we call it “Shark Park.” Note that it is illegal to use any method to attract the great white sharks, as I once did with a variety of methods before federal law made it illegal.

Humpback whales: Seniors would remember the “Save The Whales” crusade of the 1960s, when humpbacks were on the brink. Well, it worked. The eventual moratorium on commercial whaling is the key to their comeback, with 80,000 humpbacks now worldwide and 20,000 on the Pacific Coast, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Gray whales: There are now so many gray whales, 26,000 on the Pacific Coast, that NOAA calls it “optimum sustainable populations.” There were fewer than 2,000 in the 1960s.

Sea otters: Fur trappers tried to wipe out these cute little guys, but missed about 50 at Bixby Creek Cove south of Carmel. In the 1930s, the otters were discovered and protected. This year’s counts will be announced in a few weeks, but for the past three years, the average population has topped 3,090, which is the threshold for delisting. Nowadays, great white sharks are their biggest threat.

Eagles, falcons, waterfowl

Bald eagles: The pesticide DDT made the eggs of many birds too thin to withstand nesting, and in 1963, 417 nesting pairs were counted in North America. In the 1970s, bald eagles were in danger of extinction, and in California, not a single bald eagle was verified south of Shasta Lake. The Predatory Bird Research Group estimates 21 mated pairs in the Bay Area, 200 baby chicks, and 40 to 50 nesting pairs in the greater region, and statewide, they exceed 1,000 during winter migrations. The latest official count for North America, announced in 2007 when delisted, was 9,789 breeding pairs.

Peregrine falcons: The world’s fastest creature, with a flight speed that can top 200 mph in a dive, was believed to be reduced to two nesting pairs in the 1970s, courtesy of DDT. In the Bay Area alone, PBRG verified 41 known nesting sites. In one study, they checked 18 nests and found 45 young.

North American flyways: The total duck population, counted in a vast survey of aerial flights, was estimated at 41.2 million breeding ducks last year, which is 17% above the long-term average over the past 60 years, reported the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Tom Stienstra is The San Francisco Chronicle’s outdoors writer. Email: tstienstra@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @StienstraTom