S.F. HOMELESS PROJECT

Recent increase makes Oakland No. 1 in state

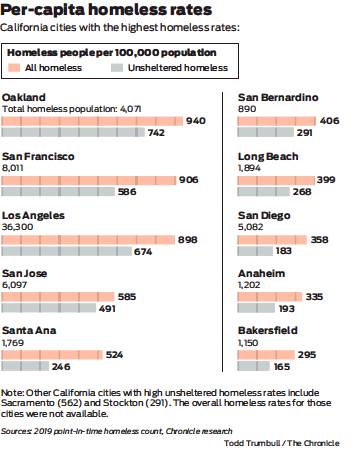

By Sarah Ravani and Joaquin PalominoSan Francisco is known for its swelling homeless population, but Oakland has surpassed its neighbor across the bay, and other large cities in California, in a key measure: the concentration of homelessness compared with the number of people living there.

A Chronicle analysis of city numbers on homelessness collected this year found that there were an estimated 742 unsheltered homeless people in Oakland for every 100,000 residents — the highest among the state’s largest cities. The rate is four times that of San Diego and 27% higher than San Francisco’s.

The story is much the same for total homeless, including those in shelters. Los Angeles has the largest homeless population in the state by a wide margin, but on a per capita basis, Oakland, where the number of people living on the streets or in temporary shelters grew 47% from 2017 to 2019, now has more.

Oakland’s two-year increase was among the biggest of any California city. In 2017, San Francisco had more homeless people than Oakland per capita, but the crisis is spreading.

Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf said the primary cause of homelessness in the city is a shortage of housing.

“I think what went wrong here is that Oakland has finally come on the map as a highly desirable place to live,” Schaaf said. “We have new people moving in here, and we aren’t building new housing for them quickly enough. We have not figured out how to replace the loss of redevelopment financing to build more affordable housing.”

Oakland officials point to what they say is an aggressive, multifaceted strategy to address the crisis that includes community cabin sites, RV safe parking and affordable housing. The city is also setting aside funds for future Navigation Centers and launching a pilot program of self-governed encampments to be run by grassroots organizations.

But the shocking growth in homelessness since 2017 has many advocates questioning the city’s response by calling it a temporary solution that won’t have a lasting impact.

Here’s a look at the scope and nature of the problem in Oakland, and what is being done to address it:

How many homeless people are there in Oakland?

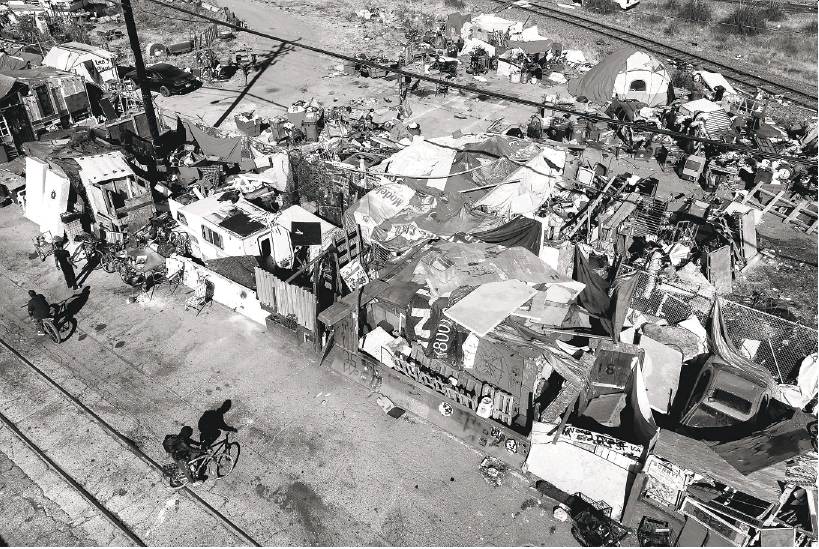

In 2019, Oakland made up nearly half of Alameda County’s overall homeless population. The city had an estimated 861 sheltered homeless people and 3,210 unsheltered people compared with 859 and 1,902, respectively, in 2017.

The 47% increase was a stark reminder of the growing number of people in Oakland who are struggling to remain housed. While some parts of California experienced similar spikes, none of the state’s 22 cities with more than 200,000 residents reviewed by The Chronicle had a higher concentration of homeless people than Oakland — both in total, and those living on the streets.

Sacramento and Stockton have not yet released their total homelessness figures for 2019, but their per capita unsheltered populations, which are available, were far lower than Oakland’s. Homeless counts track those living on the streets as well as those in temporary shelters — adding up to the total number of homeless.

“People are staying homeless longer, and fewer people are leaving the system to housing,” said Elaine De Coligny, executive director of EveryOne Counts, the organization that does the official homeless count for Alameda County. “The pace at which people are moving back into permanent housing has slowed. The pace at which people are becoming homeless for the first time has gone up, and the length that people are staying homeless before they move back to housing is going up.”

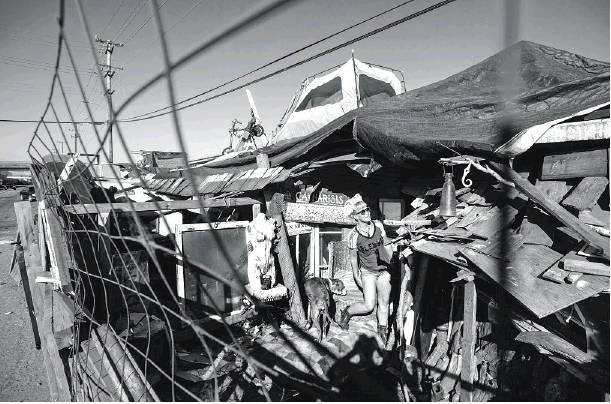

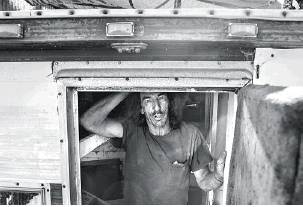

Oakland has an estimated 60 encampments where about 730 people live. The city currently provides portable toilets, wash stations and garbage pickup at 22 of the encampments. County numbers show a growing number of residents living in vehicles — 23% of the county’s overall homeless population live in a car and 22% live in an RV. Sixtythree percent of the population have been homeless for more than a year.

“The stark increases seen in Oakland over the past two years justify an increase in resources from Alameda County and the state,” said Joe DeVries, the assistant to the city administrator. “Our entire region has witnessed a devastating increase in homelessness, and any improvement will be the result of a regional shared collaboration.”

The point-in-time survey, which is conducted across the country and reported to the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, does not include people temporarily living in a motel, on a friend’s couch or in other less-thanstable circumstances.

Because the count is done on the last week of January, during the peak of winter, the number of people sleeping outdoors is also likely at its low point.

“There are a lot of people who are unhoused who are not visible because they are not on the street,” said Margaretta Lin, executive director of Just Cities/ Dellums Institute. “We have families riding the buses at night for shelter. They’re sleeping on people’s couches and are one step away from being on the street.”

How much is it growing and where are they coming from?

Some of Oakland’s street and shelter dwellers are newly homeless, De Coligny said. Most are from the county. In 2019, the numbers showed that 78% of Alameda County’s homeless population were county residents, according to EveryOne Counts.

Schaaf said the trend has continued in Oakland. The recent numbers in Oakland show her that close to 15% of the homeless population is from outside of the city.

“As I talked to our unsheltered residents on our parks and on our sidewalks, I meet people that went to the same high school I went to, who actually grew up in the very neighborhood where they are now living in that local park,” she said.

What shelter and service options does Oakland offer?

Oakland offers year-round a total of 457 beds in 15 shelters — some of which are outside the city, including in San Leandro. The city’s biggest shelter, St. Vincent de Paul, has 100 beds. East Oakland Community Project and St. Mary’s Shelter offer 10 and 28 beds, respectively, during the winter. The city also has five community cabin sites that provide temporary housing for six months. A sixth site is expected to open in several weeks near Chinatown.

Schaaf said the city plans to add 700 more shelter beds by the end of the year through the expansion of the Henry Robinson Center, the Holland, community cabin sites and RV safe parking sites. When the pointin-time count was taken in January, the city had only two community cabin sites and has since opened three more, as well as the RV parking site, she said. The city has 1,400 permanently affordable housing units that are approved for development or are currently under construction.

Building affordable housing isn’t happening fast enough, Lin said.

“It takes time to build those new traditional housing units, so what we need is an interim strategy of being able to develop innovative and quick housing prototypes like tiny homes and mobile homes and container homes,” Lin said.

Candice Elder, executive director of East Oakland Collective, said many homeless people have jobs but don’t make enough income to pay rent.

“I know of people who are in-home care service providers, who are nurses and teachers,” she said. “There are folks who do delivery jobs.”

What is Oakland’s plan to expand those offerings?

Oakland has budgeted $87.4 million for homeless services and affordable housing over the next two years. That’s the most it has ever put toward homelessness, said Council President Rebecca Kaplan.

The City Council put $400,000 toward offering sanitation services at encampments. The city plans to spend $600,000 for alternate housing solutions, including tiny homes. The budget also designated about $300,000 to fund a highlevel administrator to focus on homelessness.

The city plans to put $3 million toward Navigation Centers, but the funds are contingent on grant eligibility.

Is Oakland doing enough?

Advocates say the city is focusing too much on temporary solutions. Homeless people say Oakland’s options — community cabins and RV parks — don’t give them enough time to get back on their feet.

“People are transitioning back onto the streets,” Elder said. “But they can’t go back to where they were living because once the city opens that (community cabin) site … the safe parking site, they evict all the encampments. It just shuffles people across the city to someone else’s neighborhood, in front of someone else’s business.”

Markaya Spikes has lived in a tiny home outside the Home Depot for nearly three years. Her home — a red 8-by-10-foot space that has a loft inside, space for a television and a couch — was built by students at the Oakland School for the Arts. Spikes, 38, prefers it over a community cabin because the cabins don’t feel like a home. Unlike the community cabins, Spikes’ home has a heater. She can cook. She has a microwave, toaster oven and television.

“I have a house. I have an actual house,” she said. Community cabins “are out of the question. They are sheds.”

Her neighbor, Elizabeth Easton, 66, feels the same way. Easton has a tiny home and a trailer, but her trailer wouldn’t qualify for an RV parking site because it’s not a functional vehicle. She said the city’s strategies only result in her eviction from wherever she sets up her trailer.

“Don’t evict us,” Easton said. “What are we doing?”

Officials say more emphasis needs to be put on prevention.

“We have got to stop people from becoming homeless, losing the housing they have,” De Coligny said. “We have to go make more permanent places for people to go that they can afford available or we are never going to fix this prolem. Shelters are an important response, but they are not a solution to homelessness.”

Sarah Ravani and Joaquin Palomino are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: sravani@sfchronicle.com, jpalomino@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @SarRavani @JoaquinPalomino