OURSF

THE FIRST MISSION MURALS

The 1970s: We found photos of Latino artists’ epic artworks, and many are still there

By Peter Hartlaub

Palm trees were planted in the Mission District in early 1971 — a clear attempt by city leaders to give the struggling working-class neighborhood more of a Santa Barbara vibe.

But the locals had their own makeover planned; one that didn’t involve pretending to be something that they were not. The first high-profile murals appeared in the local media that same year, beginning a history of public art that has defined the district.

The Chronicle’s first article about Mission District murals was a Thomas Albright art review on Nov. 18, 1971, celebrating new storefront murals by San Francisco artists Robert Crumb and Spain Rodriguez. Albright returned in 1974 to cover the introduction of three even more epic pieces, all panoramic public art created by teams of Latino artists.

The most impressive work was designed by Jesus Campusano — an L-shape mural filled with subversive imagery built in a very unexpected place.

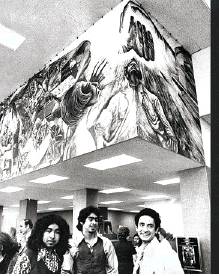

“By far the most extraordinary of these works is a 90-foot-long mural executed by a team of eight artists,” Albright wrote. “No less extraordinary is the fact that it was commissioned by, and hangs above the teller windows of, the 23rd and Mission branch of the Bank of America.”

The Bank of America mural featured a melting pot of Latino figures, including Native Americans in traditional dress, Mission High students, BART construction workers, street gang members and a doctor cutting the umbilical cord of a baby.

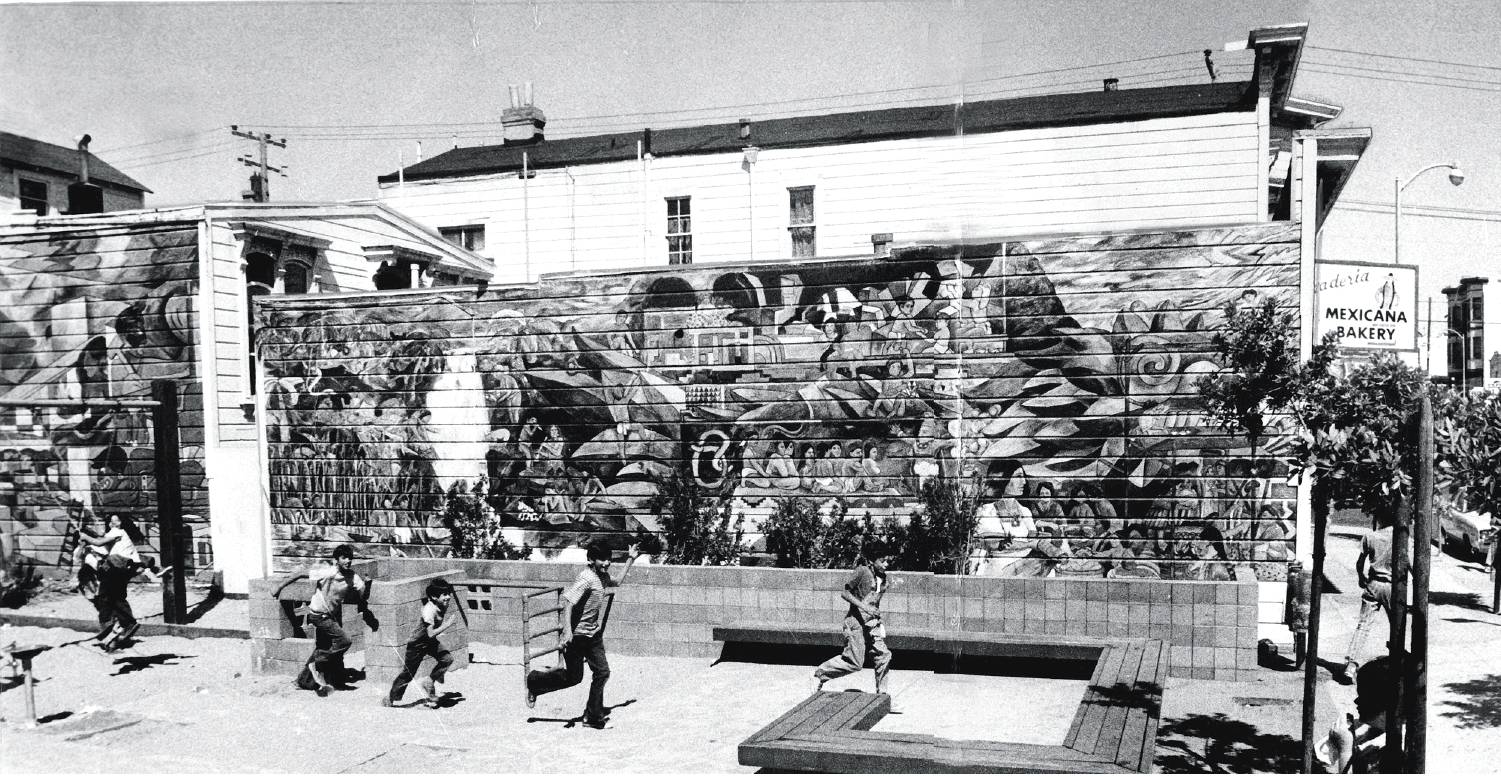

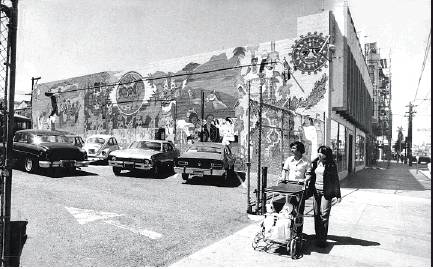

The other 1974 murals were equally ambitious. Michael Rios designed a mural with Aztec jungle themes at a minipark near 24th and Bryant streets. And four Latina women, calling themselves the Mujeres Muralistas, painted a surreal scene with horses, gods and cartoonish figures on a parking-lot wall near Mission and 26th streets.

Walk in the triangle between those three mural locations in 2019, and you’ll pass by more than 100 murals as well as the Precita Eyes Mural Arts and Visitors Center. No one is taking pictures of the palm trees on a Monday early afternoon, but there are several tourists shooting photos in Balmy Alley and Clarion Alley in the Mission District, two of the most concentrated collections of murals in the city.

The parking-lot mural by the Mujeres Muralistas is gone; now it’s a dull military green rectangle except for a few words advertising the Laundromat on the other side of the wall.

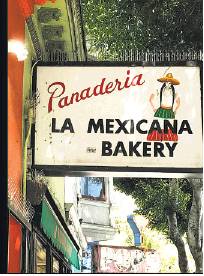

But the minipark mural still exists in 2019 as it did in 1974, with a lot of chipped paint but still enough left to see the most dominant figure — a green feathered serpent that has been protecting the Mission for two generations. Trees that were saplings in 1974 cast shadows over nearby businesses, hiding the fact that the Panaderia Mexican Bakery sign next to the park is still there, looking unchanged after 45 years.

The biggest surprise is in the Bank of America on 23rd and Mission. The branch has built glass cubicles and waiting rooms, and other changes for increased security. But everything seems to have been designed to continue showcasing the mural, which hasn’t aged a day.

Large figures of the revolutionary Emiliano Zapata and poet Rubén Dario looking stoic behind bars are vivid, as if they might jump off the wall and start a new political movement at any moment. Political sentiments on the wall (“Our sweat and our blood have fallen on this land to make the other men rich”) carry, if anything, even more meaning

The beginnings of a public art movement, looking as relevant as the day the paint touched the blank canvas.

Peter Hartlaub is The San Francisco Chronicle pop culture critic. Email: phartlaub@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @PeterHartlaub

“By far the most extraordinary of these works is a 90-foot-long mural executed by a team of eight artists.”

Thomas Albright, San Francisco Chronicle review of mural on Mission and 23rd streets, Nov. 18, 1971