LURKING DANGER

Toxic chemicals that poisoned Burrillville wells could be part of a burgeoning public-health crisis

By Alex Kuffner Journal Staff Writer

ABURRILLVILLE rmand Collins can’t help but think that the cancer that caused his wife Lucia’s death last month may have been linked to the contamination of their water supply.

She was 67 when she succumbed to breast cancer on April 8.

“She was never sick. She didn’t do any of the bad stuff like me,” Collins said as he smoked a cigarette on the back steps of his duplex on Mill Street. “It just makes me wonder.”

In September 2017, the Rhode Island Department of Health discovered that the well that serves Collins’ home and some 34 others in Oakland village was contaminated with a class of widely used chemicals that many experts believe is contributing to a global public-health crisis. Follow-up tests in the neighborhood a few weeks later found the same substances in six private wells.

The human-made compounds that fall into the family of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFASs, are added to foams used to fight fires and applied to cookware and packaging to keep food from sticking and to carpets and furniture to prevent staining.

High exposure to the compounds has been shown to cause developmental disorders in children, raise the risk of cancer, interfere with hormonal production and increase cholesterol levels, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

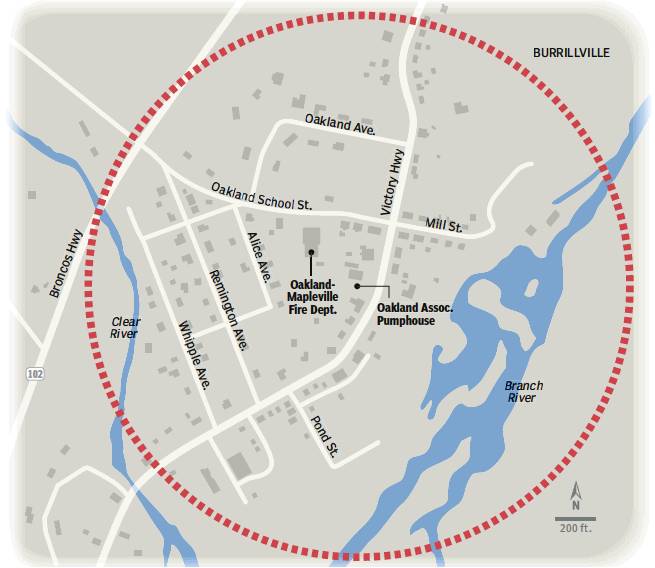

The testing done in 2017 was the first time authorities looked for PFASs in the Oakland aquifer. The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management traced the contamination back to firefighting foam that leached into the ground from the Oakland-Mapleville Fire District, but it’s unknown when the water became tainted.

After the test results were released, the DEM organized deliveries of bottled water to the former mill village located between the Clear and Branch rivers, and a new water line from the Harrisville Fire District is set to be completed this summer at a cost of nearly $3 million.

But while the long-awaited project will solve the neighborhood’s problem, broader questions remain largely unanswered about PFASs. What concentration in drinking water is safe for human consumption? How many other drinking water systems may be contaminated? Is the federal government doing enough to protect public health? What about Rhode Island authorities and their counterparts in other states?

The contamination in Burrillville was caused by a kind of foam that may be found in fire departments, airports and other facilities throughout Rhode Island. Even a small amount of it could have rendered the wells in Oakland unsafe to use.

“It gives you a sense of the scale of the problem across the state and the nation,” said Rainer Lohmann, a University of Rhode Island professor and co-leader of a federally funded research center on PFASs.

Invented in the 1930s, fluorinated chemicals were heralded for their ability to repel oil, water and grease.

Within two decades, DuPont had started using one of them, known as PFOA, to make Teflon, while 3M was using another, PFOS, in Scotchgard. Soon, the compounds were shown to be effective in smothering petroleum fires, enabling foams to spread more easily and form tighter caps over flammable liquids.

Today, there may be as many as 3,000 substances in the family that are used in everything from microwave popcorn bags to rain jackets to some dental flosses.

“To make a long story short, it’s everywhere,” said DEM assistant director Terrence Gray.

The chemicals have proven to be problematic because they are water-soluble, don’t break down in the environment and can accumulate in human bodies over time. They can be breathed in through dust and, to a limited extent, absorbed through the skin, but the main risk comes through food and drink consumption.

The Environmental Working Group, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, has estimated that up to 110 million Americans have been exposed to the compounds in their drinking water.

The highest-profile cases surrounding PFASs have arisen in Minnesota and West Virginia, in the vicinity of factories that manufactured the chemicals and have contaminated water supplies in neighboring communities. (Both PFOA and PFOS were phased out as a result.)

Military bases, where large quantities of firefighting foams are used, have also polluted groundwater aquifers. The U.S. Department of Defense has documented contamination, or identified its potential, around 401 installations around the nation. The list includes Joint Base Cape Cod in Bourne, Massachusetts.

The compounds are so potent that even a single incident in which firefighting foam is used can pollute groundwater. Last October, after a tanker truck tipped over in Providence, spilling some 10,000 gallons of gasoline, so much foam was used to contain the liquid that the white mounds looked like snowbanks rising up to the windows of cars.

Cleanup crews washed the foam into storm drains that eventually empty into the Providence River, and the chemicals dissipated in the flushing of Narragansett Bay in a matter of weeks, according to tests carried out by Lohmann’s lab.

But the story could have been different if the spill had taken place near drinking-water wells.

“If that incident occurred in some place like Glocester, we would have had significant contamination,” said Nick Noons, principal sanitary engineer with the DEM. “We would have had a big problem on our hands.”

The chemicals are unregulated by the federal government, despite repeated calls from environmental and public-health groups. The EPA, which enforces the federal Clean Drinking Water Act, has yet to put in place a legally enforceable “maximum contaminant level” for PFASs, only going so far as tightening recommendations for safe concentrations of the chemicals.

The revision came in May 2016, when the agency lowered a “health advisory” level to 70 parts per trillion (ppt) in total for PFOS and PFOA, the two compounds that have been the main subjects of the growing body of research into the dangers of the family of chemicals.

That level of concentration is roughly equivalent to 70 grains of sand in an Olympic-size swimming pool, says Noons.

It wasn’t until six years ago that the first tests for the substances in drinking water supplies in Rhode Island were carried out.

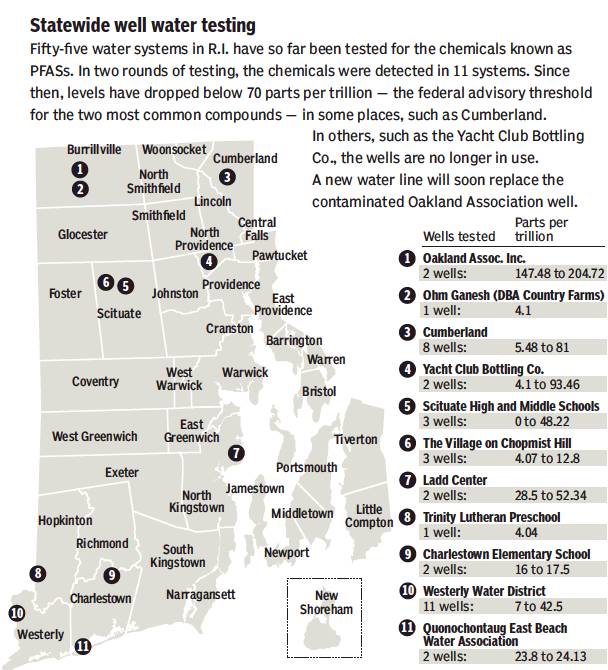

As required by the EPA, all large water systems — those serving more than 10,000 people — and a sample of smaller systems, 15 in all, carried out tests for PFOA, PFOS and four other compounds between 2013 and 2015.

Only two systems, Westerly and Cumberland, showed the presence of the chemicals. Both were below the EPA advisory level at the time, and in subsequent testing, the levels have dropped. The levels at several wells in Westerly, which ranged as high as about 40 ppt, have most recently hovered around 10 ppt, and the levels at a well in Cumberland, which were as high as 80 ppt and are believed to have been caused by plumbing tape on a pipe, were down to about 20 ppt, according to the health department.

In the summer of 2017, the department initiated its own round of testing statewide, prompted in part by the emergence of widespread contamination in Vermont and New Hampshire near factories that used the compounds. Working with researchers at Brown University and the DEM, the agency focused on 40 small public water systems — those serving fewer than 10,000 people — as well as schools and childcare facilities, all located within a mile of potential sources of contamination, such as firefighting training facilities, manufacturing plants and landfills.

The tests looked for nine PFAS compounds and detected them in eight places scattered around the state, but only one, the Oakland Association — the water system serving Oakland village — had numbers that exceeded the EPA advisory level. In three tests conducted between Sept. 14 and Sept. 29, the combined levels for PFOS and PFOA came back at 88, 69 and 114 ppt. But other PFAS compounds were also detected. When they are included, the total contamination ranged as high as 205 ppt.

With the six additional wells factored in, an estimated 175 people have been affected by the contamination. While they can shower with well water, they cannot use it for drinking, brushing their teeth or food preparation. Boiling water isn’t a solution, as it only concentrates the chemicals. So the DEM has been delivering water every two weeks to homes in the neighborhood.

Based on soil and water samples, the agency has also concluded that the Oakland-Mapleville Fire District is responsible for the contamination. The six private wells that were contaminated include the one at the district's firehouse at 46 Oakland School St. The five others, as well as the Oakland Association's, abut the department's property or are located nearby. The highest contamination levels were found in samples taken next to the station.

The chemicals leached into the groundwater from a storm-water infiltration field next to the firehouse, just north of the Oakland Association’s pump house. It’s unclear, however, if the substances leaked from containers of foam concentrate that were stored in the station’s garage or were washed from hoses or drained out of equipment after off-site training, said Noons.

The contamination happened after 2002, when the fire station was built, but there’s no way to narrow down the timing any further, according to Noons. Messages left with the department’s fire chief were not returned.

Richard Nolan, the operator of the Oakland Association and tax collector for the fire district, said he's not so concerned about the contamination, pointing out that if the water was tested before the EPA lowered its health advisory level in 2016, then it would have been deemed safe to drink.

But the uncertainty is unsettling to Collins, a retired bus driver with the Rhode Island Public Transit Authority. He has stuck to bottled water for drinking since the test results came back and stopped growing vegetables in his raised beds because he couldn’t water them. But he worries that he, his late wife, and their daughter, who lives in the neighboring unit, were using the water before the contamination was discovered.

“How long were we drinking it?” he said.

The water at Rhonda Nightingale’s house on nearby Remington Avenue tested negative for the chemicals but, worried about the possibility of the contamination spreading, she and her boyfriend chose to hook up to the new line coming in from Harrisville. It will offer some peace of mind, but it will also mean that they will have to start paying water bills.

“We shouldn’t have to,” she said. “It’s not our fault. We didn’t do this.”

In one way, the Burrillville case is an example of how state officials are still learning about the chemicals. The Oakland Association’s well was selected for testing because of its proximity to a landfill and several former factories. State officials didn’t expect the contamination to come from the fire station.

So in another round of tests that is now underway, the health department is looking at water supplies near fire stations all around Rhode Island that may also be storing firefighting foam. They are also sampling wells near schools, because floor waxes sometimes used in school buildings contain PFASs. There is a possibility that low levels of the chemicals found in school wells in Charlestown and Scituate during the 2017 tests were caused by floor waxes that passed through septic systems into groundwater.

The major water systems in the state are also being retested. When the tests are completed in June, it will mean that 49 percent of community water systems and all schools with wells in the state will have been sampled for PFASs. Homeowners with wells, restaurants and others are also being advised to do their own tests if they are near places where the chemicals are found.

“I feel we are being quite proactive,” said June Swallow, chief of the health department’s Office of Drinking Water Quality. “We are seeking out areas of concern and carrying out testing. We are also notifying private-well owners and suggesting a path forward for them as well.”

But some environmental groups believe that the federal advisory level of 70 ppt is too high, that the EPA's current leadership is too close to industry and is acting without urgency, and that, by extension, Rhode Island authorities aren’t doing enough.

The Conservation Law Foundation and the Toxics Action Center in February petitioned the health department to adopt a state drinking-water standard for five of the most common PFAS substances. They recommended a total threshold for the five substances of 20 ppt — meaning that concentrations of all five together must be lower than that level. It is the standard adopted just last week by Vermont, which is considered a leader in working on state PFAS regulations.

Other states are also taking matters into their own hands. Massachusetts and New Hampshire are working on setting maximum contaminant levels for the compounds. New Jersey has moved to set standards of 14 ppt for PFOA and 13 for PFOS, which would be among the most stringent regulations in the nation.

The Rhode Island health department denied the request from the Conservation Law Foundation and the Toxics Action Center, writing that it “shares the Petitioners’ concerns about the potential impacts of PFAS in public water supplies” but “lacks sufficient quantitative and qualitative data upon which to base appropriate regulations.”

In response, state Rep. June Speakman, a Warren Democrat, introduced a bill this month that would require the department to set maximum contaminant levels for the chemicals and would also put in place an interim standard for contamination of 20 ppt. It was heard in committee on Thursday and held for further study. (A separate bill is also under consideration in the legislature to prohibit the substances in food packaging.)

“This is a public-health emergency, and we need states to take action now,” said Amy Moses, director of the Conservation Law Foundation in Rhode Island.

Swallow says that the state is working hard to look for PFAS contamination. She emphasizes that four out of every five samples from Rhode Island drinking water supplies have detected none of the chemicals and, when the compounds have been found, the levels are nowhere near those reported in Vermont, New Hampshire and other states.

That doesn’t mean that Rhode Island won’t reconsider its stance once the current round of testing is completed, she added. But she believes that the state is in a position to take what she described as a more deliberative approach.

“Given the occurrence data that we have so far, we feel like we have the time to be science-driven,” she said.

The highest concentrations of PFASs found in Rhode Island so far are in the groundwater around Naval Station Newport, where there used to be dedicated firefighting facilities.

The levels there are around 20,000 ppt. But the contamination is not considered a threat because Aquidneck Island is supplied with drinking water from reservoirs that aren’t near the base.

Levels are also high in Buckeye Brook in Warwick, which flows past T.F. Green Airport before emptying into Narragansett Bay.

Lohmann and his colleagues at URI’s Sources, Transport, Exposure & Effects of PFASs, or STEEP, center have found higher-than-expected levels of the chemicals in upper Narragansett Bay, too. The levels are well below what the EPA considers unsafe, but they are well above those in the Hudson River and other regional water bodies. The researchers believe the contaminants could be tied to the metal-plating or textile industries. Lohmann said the causes of the levels are of interest to scientists, but the concentrations shouldn't concern swimmers, fishermen or other users of the Bay.

The center, a partnership with Harvard University and the Silent Spring Institute, was created two years ago after advances in liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry improved scientists’ ability to measure the levels of PFASs in the environment. Its work is primarily focused on developing low-cost detection tools that could be used to collect ground, air and water samples, said Lohmann, an environmental chemist.

He believes the only effective way to control the release of PFASs in the environment is to cut down on their use and production. There are good uses for the chemicals — such as on coatings on heart valves — but there are safer alternatives in most instances, he argues.

“If it’s not essential, there’s no excuse to keep using it,” said Lohmann, whose past research focused on pollutants that include PCBs and dioxins.

Like those chemicals, which were banned as a class in the 1970s, many experts say that PFASs must be regulated as an entire family. Stopping the use of one variation doesn’t do much if another pops up in its place, they say. Moses compares it to a game of “Whac-a-Mole.”

Gray, of the DEM, a chemical engineer, agrees.

“Until these things are regulated as a class, it’s going to be almost impossible to keep up in a regulatory context,” he said. “That’s not just a Rhode Island problem. That’s a problem for everyone.”

On Friday morning, local, state and federal officials gathered in a dusty parking lot in Oakland to celebrate construction of the new water line from Harrisville.

Work had started weeks ago, but this was the official groundbreaking ceremony, attended by, among others, Jeffrey R. Diehl, CEO of the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank, which is financing the project, and the acting deputy director of the EPA’s water division in New England.

The $2.85 million needed to complete the new line is coming entirely from federal dollars funneled to the Infrastructure Bank through the EPA.

In an interview, Jane Downing, the EPA official, defended the agency’s response to the PFAS problem. Regulators are moving to take action as they understand more about the chemicals, she said.

“We have to just consider the science and understand that science will evolve and we’ll have more and more compounds to look for and at lower and lower levels,” she said.

During the ceremony, Nolan, of the Oakland Association, thanked all the parties involved for finding a new source of water for the village. But state Rep. David Place, a Burrillville Republican, expressed frustration at the amount of time it took.

“Two years,” he said. “There are going to be people that for two years have not been able to drink the water from their faucets by the time this is over and done with.”

— akuffner@ providencejournal.com, (401) 277-7457

On Twitter: @KuffnerAlex