Doctors say school mask mandate is a good move

With schools opening and the delta variant surging, here are five reasons physicians back Wolf’s order.

By Jason Laughlin STAFF WRITER

Pennsylvania’s school mask mandate is designed to limit COVID-19’s spread this fall, doctors and other health experts said, but much depends on how well people follow the rules. And no matter what, cases are still likely to surge in the coming months — the challenge is to keep the surge small to save lives and keep kids in school.

“I think masking is a part of it, but what we’re going to see is this experiment play out where different school systems are going to be impacted to different degrees depending on what mitigation strategies they’re going to incorporate,” said Craig Shapiro, pediatric infectious disease specialist at Wilmington’s Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children. “As cases increase there’s always going to be more spread within the school system.”

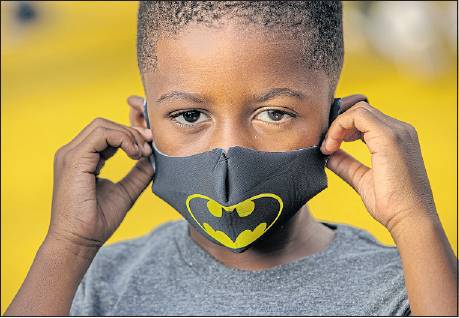

Gov. Tom Wolf declared Tuesday that masks must be worn in all public and private schools and child care centers, the same day the state reported a 277% rise in COVID-19 cases among children age 17 and un-See MASKS on A7

Continued from A1 der from mid-July to August. Just days into the school year, 5,000 students have tested positive for COVID-19.

While the delta variant doesn’t seem to affect children more seriously than other iterations of the coronavirus, said David Rubin, director of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Policy-Lab, it spreads more rapidly. And that means the rare serious cases among children — on the entire East Coast just 50 to 60 children are currently hospitalized for COVID-19, he said — will be more numerous. Other, less vaccinated parts of the country are seeing much higher rates of pediatric hospitalizations.

“I still think we’re better prepared in our region,” he said, “but it’s going to be a difficult early fall here, and I think people need to be a little bit cautious.”

1. Masks will help keep schools open

Masks and vaccinations are just two tools that will help schools from closing. Both will play important roles in preventing, for instance, a single COVID-19 case leading to quarantines that could keep students and teachers out of the classroom for weeks. Keeping schools safe will require other tools as well, including good ventilation and COVID-19 testing.

The CDC recommends quarantine for any unvaccinated person exposed to someone with COVID-19 — unless the infected person and the people exposed are all wearing masks and are children up to grade 12.

Schools closing again and shifting to remote learning, as they did in 2020, would be a worst-case scenario, Rubin said.

“The most important thing is that ... we’re trying to get kids back in school, allow them to have all the activities,” he said. “Kids were asked to shoulder a lot of the burden last year.”

Remote learning has been hard on kids. Students have performed worse this year on national assessments than in previous years, and the declines are even greater among many students of color and those from lower-income families. Inactivity and isolation have taken a toll on many children’s physical, emotional, and mental health.

2. Masks in schools also protect parents, families, and staff

The delta variant being more transmissible also means infected children could be more likely to pass it along to family members.

So even though children are far less likely to be hospitalized with COVID — delta or any other variant — they likely can spread it as well as anybody can.

“There’s no biological reason to believe children are less likely to transmit this virus than adults,” said Michael LeVasseur, a Drexel University epidemiologist.

Schools that have opened with no masking rules have already shown the value of face covering.

“In the South and Midwest, some school districts that have opened that haven’t incorporated these strategies have already seen significant impact to their student bodies and to their staff,” said Shapiro. “Vaccination of all those staff and students as well is enormously important.”

Of course, children under 12 are not yet eligible for vaccination, making masking even more essential.

“This is a disease spread by droplets and aerosol,” said Jeffrey Jahre, head of academic affairs and an infectious disease specialist at St. Luke’s Hospital and Health Network, which has 12 hospitals in the region. “If you have a proper covering you’re going to have less spread.”

3. Schools are safer when teens and adults are vaccinated

The best tool for keeping schools open is vaccinating all who are eligible, Rubin said. So far in the pandemic, children have tended to catch COVID-19 at home, and parents and older siblings being vaccinated greatly reduces the chance of that happening.

A Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia review of vaccination data found states with the lowest adult vaccination rates also had the highest rates of children hospitalized for COVID-19.

It remains unclear when children younger than 12 will be eligible for vaccination, but Rubin said that will be a pivotal moment to revisit masking policies.

“Once everyone’s been offered vaccinations you can’t continue to craft policy around those who have not been vaccinated,” he said.

4. Hospitals are already packed

Though pediatric hospitalizations for COVID locally are low, it’s important to remember that COVID isn’t the only reason kids need serious medical care.

“The children’s hospitals are basically full. Some of them have had to fly kids out to other hospitals, to hospitals that have beds available,” Shapiro said. “If there are a number of viruses circulating, flu and other respiratory viruses circulating at the same time as there are cases of COVID rising, that could be a recipe for disaster.”

Children’s hospitals and facilities with pediatric wards are seeing a glut of young patients. Respiratory viruses more common during the fall have surged this summer as families left their pandemic isolation.

Those illnesses can be serious for the very young children who in lockdown didn’t encounter the usual viruses.

“They have ... never had a fever, never had a cold, never had an infection,” said Jennifer Janco, head of pediatrics at St. Luke’s University Health Network, a regional system of 12 hospitals. “It maybe makes it a little bit different because they’ve never had them before.”

Health conditions that families put off dealing with during the worst of the pandemic are being addressed. Perhaps chief among them: Children’s behavioral health needs have soared, Rubin said, likely aggravated by the stress and isolation of the pandemic.

5. Masking now means we can unmask sooner

Now — as the weather cools, people move indoors, and viruses of all kinds thrive — is the best time to put on a mask, Rubin said.

“I think we have to prepare that transmission is going to peak for a bit,” he said. “It’s more likely to occur in the first two months of school than waiting until November and December.”

Depending on vaccination rates, case counts, and transmission rates, he said, schools might be able to make masking policies more lenient later in the year. But with so much at risk, now is not that time.

“That is the moment of time we’re in,” he said, “a tenuous moment where we’re trying to find out how to accommodate our lives.”

^215-854-4587

"jasmlaughlin