PART 1 OF A SERIES

Judges Rule

When it comes to probation, Pennsylvania has left judges unchecked to impose wildly different versions of justice.

By SAMANTHA MELAMED and DYLAN PURCELL | STAFF WRITERS

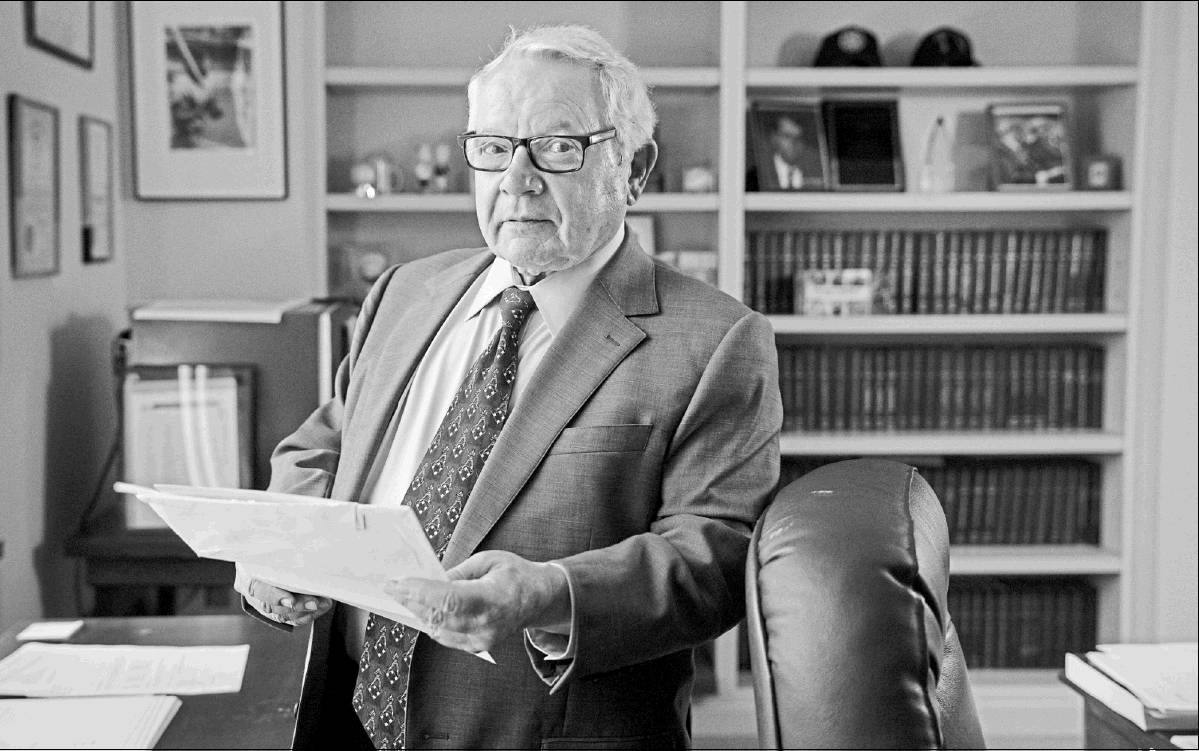

It’s 11:30 a.m. when Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Rayford Means barrels into his courtroom to address his 8 a.m. docket, and the courtroom is filled to capacity — people dressed in ripped jeans and sweatshirts squeezed onto the benches and standing uneasily by the door.

Almost all of them are here for probation-violation hearings, and Means kicks his courtroom into motion with an energy that’s more ringmaster than judge, instructing staff to call cases in a fashion that will allow him to toggle efficiently between those waiting in the courtroom and those who need to be brought up from the basement holding cells in the Stout Center for Criminal Justice.

“We’re gonna go back and forth: bail, jail, bail, jail,” he says. “I need a body in that seat.”

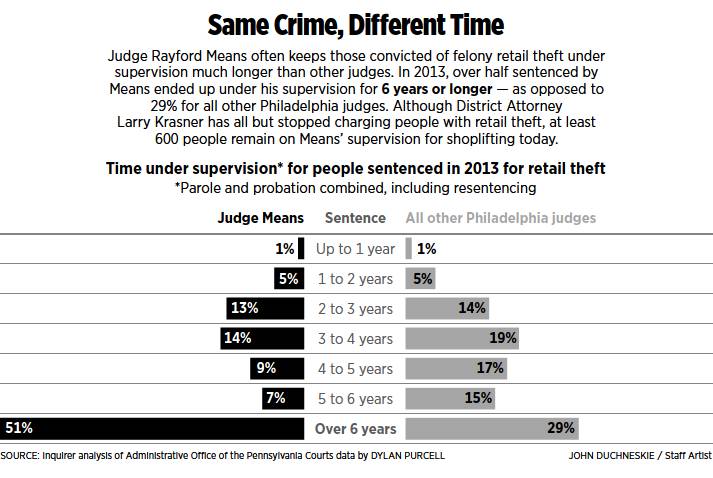

There are more people tethered to Means — and for longer stretches — than to any other judge in the region. He has imposed probation more than 13,000 times since 2012, and given out more five-year probations, more 10-year probations, more 15-year probations than any other judge. And when people violate his conditions of probation or commit new crimes, they all end up right back in this courtroom.

“You ever seen the movie Old Yeller? I’m like Old Yeller. I’ll be here,” he told one man. “You know Michael Jordan? You know how they used to say all championships come through Chicago? You gotta come here through me.”

As a result, being on his probation can feel like a life sentence, as ever-extending probation terms carry his regulars from late teens to young adulthood to middle age.

In court, he recommends treatment for some, urges others to apply for Social Security Disability, advises almost everyone to marry (for financial reasons, if nothing else), and even offers to officiate the weddings.

On a Tuesday in April, a couple took him up on it. The vows took place right in the middle of a hearing for Luis Rivera, 31, who was on probation for six different drug convictions and faced a new and very serious charge, aggravated assault. First, Means heard Rivera’s request for the judge to lift his detainer. Then, he conducted a brief ceremony (the bride wore a turquoise T-shirt and studded jeans; the groom, a white button-down a public defender had fished out of a closet somewhere in the courthouse). Finally, Means agreed to remove the detainer, ensuring a house-arrest honeymoon.

Kassandra Cruz, 25, left the courtroom glowing, orbited by two giggling children in Hulk and Spider-Man masks. It wasn’t her dream wedding, she admitted, but Rivera had liked the idea. “That’s what he wanted. He’s been his judge for so long,” she said. To her, probation is “a process. It can break you. You have to be strong and be supportive. What we do is we pray.”

How one judge can have hundreds of people tied to his probation for decades on end comes down to Pennsylvania’s unusual laws. Whereas many states cap probation at just three to five years, Pennsylvania is one of just eight states where probation can last up to the maximum sentence for an offense.

And, in Pennsylvania, probation violations carry unusually weighty consequences.

If a person is released from prison on early parole and then commits a violation, the worst that can happen is he has to serve his “back time,” or the unserved portion of his original sentence.

But if that person is also sentenced to probation, a term of community supervision much like parole, he’s in a far more tenuous position. In response to any violation, a judge could sentence him to up to the maximum term allowed for the original offense — which would be far longer than any jail time a judge might typically impose to begin with. In the case of some drugdealing charges, for instance, that could be up to 15 years in state prison.

Moreover, while Pennsylvania was one of the first states in the country to institute sentencing guidelines — and has achieved 90% compliance with them — the guidelines are silent on how to impose probation. And, there are no guidelines at all for how to resentence those found in violation of probation. In such cases, judges have an array of options, ranging from permitting probation to continue, to imposing a new term of probation, to sentencing a violator to county jail or state prison — limited only by that maximum sentence.

The state legislature tasked the Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing with creating resentencing guidelines a decade ago, but the commission got around to producing a draft version only this spring.

For now, judges continue to impose their own ideas of justice.

“There are many judges who feel they have the discretion to revoke probation or parole whenever they feel that it seems to be working inadequately as far as reforming the person or rehabilitating the person,” said Leonard Sosnov, a Philadelphia public defender. “That kind of standard is vague and, given its incredible vagueness, is subject to real arbitrariness in how it’s enforced.”

He recently represented Darnell Foster, a 22-year-old whose probation was revoked for posting images to Instagram depicting guns and drugs. Foster said he was merely presenting a front; he’d found the photos (including one, memorably, spelling out “F— you” in Percocets) on the internet and reposted them. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled in August that the court had wrongly revoked Foster’s probation, given that he had not violated a stated condition of supervision.

Means, like other judges, faces an array of competing motivations, one being perceived pressure to efficiently dispose of cases. (He even posts lists on his wall of the cases disposed each day to document his progress.)

Revoking probation and resentencing is one way to attain a disposition — far more quickly than, for example, scheduling another status hearing to see if a person in violation can get back into compliance. Another way is to encourage a guilty plea. Most efficient of all is when a defendant who is already on Means’ probation — but is now facing a new criminal charge that constitutes a potential probation violation — consolidates all his cases before Means, so that the judge can resolve the new case and the violations in one sitting.

“ There are many judges who feel they have the discretion to revoke probation or parole whenever they feel that it seems to be working inadequately as far as reforming the person or rehabilitating the person. That kind of standard is vague and … is subject to real arbitrariness in how it’s enforced.

Leonard Sosnov, Defender Association of Philadelphia

To get the new case moved to Means’ courtroom, the defendant will have to agree to plead guilty and request consolidation — a move Means openly encourages.

Recently, he told lawyers to send a protracted case out of his courtroom. “I’m not concerned about a single. I’ll hold a five, a four, a trey, a deuce,” he said, referring to defendants on probation for five, four, three, or two different cases at once.

“I’ll never let Rhonda go,” he said of a woman whom he has sentenced on 20 different cases, dating back as far as 1995, almost to the start of Means’ career as a judge. She has violated probation repeatedly — on one occasion being sentenced or resentenced on a notable eight retail-theft cases at once — and is currently scheduled to remain under Means’ supervision through 2025.

In one-third of the sentences he has imposed since 2012, he was addressing two or more cases at once; roughly 12% were for three or more cases.

In court, Means has lectured defendants on the benefits of consolidating their cases and taking a plea deal in his courtroom. “You take this to trial,” he told a 28-year-old man facing aggravated-assault charges on top of a violation-of-probation for a robbery, “your kids are graduated from high school, they got married and had children. You take the deal, you’re out when your kids are 4, 9, and 10.”

Another man on probation, Ronnie Tillman, declined to consolidate his cases before Means, instead going to trial in a different courtroom for a burglary. He was convicted, and sentenced to a 4-to-8-year prison term.

Back in Means’ courtroom for his probation-violation hearing, Tillman ventured an explanation. “I was doing good —” he began, before the judge cut him off in a moment of pique. “You were doing good until you were charged with committing a burglary, and went to trial and were convicted. Anything else you want to say?”

Tillman declined, and Means lodged his sentence: an additional 8 to 16 years in state prison.

Later, though, a public defender would file a motion to reconsider, and Means would relent, choosing not to extend Tillman’s prison time at all.

In many of the consolidated cases, Means’ sentences ultimately reflect remarkable leniency for individuals many other judges would have sent to state prison.

The lawyers in his courtroom sometimes appeal to his compassion for bumblers, like Marcus Quinones, who was high on K2 when he tried to hold up a convenience store with a pen and ended up getting shot by the clerk, four times.

A woman nearby, waiting for a SEPTA bus, was also hit with a stray bullet.

“He’s violated nearly every period of supervision, 15 times. … I don’t think he’s amenable to supervision on the street,” the prosecutor said, noting Quinones was already serving eight years’ probation for two other crimes. The guidelines, he told the judge, called for four or five years in prison.

Means gave Quinones time served in jail and yet more probation.

Means says his focus is rehabilitation. “One of my theories is that you can make a person more of a hardened criminal [by sending them to prison],” he said in an interview. That’s why he prefers probation, where he can give people a list of employers, encourage them to get a GED, to marry, to engage in pro-social activities.

His courtroom is filled with people coming from broken families, he said; his is, quite literally, an approach guided by paternalism. “I try to patch up the holes of what society has lost.”

“I can give that person a chance,” he said. “If you see longer periods of probation with me, it’s because I’m giving the person the opportunity to be reformed. But if you go out and commit a crime, I can reach out and get you.”

‘To vindicate the authority of the court’

Wander the floors of the Stout Center for Criminal Justice in Philadelphia, and it becomes clear that, depending on the courtroom, being on probation can mean something wildly different.

Some, like Means’, are filled to overflowing, with case lists five or six pages long tacked to the walls and those in violation filing in to be resentenced, then pouring back out onto the street. In others, the defendants are more likely to be walked into the room in shackles — then ushered back out under the weight of a new jail or prison sentence.

Defense lawyer Francis McCloskey said that when he negotiates for clients, he sometimes encourages them to accept prison time rather than pushing for probation. “It’s going to depend on a number of factors. It depends on your client; it depends on what they’re on probation for,” he said. “The biggest one is: Whose supervision are you going to be on?”

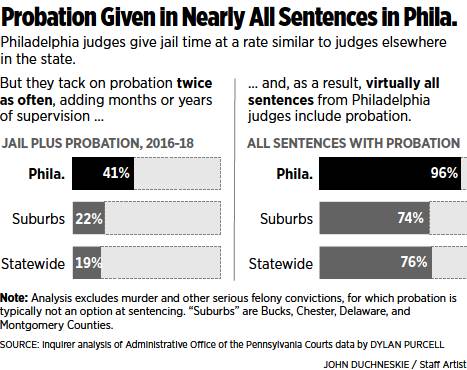

A review of 13,500 recent cases in Philadelphia shows 75% of violations occurred within the first two years and 90% fell within three years of the initial sentence. Recognizing that extended supervision offers diminishing returns — and could actually set people up to fail, by prolonging surveillance and continuing barriers to stabilizing employment, education, and housing — Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner announced this spring that his office would avoid seeking probation or parole terms in excess of three years whenever possible.

Yet, many judges continue to impose supervision terms longer than that. Statewide, the average probation term is three years. About 10% of probations are five years or longer; some run 10 or even 20 years.

In certain courtrooms, those numbers are far higher. Means gives out around a thousand fiveyear probations in an average year, to nearly one-third of those he sentences. Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Gwendolyn Bright imposes such lengthy terms at a higher rate. She deems 40% of her cases to require probations of five years or longer.

One woman, in her early 30s, had been on Bright’s probation for theft since 2009. Though she hasn’t been convicted of another crime in the last decade, she was back in court this July for a violation hearing related to spotty attendance at her probation appointments, a positive marijuana screen last fall, and her failure to complete a GED program Bright had ordered. In court, her probation officer acknowledged that the woman, a single mother, was straining under the obligations of two jobs and three children, who had school and legal issues of their own.

Bright was unmoved. “This is like a walk in the park. … Exactly what is it that is so overwhelming?” she asked. Complaining that the probation officer was “awfully nonchalant” about the violation, Bright ordered the agent replaced with someone who would hold the woman’s “feet to the fire.”

Pennsylvania law sets limits on imprisoning people for probation violations. A judge may do so only if the person has committed a new crime, is “likely” to commit a crime, or if it is “essential to vindicate the authority of the court.”

Judicial interpretations of that law vary. For instance, when Means revokes probation, he sends violators to state prison only 3% of the time.

Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Anne Marie Coyle, on the other hand, sent about half the people whose probation she revoked from 2013 to 2018 to state prison — the highest rate of any judge in the city, though the overall number of cases she handles is lower than Means. That group includes some people convicted of low-level crimes like drug possession and shoplifting, who face years in prison for violations even though they have not committed new crimes.

Among them was Aaron Lucky, who was on Coyle’s probation for a 2013 crime — stealing body wash from a Philadelphia drugstore. Three years later, he failed a drug test and missed several appointments with his probation officer. He told the judge he missed the appointments because he’d been working full time, and submitted a letter from his employer.

Coyle cited Lucky’s lengthy, though nonviolent, criminal history and imposed the maximum legal sentence for the violations: 3½ to seven years in state prison, a term Pennsylvania’s guidelines indicate for crimes including voluntary manslaughter, rape, or aggravated assault. She added that she would recommend to the state parole board that Lucky serve the entire seven years. When Lucky appealed, the case came back to Coyle, who affirmed her own sentence.

“ I try to patch up the holes of what society has lost. … If you see longer periods of probation with me, it’s because I’m giving the person the opportunity to be reformed. But if you go out and commit a crime, I can reach out and get you.

Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Rayford Means

Coyle said it would not be appropriate to participate in an interview, but from the bench she called The Inquirer’s finding that she sends probation violators to state prison at the highest rate of any judge in the city “interesting.” Coyle said that rate may reflect the seriousness of cases that flow through her courtroom, a designated “major trials room.”

Better known these days than Coyle is Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Genece Brinkley, whose repeated reincarceration of the rapper Meek Mill, for 2007 drug and gun charges, helped propel the issue of probation reform into the national spotlight. The case of the 33-yearold rapper, who spent more than a decade on probation, shocked the public after Brinkley sentenced him to two to four years in state prison reportedly for a record of violations including scheduling out-of-town concerts without permission; two arrests (for reckless driving and for fighting); and sorting clothes, rather than serving food, during court-mandated community service at Broad Street Ministry. After a legal battle, he was released on bail and flown by helicopter directly to a 76ers game — an episode that became the climax of an Amazon docuseries released this summer.

In a review of 576 cases that passed through Brinkley’s courtroom since 2012, she sentenced about one in seven to terms of confinement at least three times. And, she sent 39% of those whose probation she revoked to state prison.

Less fortunate than Mill is Nijha Green, who’s a year older than the rapper and has none of his wealth, famous friends, or high-powered lawyers. Just like Mill, he first appeared before Brinkley more than a decade ago, in 2005, when he was convicted on a drug charge — and sentenced to 11½ to 23 months in jail, plus three years’ probation. He was paroled to house arrest, and he rebelled: He cut off the monitor, went on the run, and picked up another drug-possession charge. “I was 19 years old,” he said recently. “I’m not gonna blame it on any other factors but my own impulsive behavior.”

Since then, though, he’s grown up — he’s raising his three children, and he’s learned to enjoy legitimate work, as a cook at restaurants near his home in Williamsport, in central Pennsylvania. Since 2006, he has not been charged with another crime.

Yet, Brinkley incarcerated him three more times for noncriminal violations. One was in 2010, after Green moved out of Philadelphia without permission. Green said he had no choice: He had a girlfriend and a small child to provide for, and they had nowhere to stay in the city. Brinkley sentenced him to 2½ to five years in state prison.

Green was released in 2012 and successfully completed state parole in 2015. “We are pleased to advise you that our records indicate you have completed your supervision, and you are hereby issued a final discharge,” read the letter from the state parole board, wishing him success in the future. He was free.

Then, in the middle of the night in 2017, the police came to his mother’s house in Philadelphia. “They were banging on my door, flashing lights in my house,” said Lisa Pettey. “I have never been arrested for any type of crime. It was scary!”

That, Green says, is when he learned he was supposed to report for county probation after the completion of his state parole. It’s a common mistake — but it made Green an “absconder.” Brinkley sentenced him to jail yet again — for up to 23 months, plus one more year of probation. She entered repeated orders denying his motions for parole, ensuring he’d remain in jail for nearly two more years. On each order, she wrote simply, “judicial discretion.”

At the city’s high-security jail, Green said, he was gripped by fear and anxiety, for the first time in his life seeking out antidepressants. He fretted all day long about his young children, aged 4 and 6, who live with his grandmother, and worries especially about his oldest, Jayla, who turned 12 this year.

“She doesn’t have her mom around at all, so with me being gone I think she feels alone — like we don’t really love her. She wrote me to say this is the second birthday I have missed in a row, and why ain’t I home yet?” he wrote in a letter from jail over the summer. “She just can’t see, if I didn’t do anything, then why was I locked up, and why so long? I think she thinks I’m lying and have gotten myself in big trouble.”

On Oct. 7, Green completed his 23 months in Philadelphia jail and was released. He spent hours circling back and forth between the different cashier desks at two different county jails, until finally someone unearthed his photo ID. He reported to the probation office, fretting that they wouldn’t let him return home to Williamsport, and his children.

His probation officer agreed to put in for the transfer, and he caught a ride upstate. It was a joyful reunion, but also a reminder of how much he’d missed. “They got so big,” Green said.

And now that he was out, he was in a bind yet again: Probation had approved him to live at his grandmother’s house pending the transfer, but because his grandmother was now also a respite foster care provider she couldn’t have him there while on probation.

“I just gave them this address,” Green said, stewing over the potential consequences, including his fear that his transfer to Williamsport wouldn’t go through. “I don’t want to turn around and give them a new address. I don’t want to give them any negative thoughts that I’m floating around or trying to manipulate the system.”

Different courtrooms, different rules

In the absence of rules or even guidelines on how to handle revocations, each judge must make up his or her own set of norms. Often, judges appear to be in triage mode, responding to each new emergency with the limited tools available to them: jail, state prison, court-ordered treatment, or ever more probation.

“We’re the city’s largest service provider,” said one judge, who declined to speak on the record.

Another Common Pleas Court judge, Frank Palumbo, often describes what he’s trying to do is get offenders’ “brains straightened out” — and to retain the leverage he needs to do so.

So, he looked with pity at a man who had been on probation for theft since 2011, found in violation and resentenced four times already when he washed up in Palumbo’s courtroom in July, accused of violating yet again. This time, he had tested positive for marijuana and he had a new conviction in Montgomery County, where he’d attempted to use a counterfeit $100 bill at a Wawa to buy a pack of cigarettes, a hot dog, and a Sprite. He served nearly 10 months in jail there — far longer than he would have faced in Philadelphia, the lawyers in the room remarked. Yet, by agreement, they proposed even more jail time for the probation violation: an additional three to six months.

“ She wrote me to say this is the second birthday I have missed in a row, and why ain’t I home yet? She just can’t see, if I didn’t do anything, then why was I locked up, and why so long? I think she thinks I’m lying and have gotten myself in big trouble.

Nijha Green, who was incarcerated almost two years for a probation violation, describing a letter from his daughter Jayla, now 12.

Palumbo rejected the deal.

“My heart says I can’t give him [more jail time] for being that stupid,” he said. Instead, he gave him four more years’ probation. Palumbo said he needed that time to get him on track. “This guy clearly should be on supervision. … Yes, probation in this case is not working. If I give up, I lose my assignment. People say we’re over-probating, we’re overincarcerating, and nothing seems to work. But I want to keep trying.”

In an effort to impose order in the courts — and on the chaotic lives streaming into the courtrooms — some judges spend their days trying to convince defendants that outcomes in their courtrooms are predictable.

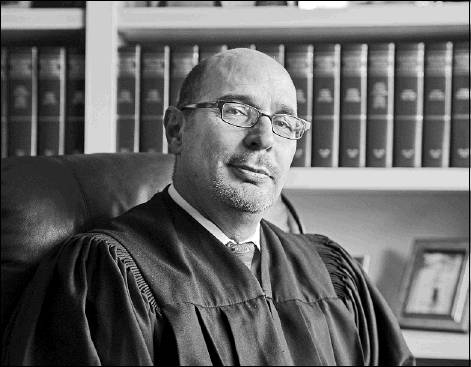

“I’m the worst judge to run from,” Judge Robert Coleman tells those on probation. “I take it very seriously.”

He gave such a warning to a man who was on probation for a 2016 assault when he made a calculated decision to stop reporting, in part because he was busy working and caring for his two young children. “I would’ve turned myself in, but my kids would have been alone,” he told the judge.

Coleman gave him four months in jail and another year on probation, adding, “Next time it will be six [months]. Do not run away from me.”

Judge Scott DiClaudio, meanwhile, has developed a special protocol for those convicted of gun charges: Their names go on a numbered list on a sheet of yellow legal paper, kept in a plastic sleeve on the bench. “Your number is 1,132,” he told one defendant, sentencing him to three years’ probation. “You’re not going to carry a gun while under my supervision, and if you do, I will give you 2½ to five years in state prison just for the violation. … Or, do what you’re supposed to do, and I’ll take a year off of your supervision.”

DiClaudio told him the system works: Only three people on the list have received that punishment. “Don’t be number four.”

Though the change may be difficult to detect, attitudes are evolving, according to Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Benjamin Lerner, who first came to the bench two decades ago.

“I think judges have learned … that we need to be more careful about not only the length of time we have someone under supervision, but the number and type of conditions that we impose. There’s been a growing realization about that for as long as there’s been a growing realization about the dangers of mass incarceration.”

As for judges who aren’t getting that message, he said, it’s up to the state Supreme Court or other court leaders to give guidance.

“To the extent that there may be real outliers, the management of this system is responsible for education, training, and correction,” he said.

Philadelphia’s court leadership declined repeated interview requests.

For now, the most immediate prospects for reform may come from Harrisburg. The state Commission on Sentencing held hearings this year on its first set of draft guidelines for probation revocations.

“We’re on the path to saying … if at the least you said to the judges, ‘Go back to the original guidelines and consider those,’ that might be a good first step,” said Mark Bergstrom, the commission’s executive director.

Legislation currently under consideration in Harrisburg would take that work further, setting limits on probation and capping punishments for violations that are not new criminal convictions.

In Philadelphia, District Attorney Krasner has opted not to wait for that law, instead instituting an officewide policy to seek limited terms of community supervision and to argue that such noncriminal violations should not result in more than 60 days in jail.

Krasner said recently that he’s seen success in attaining shorter supervision terms on new cases; according to an analysis by his office, the total amount of probation imposed is down 43% across all cases compared with before his tenure. “We’ve been less successful in taking the number of people on supervision and cutting it down,” he acknowledged. “Not every judge agrees with our policy.”

A lower standard of proof

When he was younger, Johnny Colon had a history with the law — an ugly rap sheet including charges of drugs, guns, robberies. But, he insisted, that was behind him. “I been working since 2015,” he said, at a catering company and a thrift store while he served out his probation. “I never turned back around.” Last year, he had just stopped by a house his wife owned, he said, when police showed up with a warrant for his nephew, who it turned out had been dealing drugs out of the house and had a cache of drugs and guns.

“They took a bundle pack out and threw it on my chest and said, ‘You’re going to jail, too,’ ” Colon said.

But his claim that police falsified evidence was not tested at a trial.

Before that could happen, the Philadelphia Common Pleas Court judge overseeing his probation, Anne Marie Coyle, held a separate hearing on the alleged probation violation.

Coyle is one of just a few Philadelphia judges who persist in holding probation-violation hearings for individuals who are charged with new crimes before those new cases are complete.

Known as a Daisey Kates hearing, after a woman who lost a 1973 state Supreme Court case challenging the practice, such a proceeding is perilous for a defendant like Colon. Whereas at trial he’d be innocent unless proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, a violation-of-probation finding requires only a “preponderance of evidence” — the slightest tilt toward guilty on the scales of justice. The rules of evidence are relaxed, too, allowing hearsay to be admitted. And lawyers typically avoid putting on much of a defense, since doing so could spoil their strategy for the upcoming trial.

At one recent such hearing in Coyle’s courtroom, the DA called a police officer to testify in the case of a young man who was stopped for violating probation, searched, and taken into custody. Only later, at the police station, did the officer’s partner — who wasn’t at court — notice the man “fidgeting” and find drugs on him. The defense lawyer never raised questions why the drugs weren’t found in the initial search, or what fidgeting had to do with it, or how they knew the drugs weren’t already in the back of the police car. Coyle found him in violation.

In 2018, DA Krasner announced his office would not request Daisey Kates hearings, citing the potential for appeals over perceived due-process violations and the strain on resources associated with prosecuting a crime twice. After Coyle controversially sought to appoint a special prosecutor to hold such a hearing, the DA began conducting them under protest.

Under Coyle’s court order, the DA conducted a Daisey Kates hearing on Colon’s drug charges, and Coyle found Colon in violation. Then, to Colon’s great relief, he beat the new case. A judge had already thrown out five of the six charges against him at his preliminary hearing, and the last charge, misdemeanor drug possession, was dismissed for failure to prosecute in advance of the 180-day “speedy trial” deadline.

Given that outcome, Colon was calm as he returned to Coyle’s courtroom to be sentenced on the probation violation. He believed he was going home.

“It is apparent to me that you constitute a danger to the community, and are most disrespectful of the supervision of probation and parole,” she told him. “You have thumbed your nose in the face of authority for a very long time, and it will end today.”

Coyle sentenced him to 5½ to 14 years in state prison.

Colon, hunched over the defense table, pressed his forehead into his hands. Later, he explained that he was trying to stay calm; he’d had a small heart attack when he was first arrested, attributed to the stress.

“I love you, Papito,” his mother, Carmen Cruz, called after him from the back of the courtroom, as a sheriff guided him back toward the holding cells. smelamed@inquirer.com

215-854-5053

@samanthamelamed dpurcell@inquirer.com

215-854-4915 @dylancpurcell

“ We need to be more careful about not only the length of time we have someone under supervision, but the number and type of conditions that we impose. There’s been a growing realization about that for as long as there’s been a growing realization about the dangers of mass incarceration.

Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Benjamin Lerner