New Dawn

The legacy of the Quinnipiac people endures in a soon-to-be-upgraded viewing space.

BY RANDALL BEACH

Two men dedicated to preserving and honoring the culture of the Quinnipiac people — one an eccentric Stony Creek-based collector of artifacts and the other a Guilford school teacher —have made it possible for us to learn about these Native Americans and see those historic items. As a result of their efforts, which have led to increased public interest in the Quinnipiacs, the Quinnipiac Dawnland Museum, kept in the loft of a barn at the Dudley Farm Museum in Guilford, will soon get a new, larger home at the farm.

The Stony Creeker who built the collection was Gordon Brainerd. He spent more than 40 years seeking out projectile points (arrowheads) and other Quinnipiac remnants in the woods, fields and beaches of Branford and adjoining towns. Brainerd, a beekeeper by trade who died last August, was never able to establish a bloodline connection to the Quinnipiacs. Nevertheless, he became known as Gordon “Fox Running” Brainerd. “Gordon was not a Quinnipiac,” says Jim Powers, the retired school teacher who now oversees the collection. “But I think he was Quinnipiac in his soul.

“He was incredibly dedicated to the idea of preserving the history of the Quinnipiacs,” Powers adds. “He scrounged around Branford, Madison, Guilford, North Haven, New Haven and West Haven. He wasn’t an archaeologist but did have an archaeologist’s eye. He was self-taught. He’d walk along the shoreline at low tide. He’d go to fields when they were first plowed and he knew the best places in the woods. People would also come to him and say, ‘Gordon, we’ve got some arrowheads in our backyard.’’’

Powers befriended Brainerd in the 1990s when the two men discovered they had a shared interest in the Quinnipiacs. “It was Gordon’s passion for their history that we at the Dudley Museum really hooked into.” Brainerd donated his collection to the museum in 2003.

Beth Payne, the Dudley Farm Museum’s director, says, “I’m pleased we’re able to do something that would have made Gordon so pleased, and that people are interested in the Quinnipiac collection and his life’s work.” She’s also “absolutely thrilled” that Powers is carrying on Brainerd’s mission. “Jim has the expertise as well as the enthusiasm. He’s on top of it and will make sure it’s done correctly.”

It’s been a “lifelong journey” for Powers. “As a kid playing in the woods, when my friends and I played cowboys and Indians, I had to be an Indian. I was drawn to it. I found their culture, the little I knew about it, fascinating.” Powers took courses in Native American culture at Wesleyan University, where he majored in European history. While at Wesleyan he became friends with Native American students. And when the student later became a teacher at Guilford High School, Powers created the course Local History Through Archaeology. He retired in 2017.

Powers then wrote Shadows Over Dawnland, a novel about a Quinnipiac youth whose life is upended by the arrival of English settlers. The Quinnipiacs called their region Dawnland because it was the first place where the dawn’s light appeared every morning. Powers notes the Quinnipiacs, like most native peoples, welcomed the Europeans. At their peak there were 2,000 to 3,000 Quinnipiac people, Powers estimates. They lived in villages in New Haven, Branford, North Haven and Guilford.

But the Europeans brought with them smallpox. The disease spread rapidly through the Quinnipiacs, who had no immunity to it. An epidemic in 1633–34 wiped out about 80 percent of the Quinnipiac population.

For thousands of years up until then, Powers notes, the Quinnipiacs had creatively adapted to changes in the environment, including climate change. “They had to be really attuned to their environment. We could learn from native people.”

Powers says we should also realize how long Indigenous people lived here: perhaps about 14,000 years, compared to just 400 years for European settlers and their descendants. “Many of us have lost a sense of place, a connection to where we live,” Powers says, “and who the people were that lived here thousands of years ago, and the impact they had. Honoring the legacy of Native American groups is important.”

Some people are starting to understand this. Quinnipiac University student Daniel Galvet is taking a course entitled Practicing Archaeology, which explores our relationship to the Quinnipiac people. “The average Quinnipiac student today does not think very much at all about the people the school is named after,” Galvet says in an email. “I have heard many students say they were not even aware that the name Quinnipiac refers to the Indigenous people of this area.”

Galvet is trying to find Quinnipiac descendants, as is Powers. “Gordon used to tell me ‘They’re hiding in plain sight,’ they merged with the general population. Those people are here. We’re hoping they come forward. We want to work with them to keep their legacy alive.”

During a November open house at the farm, one of the visitors to the loft was Shannon Zich of Granby. After seeing the Dawnland collection, she said: “I think it’s really cool. I like that it exists. So many important historical items are lost. Here you see the way people used to do things. And the artwork is beautiful.”

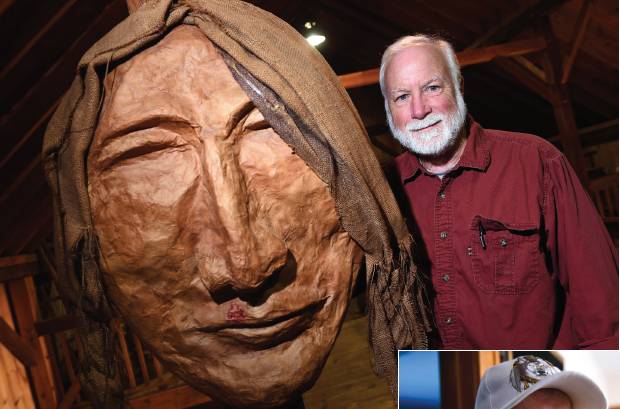

The tools and projectile points are supplemented by modern-day paintings of Native Americans. There is also a canoe made by Boy Scouts and a large papier-mâché head of a Quinnipiac man, created by middle school students. You can also see the ceremonial headdress Brainerd made and used when he “blessed” public gatherings.

One of Powers’ favorite parts of the collection is an array of projectile points Brainerd collected from different periods. “They reflect the evolution of the culture and technology based on the climate.”

In the future, visitors to the Dawnland collection will no longer have to navigate the staircase to the loft. The museum has received an anonymous gift of $50,000 to build a new structure nearby that will showcase the collection. Powers and Payne are optimistic construction will begin in the spring. They’re also planning to apply for a Connecticut Humanities grant to hire a consultant who would design the exhibits, adding visual aids.

Powers is encouraged by another sign of increased interest in the first residents of Connecticut: “Many people are coming forward who want to donate the artifacts they have found.”

Randall Beach is a former columnist and

reporter for the New Haven Register. He can be reached at rbeach8@yahoo.com.