A MILLION PLATES

A queer path to Vietnamese food & tradition

Collective brings together elders with trans and queer young adults in the kitchen

By Leena Trivedi-GrenierAs a kid in Saigon’s District 2, the floral, sweet smell of pandan cooking in coconut milk meant banh kep la dua (pandan waffles) to Trang Tran.

The sizzle of a street vendor pouring the batter onto hot cast iron would make Tran dance with happiness and hunger. That same perfume of pandan in coconut milk welcomed Tran’s family at the food court in Lion Plaza in San Jose after they immigrated to Hayward in 2002, when Tran was 10. Among the heady scent of nostalgia, Tran happily ate pandan waffles with a cousin.

To Tran, the waffle was a reminder of how Vietnamese culture could be preserved in a new home, and the power of food to connect generations. Tran, who is queer and genderqueer and uses they/them pronouns, struggled for years with growing apart from Vietnamese culture and experiencing rejection because of their identity. In 2016, those struggles inspired them to create QTViet Cafe Collective, which encourages reconnecting with Vietnamese foodways, storytelling, art and intergenerational community. When the group started hosting food pop-ups, Tran wanted food that had meaning to them, so they reinvented pandan waffles by serving them on a stick.

An important aspect of the group is healing from trauma. There’s intergenerational trauma from the Vietnam War, and many immigrants also experience a difficult separation from Vietnamese culture. There is also the rejection that many LGBTQ Vietnamese people experience within their own community. Tran says, “Growing up, I just felt like ... I can’t be Vietnamese and queer at the same time.”

Another inspiration for Tran to start the collective was a cooking class they attended in 2015 taught by Hai Võ. Võ, who is queer and doesn’t use pronouns, was teaching them banh tet, a sticky rice cake made for Tet, the Vietnamese New Year. Tran found it incredibly powerful to learn how to make this essential Tet dish in community with other queer people. “Just to know that this is how you fold the banana leaf, this is how you tie it to keep the water out, it was so profound and healing to me,” Tran says.

Võ became the second workerowner of the collective. As the group planned its first Tet celebration in 2017, it wanted to tap into the communal aspect of cooking for the holiday. Võ suggested having their elders teach queer and trans members to cook a meaningful dish from their lives in their own kitchens.

“The kitchen is a very central place for Vietnamese people,” Võ says. “Can we meet our families in their homes ... and show up as our full queer selves?” The “cook hubs” promote healing, Võ says, by passing down food traditions while giving the elders and queer and trans young adults a chance to share stories and break down stereotypes on both sides.

That first year, they asked parents of members to host cook hubs. Tran’s parents taught them how to make egg rolls, and a friend’s mom from central Vietnam taught them banh bot loc, tapioca dumplings with shrimp and pork. Tran works with elders in their day job as an organizer at the Oakland community organization Asian Refugees United, and one of the elders taught them how to make fried chicken. “For us to be in that space together, subtly but also very visibly queering up the kitchen with our elders ... it was really magical,” Tran says.

“Queer up” (bong len in Vietnamese) is a phrase the group uses often. To Tran, it means “an experience of being our full self and reclaiming a space that holds many traditional gender norms and roles ... we are building new ways of being with each other.” Võ adds that “bong” also means to brighten or sparkle — “it is that extra oomph of magic that we have when we’re in our fullest selves.”

QTViet Cafe member Jessie Nguyen, who uses they/them pronouns, has always had a close working relationship with their mother, Kim. In 2014, the two created Bicycle Banh Mi, a bicycle-delivery banh mi business in San Francisco. That grew into Little Window, a Vietnameseinspired catering service and pickup window in the Embarcadero. But even though their mom knew they were queer, she never talked about it.

“Mom didn’t grow up being around queer community, so she didn’t understand what it meant,” Nguyen says.

Nguyen introduced their mom to the group by asking her to host a cook hub for the 2019 Tet celebration, where she taught members canh kho qua, a pork-stuffed bittermelon soup in a pork bone broth. “Kho qua” translates to “hardships passed,” and it’s eaten at Tet as a reminder of life’s bitterness.

Nguyen’s mom enjoyed spending time with queer Vietnamese people in the group, and afterward, the two talked about queer identity, which brought them closer. Today, she comfortably uses the word queer, which Nguyen says makes them feel seen. Last year, their mom gave them her old ao dai (a traditional Vietnamese outfit) to wear to the Intergenerational Feast. “I paired the tunic with black leather pants! My mom described the outfit as very ‘bong,’ which means queer,” Nguyen says.

Võ grew up in a Catholic family, and coming out as queer and gay at age 23 meant many years of struggling for acceptance from Võ’s family. But after meeting Tran, Võ realized that family needed to be part of the healing process. Võ moved in to help take care of Võ’s mom, and the two cooked, shared stories and grew closer.

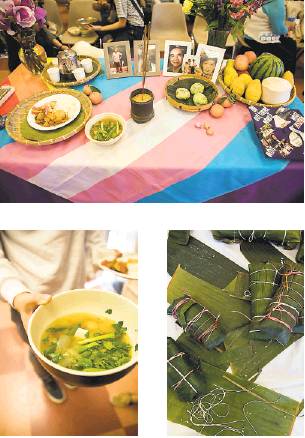

She passed in 2018, and for the 2019 Tet celebration, Võ placed her photo on the collective’s altar, which is an important Tet tradition. The altar is traditionally decorated with flowers, red fruit to represent love and food cooked by the family to welcome relatives to the celebration. “I had never seen an altar in a queer and trans space,” Võ says.

Võ’s father attended the event for the first time, where he sang with other elders and donated money to the group. Another part of healing, Võ tells me, is having elders meet other elders with queer or trans Vietnamese children. “I have never experienced my parents supporting something so close to me,” Võ says.

For their part, Tran also found acceptance from their parents after a performance they gave at one of the collective’s events.

This year’s Tet celebration, held Feb. 8 at San Jose’s Vietnamese American Community Center, featured one large banh tet cook hub. Attendees were surrounded by pounds of soaked Koda Farms sweet rice, containers filled with mung bean, sweet yam and taro fillings, stacks of vibrant green banana leaves and piles of string. The elders showed the young adults how to layer rice and filling onto banana leaves, and to fold and tie each package to look like a tied roast from the butcher.

Meanwhile, some of the elders shared stories in Vietnamese, with Tran translating. The mood was celebratory, and there was a powerful feeling in being in a space that honors Vietnamese culture and food traditions while uplifting queer and trans voices. It was Tran’s vision come to life.

With the connection between food and Vietnamese culture so undeniable, Tran hopes to host more intergenerational cook hubs in 2020. As the event’s emcee, Tracy Nguyen, reminded attendees, the way Vietnamese people say I love you is: “Con an com chua?” Have you eaten yet?

Leena Trivedi-Grenier is a freelance writer living in the Bay Area. Email: food@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @Leena_Eats

“The kitchen is a very central place for Vietnamese people. Can we meet our families in their homes ... and show up as our full queer selves?”

Hai Võ, QTViet Cafe Collective

This is A Million Plates, the Chronicle’s regular column about immigrant food in the Bay Area, centered around the theory that there are a million different plates of food eaten every day in this region.