SAN ANTONIO CLIMATE IN THE FUTURE

SIXTY DAYS A YEAR ABOVE 100°

Climate change debates aside, the raw numbers show San Antonio is becoming much hotter, much more often. What does this mean to our city, and to a state where nearly 40 percent of the labor force is working outside?

By Brendan Gibbons STAFF WRITER

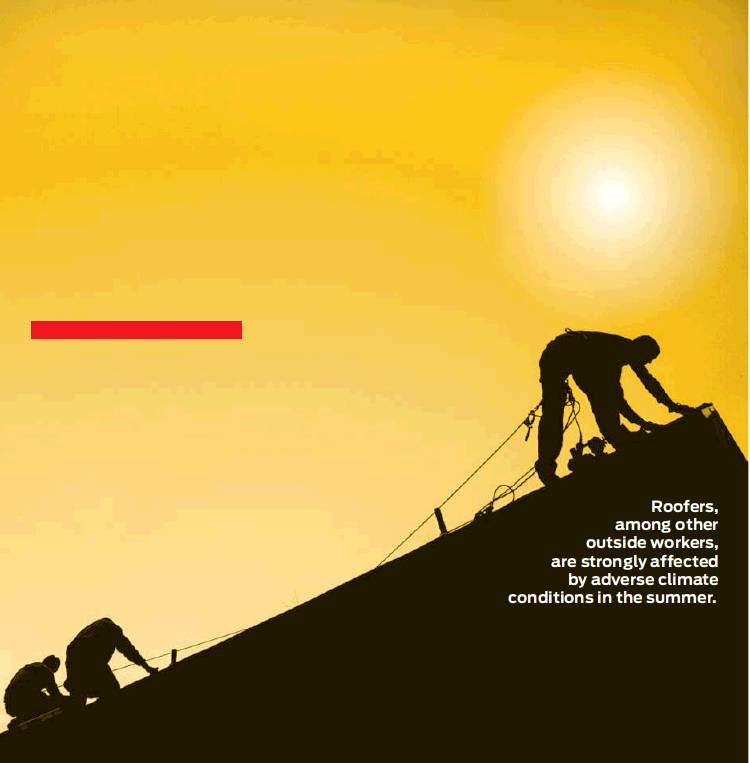

The intense heat of a July afternoon in San Antonio hit the crew of roofers from two directions.

As the air temperature reached 101 degrees, heat radiated down from the cloudless sky and shimmered up from the layer of white plastic the roughly 20 workers were sealing over black asphalt.

Despite their wide-brimmed hard hats, long sleeves, neck coverings and sunglasses, the workers needed shade and water breaks every 10 to 15 minutes.

“You definitely give them a lot of respect,” said project manager Jacob Aguirre, who manages three roofing crews for Beldon Roofing Co. “Somebody’s got to do it. Every building needs it.”

The roofing crew sweated through 15 days this summer when high temperatures reached 100 degrees or higher during what was a typical summer in San Antonio. Most people don’t realize it wasn’t always this hot here. When record-keeping in San Antonio started in the late 1800s, it took at least three or four years to rack up that many triple-digit days.

As the Earth continues to warm at a higher-than-normal rate in part because of burning of fossil fuels, climate scientists predict San Antonio will get even hotter. The city could see two to three additional weeks a year when temperatures top 100 degrees.

This warming will have consequences, especially to the local economy. Extreme heat will hit outdoor workers, the poor and the elderly hardest. For the better-off, climate change may not make San Antonio unlivable, but it will undoubtedly make life hotter and harder by the middle of the 21st century.

One prominent study published in the journal Science in June put Bexar County on the front lines of declines in the outdoor labor force, more heat-related deaths and a decrease in economic output.

The once and future heat

As the widest state in the continental U.S., Texas straddles the wet Southeast and the dry Southwest. It’s affected by many of the forces that shape the nation’s weather — arctic fronts, El Niño, west winds, Gulf air, tropical storms, the jet stream and the Bermuda High pressure zone.

“We’re at a clash between air masses,” University of the Incarnate Word meteorology Assistant Professor Gerald Mulvey said. “There’s juicy, warm air coming in from the Gulf. It meets this cold, dry air coming down from the Front Range of the Rockies.”

These conditions can deliver some extreme weather, especially San Antonio’s notorious swings between droughts and floods. One trend cuts through the noise, however: San Antonio is getting hotter.

Since reliable records began around 1880s, San Antonio’s average temperatures have climbed about 0.2 degrees Fahrenheit per decade for a total of 2.4 degrees, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. From 1961 to 1990, that warming accelerated, with a 0.7-degree-per-decade rise in average winter temperatures and a 0.5-degree increase in the summer.

The city also has seen more scorching hot days. In the past three decades, San Antonio has experienced an average 16 days per year of triple-digit weather.

The city’s three hottest summers have occurred in the past eight years — 2009, 2011 and 2013, with 59 days, 57 days and 41 days at or above 100 degrees, respectively.

In the 2010s, with 2 1/2 summers left to go in the decade, the city already has had 174 days at or above 100 degrees. That’s more than any decade in history.

The city was much cooler a century ago. From 1890 to 1899, San Antonio recorded only 39 days of 100 degrees or higher. By the 1950s, that had climbed to 125 days over 10 years.

After a dip to only seven days of above 100 degrees in the 1970s, a relatively cool decade, the mercury began routinely rising again. There were 102 days in the 1980s, 144 days in the 1990s and 148 days in the 2000s.

Multiple climate models show that by the second half of this century, San Antonio will experience more intensely hot days and fewer freezing days than any time in recent memory.

That’s according to computer modeling by scientists from universities and federal agencies like NASA and NOAA.

“They’re based on the laws of physics,” said University of Texas Professor Kerry Cook, who has worked with these models first-hand. At their core, the models simply apply Newton’s laws of motion and laws of thermodynamics to observed weather data, she said.

To get a future climate prediction, scientists set a geographic boundary and wait for weeks, sometimes months, for the model to deliver predicted outcomes, Cook said.

Some of the most precise climate data available come from the Third National Climate Assessment in 2014. The main model used in that study split the continental U.S. into a giant grid, with each rectangle taking up about 74 square miles. It then simulated the climate for each squares into the future.

Using this model, climate scientists predict in the years 2070 through 2099, San Antonio’s average annual temperatures will have increased between 4 and 8 degrees, according to a 2015 report by Texas Tech University Professor Katharine Hayhoe, who helped develop the model. Global warming beyond the 21st century will depend on how the world addresses fossil fuels.

That kind of temperature shift means 15 to 22 more days per year by mid-century when the daily high tops 100 degrees, Hayhoe wrote.

Cook also helped develop a different kind of climate model, which can be used to make more detailed predictions for a particular region. Despite their differences, the two models have similar projections about the future climate of Austin, which can also apply to San Antonio.

By 2040 to 2060, nearly every July and August will have on average 25 to 30 days when temperatures reach 100 degrees, according to Cook’s model output. Over the past decade, the average July and August have had between five and six and between 11 and 12 triple-digit days, respectively.

Compared to the National Climate Assessment model, Cook’s model predicts a more moderate rise in average annual temperatures — between 2.5 and 2.75 degrees Fahrenheit, with most of the warming occurring in summer and fall.

Feeling the heat

People who make their living outdoors are feeling these hotter days, degree by degree.

In the San Antonio-New Braunfels area, 63,900 people were employed in construction, mining and logging jobs in August, the latest numbers from the Texas Workforce Commission. The area also was home to 280 farm, nursery and greenhouse workers at that time, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As temperatures continue to rise, hot weather will take a toll on local economic output, according to the study published in Science that attempted to model the economic effects of climate change on every U.S. county.

By 2080 through 2099, Bexar County will see a 9.7 percent annual reduction in county gross domestic product compared to the 2012 output, the study states.

“Almost 40 percent of the Texas labor force is outdoor labor,” said James Rising, one of the report’s authors. They combined two dozen economic models developed by other researchers. “It’s high-risk for impacts from heat,” he said.

In Bexar County, Rising and his colleagues predicted a 2.5 percent drop in the available outdoor labor force, people like Ramiro Hernandez.

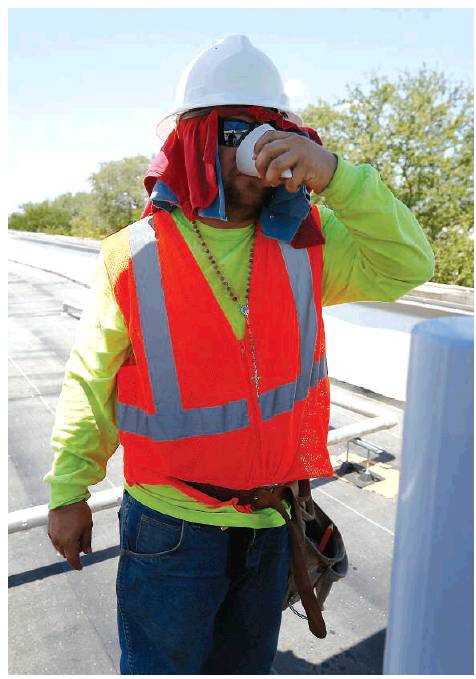

In July, Hernandez and his fellow workers with Beldon Roofing were laying white liner on a commercial building roof on Hildebrand. This summer was Hernandez’s first as a roofer, and he had to get adjusted to the heat that can turn San Antonio rooftops deadly.

Early on, “I fell out a couple times,” Hernandez said said, adding that he since has learned how to better read the signs of heat exhaustion. He takes water breaks in the shade every 15 to 20 minutes.

Hotter temperatures could be a factor in a worker, like Hernandez, deciding whether to stick with an outdoor labor job or choose another, said Aguirre, Hernandez’s boss.

“Any aspect of your work that changes, if you like it or you don’t like it, it’s going to push you off,” he said. “Heat is probably the No. 1 factor that you deal with.”

The study also predicts a 29 percent drop in crop yields — corn, wheat, soy and cotton — and a 15.7 percent increase in energy spending because hotter temperatures require more air-conditioning.

The models Rising used also predicted an uptick in heat-related deaths in Bexar County, where people already die occasionally of heat exposure — 23 of them from 1999 to 2015, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In some low-income areas of the city, private charities and the city government have teamed up to offer some relief to older residents.

In a garage next to Guadalupe Community Center on the West Side, San Antonio firefighters loaded crates of box fans to give to seniors on a hot July day. Every summer, Project Cool, a collaboration among the San Antonio Fire Department, Catholic charities and the United Way distributes more than 5,000 box fans to elderly residents, said volunteer and donation coordinator Thomas Hoog.

“We use them in the house to move the air in the house and let the air circulate,” said Mary Badillo, who moved with her husband, Esteban, to San Antonio after 40 years in Los Angeles. Though Badillo said her children helped them fix the AC in their home, temperatures still can be stifling.

Alexis Quintero, a former petroleum engineer from Venezuela who lives with his son in San Antonio, said they need the fan to get by, despite having working central AC at their apartment near the Medical Center.

“We don’t put it on every day because the electricity is very expensive,” Quintero said, explaining that his son is working at an information technology job while he awaits a work permit. “He’s paying everything, and the bills are really expensive.”

Rainfall is less certain

While the warming trend is obvious, it’s tough to say whether hotter temperatures have made San Antonio a wetter or drier city overall.

Over the past 70 years, San Antonio has had an annual average of about 30 inches of rain, though the amount swings wildly from year to year, according to weather data at San Antonio International Airport.

For example, a little under 14 inches fell in 1954 and 2008; more than 47 inches fell in 1957 and 2007.

In her report, Hayhoe looked at whether San Antonio’s rainstorms are getting more intense.

She noted an increase in the volume of rain for the wettest five days of the year from 1960 to 2014, as well as the intensity of all rainstorms, on average. But these trends weren’t strong enough to be statistically significant, she wrote.

That makes sense. Compared to temperature, which occurs over a wide area, precipitation is more “spotty” and therefore less likely to show clear trends, Mulvey said.

“It can be pouring downtown, and out on the Northwest Side, it’s dry as a bone,” he said. “We get a lot of our precipitation out of heavy storms, and those are the real spotty ones.”

Flooding data from 18 stream gauges around San Antonio show an upward trend in peak floods over the decades. However, that trend might be due to more asphalt and concrete in the city, which increases runoff.

Climate models predict San Antonio will become a drier city overall, with the rain coming in heavier storms than in the past, though scientists says future rainfall is harder to predict than temperature.

Hayhoe’s model predicts one more day of rainy weather every three to five years, with dry periods lasting one to four days longer per year. Her analysis states with “moderate confidence” that average winter and spring rains will decline as the century continues, with drier conditions in spring and longer periods of consecutive dry days.

Also of moderate confidence is that the “frequency of heavy precipitation and/or average precipitation intensity may increase across some parts of Texas,” although local factors often will make it difficult to predict rainfall for specific locations, including San Antonio, she wrote.

The model used by Cook, the UT professor, predicts a 5 to 10 percent decrease in average annual rainfall by 2050 for the Austin area, which she said also could apply to San Antonio.

“It’s always true that temperature projections are more reliable than precipitation projections,” Cook said.

Floods, droughts, wildfires

Despite being 130 miles from the coast, hurricanes still can pose a flooding threat to San Antonio. Last month, Texas confronted what an extreme hurricane looks like in a warmer world.

After Hurricane Harvey slammed into the Coastal Bend, it moved to Houston, where it dumped about 50 inches of rain in parts of Harris County over three days, shattering all previous rainfall records in North America. The National Weather Service recently released revised data for a gauge in Liberty that recorded 55 inches.

For awhile, when forecasters thought that San Antonio might be in the path, they were predicting 20 to 25 inches of rain, which would have set a record.

Local officials still are grappling with how to prepare for flooding of that magnitude. Most of San Antonio’s small stormwater structures are built to withstand 10 inches in 24 hours.

“You are trying to stop catastrophic flooding, while at the same time, our weather is getting more and more severe,” District 7 Councilwoman Ana Sandoval said at a stormwater conference. “If Hurricane Harvey came here to San Antonio, would we have been prepared? The answer is no.”

But just as it grapples with more extreme storms, San Antonio and Texas overall also could face more extreme droughts, though little research has been done on the subject.

The Texas Water Development Board, the state’s water planning authority, has not formally studied how climate change will affect the state’s water supplies, said Robert Mace, who directs the agency’s 70 scientists and engineers.

One alarming forecast calls for more frequent and severe droughts. One 2010 study published in the Texas Water Journal foreshadows multi-decade droughts, especially in West Texas and the Panhandle starting around 2060. The authors compared future droughts using three three climate models.

“Taking into account the range of uncertainties associated with the different models, the results indicate West Texas has the potential to become much drier than it is at present,” the study states.

In a chapter of the 2011 book, “The Impact of Global Warming in Texas,” UT researcher George Ward analyzed how climate change will affect Texas’ ability to store water.

Most of the water Texans drink is stored in reservoirs, and the state has at least 195 of them. The hotter the temperature, the more water evaporates from the surface. By 2050, between 19 percent and 29 percent more water will evaporate from Texas reservoirs compared to the year 2000, Ward wrote.

In Central Texas, that includes reservoirs serving San Antonio, Ward predicted 20 percent to 32 percent more evaporation.

State water law does require local water planners to plan based on extremes of the past. Most use Texas’ eight-year drought of the 1950s, the longest ever recorded.

The San Antonio Water System goes further, planning for the length of the drought of the 1950s with the intensity of the recent 2009-2015 drought.

Compared to other cities that rely only on rivers and lakes, SAWS’ water supplies are more secure because most comes from underground, SAWS vice president Donovan Burton said.

“We’re really well accommodated for any changing conditions in climate because we’re a groundwater-based system,” he said.

Lack of rainfall and drier soils also can lead to more fires. Northern Bexar County already has some of the highest fire risks in the state, according to the Texas A&M Forest Service.

In the Hill Country, a region that used to feature more open grassland, European-American settlement and fire suppression have let the forests thicken. Much of the terrain now is covered by densely packed live oak and juniper thickets with lots of flammable grass in between, said Tom Spencer, who heads the service’s Predictive Services Department.

“It’s one thing if you’re dealing with grass fuels like 100 years ago,” Spencer said. “Junipers and oaks … burn with very high intensities. They are very problematic and very hard to control.”

Built-up fuels played a role in the 2011 Bastrop County Complex Fire, the most destructive in Texas history, which destroyed nearly 1,700 homes and killed two people.

Paradoxically, hotter and drier weather eventually could make San Antonio less fire-prone.

In a recent study now undergoing peer review, University of Missouri forestry researcher Michael Stambaugh and colleagues at the U.S. Geological Survey plugged data from three different climate models into another model that predicts forest fire probability.

“San Antonio is right in the transition zone,” Stambaugh said. “It could probably go either way, depending on the climate recipe.”

Short-term droughts can raise fire risks by drying up fuels, but over the long term, a drier climate means fewer plants and trees to burn, Spencer said.

“You see these big fire seasons … they generally followed years of normal to above-normal moisture where you had a lot of grass, a lot of fuel on the ground,” Spencer said. “But if you have multiyear droughts, you see the fire numbers back off because the lack of fuels on the ground.”

An increase in heavy rains will bring its own disasters in a region already known as Flash Flood Alley.

From 1993 to 2014, the city endured 129 floods that killed 16 people and caused 507 reported injuries and property damage totaling almost $14.7 million, according to the city’s SA Tomorrow Sustainability Plan.

That’s not the only kind of flooding that will affect the city. Scientists also are warning of flooding from sea level rise on the Texas Coast, where NOAA is predicting a little more than 3 feet of average sea level rise by 2060.

That kind of flooding could spur migration to inland cities like San Antonio, according to a recent modeling study published in Nature Climate Change. The model assumes a business-as-usual approach to the climate with no efforts to adapt coastal communities to rising seas.

By 2100, 50,000 to 200,000 people could move to the San Antonio-New Braunfels metro area exclusively because of sea level rise, according to the study that relied on a model that describes human migration.

Changes in nature

Climate change isn’t all havoc and mayhem. Some changes are subtle, noticed only by those who can read nature’s signs.

Georgina Schwartz is a member of the San Antonio Audubon Society who has been birdwatching here for 44 years. Over that time, she’s noticed that birds once more common in South Texas are shifting north into Bexar County.

Just one example: local birders would get excited years ago about seeing cinnamon teal, a reddish brown duck, at Mitchell Lake in winter, she said. Maps of the duck’s range shows that it winters in deep South Texas, Mexico and South America.

“Now we have them every winter,” she said.

Other birds more common in South Texas and Mexico are moving into the area, too. Schwartz said she has noticed more crested caracara, Hutton’s vireo, Audubon’s oriole and great kiskadee in Bexar County.

That also includes a small, black, orange-eyed water bird known as the least grebe.

“I got my first one in the Lower Rio Grande Valley eons ago,” Schwarz said. “Now they are at the bird pond at Mitchell Lake almost every time we go there. They clearly have nested there.”

Even the local flora is changing. Since 1990, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has revised its Plant Hardiness Zone maps, which guide gardeners and arborists in choosing species that can survive frosts. The revision added a warmer zone to San Antonio for the first time.

In the 1990 map, based on weather data from 1974 to 1986, San Antonio fit within a zone where winter’s lowest temperatures average 15 to 20 degrees. In the latest edition, based on another roughly 30 years of data, another zone where low temperatures average 20 to 25 degrees has crept into southern Bexar County.

James Spivey, general manager of the tree farm, Peerless Farms, in Frio County, hasn’t done any scientific studies on how trees and plants are responding to climate change, but he has noticed a shift in his decades of experience.

Larger trees like live oaks and pecans struggle more during hot periods, and tree diseases like oak wilt are spreading more rampantly. That’s probably due to a combination of factors, especially a lack of water.

“The bottom line is they got one choice, either they adapt to it or they die off,” he said. “It’s not just the 1 degree or the 5 degrees hotter than normal. Without sufficient water, they will die.”

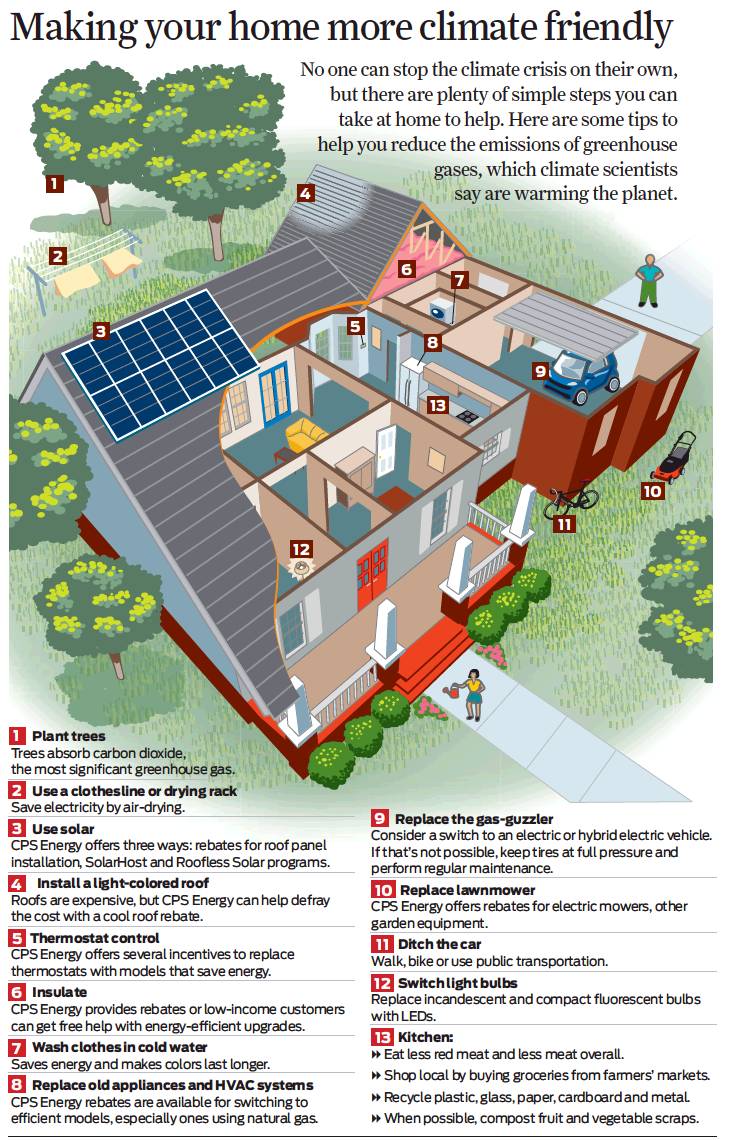

San Antonio’s climate push

For the first time, local leaders in San Antonio are talking seriously about how to respond to global warming.

It started in June, after the city elections that ushered in Mayor Ron Nirenberg, long seen as a champion of environmental causes, and Sandoval, who has a background as an environmental engineer and climate expert.

The first step the council took was signing the Mayor’s Climate Pledge, a commitment to uphold the goals of the international Paris Climate Accord.

President Donald Trump had threatened to pull the U.S. out of the accord, though administration officials since have put out conflicting messages about the pull-out. A coalition of local environmental and social justice groups had for weeks urged Nirenberg’s predecessor, Ivy Taylor, to adopt the pledge.

“We feel really good about the Paris Climate Accord, but the reason we keep talking about it is it needs action,” Nirenberg said at a forum Friday at the University of Texas at San Antonio with CPS Energy CEO Paula Gold-Williams and UTSA President Taylor Eighmy.

“The majority of council is going to set policy and make it law that we become a more resilient community,” he said.

What that means exactly still is an open question. In June, Nirenberg and CPS Energy officials announced the utility will give $500,000 to UTSA to draw up an outline of a climate action plan and an inventory of greenhouse gas emission sources in San Antonio.

“We are at this wonderful nexus of forward-looking thinking and putting a lot of things together,” Gold-Williams said.

The foruml ended with an announcement of another nearly $970,000 in funding to UTSA’s Texas Sustainable Energy Research Institute for work on four technical research projects, part of a 10-year, $50 million agreement forged in 2010.

City officials have said they want the climate action plan to be community-led. On Oct. 18, city Chief Sustainability Officer Doug Melnick will join Texas State Climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon and other climate experts at San Antonio College’s Eco Centro for a public panel discussion on what that plan might look like.

The environmental groups also are working hard to get more people engaged. One Sierra Club-sponsored event on Aug. 23 at Five Points Local featured a panel discussion along with music, poetry and food centered on coping with extreme heat.

At the UTSA event, District 8 Councilman Manny Palaez talked about seeing around 30,000 people from all across San Antonio gathered in the Alamodome for a Guns N’ Roses concert earlier this month. What might it look like, he wondered, if that many residents were working on issues of sustainability and climate change?

“If we can get 30,000 people engaged on these issues, we would have solutions,” he said. bgibbons@express-news.net |

For the first time, local leaders in San Antonio are talking seriously about how to respond to global warming.

16 Average annual number of 100° days in San Antonio over past 30 years

174 Actual number of 100° days in San Antonio so far in this decade

40 Almost 40 percent of the Texas labor force is outdoor labor

2.4° Rise in average San Antonio temperature since record-keeping began in 1880s