WHAT AND WHY R.I.

Not gone after all

The search to find what’s left of one of Rhode Island’s most historic buildings

By Paul Edward Parker Journal Staff Writer

IPAWTUCKET love a good mystery, but before I can tell you about this one, I have to confront an uncomfortable truth: Reporters sometimes get things wrong.

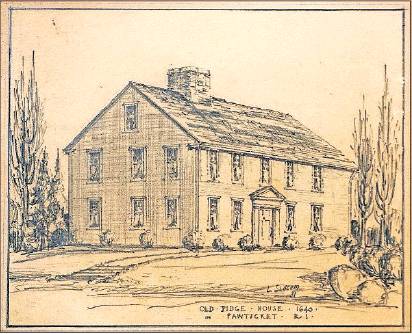

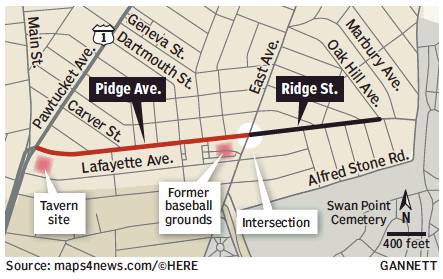

Case in point: I wrote a story in the Jan. 19 Sunday Journal about why the name of Pidge Avenue in Pawtucket changes to Ridge Street when it crosses East Avenue. Part of that story revolved around the history of the Pidge House Tavern, a building that dated to 1641, a pub that George Washington visited during the Revolutionary War and the Marquis de Lafayette used as his headquarters.

I reported that the Pidge House was torn down in the 1950s, when a billboard company headed by Granville Standish owned the property. A Journal clip from 1954 described the demise:

“Decay Claiming Oldest R.I. Building,” the headlines read. “Pidge House on N. Main Street Is Crumbling.”

And in 1961, The Journal reported on a talk given by preservationist Paul Fournier about a proposed “Preserve Old Pawtucket” project.

“The expert added that the city had few historical buildings left, recalling that some years ago the old Revolutionary Pidge Tavern had been swept away by wrecking crews,” the story reported.

So there you have it, I concluded, the Pidge House was history.

But what if a significant portion of what had been considered the oldest building in Rhode Island had eluded the wrecking ball and survived into the 21st century?

Soon after my Jan. 19 story appeared online, I began getting email from readers suggesting that part of the tavern might still be around.

“It is said to have some beautiful woodwork and paneling on the interior,” Bruce Tillinghast wrote me. “When the building was taken down someone removed several rooms to save the paneling.”

Old newspapers, collected during my research on the first story, gave a tantalizing clue.

On a couple of days in October 1977, someone placed advertisements in The Providence Journal, offering “executive” office space “adjacent to off- and on-ramps at I-195 at Gano Street, India Point, Providence.”

What made this office so special?

“Office features historic pine paneling, beams, and working fireplace from original Pidge House Tavern (circa 1640),” the ad read.

And it had a contact name, Raymond LaBelle, and a phone number.

It wasn’t much of a lead, but it was the only one I had.

So I called the number.

“Good afternoon, Lamar,” a cheery woman answered.

Instantly, the plot of this mystery thickened. Lamar is a billboard company, just like Granville Standish’s company was when it owned the tavern.

I was switched to Mike Murphy, and I explained why I was calling the number in a 40-something-year-old newspaper ad and looking for Raymond LaBelle.

Murphy said he knew of LaBelle. He would try to contact him for me. I should check back in a week.

Meanwhile, I had heard from another reader, Stephen Brennan, who told me about a book, published in 2012, about historical taverns in Rhode Island, including a section about Pidge Tavern.

“According to the book, when the tavern was being demolished the tavern taproom, the stairs going up and one upstairs bedroom [were] saved and moved to the Standish Building in India Point,” Brennan wrote. “When the company closed in the ‘60s, the building was also torn down.”

Not good, but Brennan continued, “An employee realized the value of the taproom and stuff and pulled it all out prior to the demolition. But nobody knows what happened to it.”

So, I went to Amazon to get a copy of “Historic Taverns of Rhode Island” by Pawtucket historian Robert A. Geake, who, coincidentally, lives on Pidge Avenue.

“Only recently did it come to light that the room was dismantled once again and has remained in storage for over fifty years,” Geake reported in his book, attributing the information to a former sales representative at Standish Barnes, one of several names Granville Standish’s company would acquire over the years.

A promising lead. I tracked down Geake to see what he could tell me of this employee.

“I am not sure if he and his wife are still in Rhode Island,” Geake emailed me. “Let me try to locate them and get back to you.”

While I waited to hear from Geake, Murphy put me in touch with Raymond LaBelle.

I called LaBelle on Jan. 23.

“What became of the Pidge Tavern interior?” I asked him.

“I haven’t the foggiest idea,” he told me, pointing out that it had been more than 40 years since he placed the ad as leasing manager for the billboard company, when he oversaw lots of properties.

I wasn’t sure that I believed LaBelle. If the accounts of the reconstructed room were true, this office was a showpiece in his company’s headquarters, not just another property under his care.

But there wasn’t much I could do except wait on Robert Geake to track down the source he quoted in his book. I discounted the possibility that LaBelle was Geake’s source. LaBelle was the leasing manager for Standish at the time, while Geake’s source was described as a sales representative.

More than two weeks passed, and I heard nothing from Geake. I looked him up on Facebook and found that he was scheduled to give a talk on Feb. 9 for the East Greenwich Historic Preservation Society about gravestones. I decided to show up and see what he might tell me face-to-face.

Two days before Geake’s talk, I went to lunch at the food court in the Providence Place mall. When I returned to my office the red message light on my phone was lit.

“Paul, good afternoon,” a familiar voice announced. “It’s Ray LaBelle calling. You contacted me regarding the Pidge Tavern.”

He left his phone number and invited me to call.

“I hadn’t heard that name in years,” he explained when I talked to him the second time.

This time, his memory refreshed, he flooded me with so much detail that I had to ask him to slow down so I could take notes of it all.

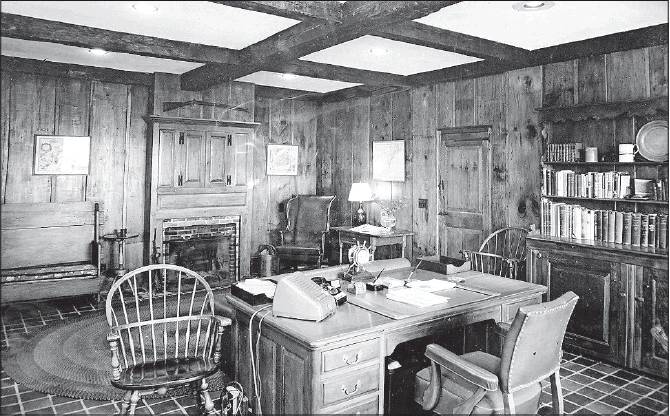

“The wood from the Pidge Tavern was essentially set up at the Standish Johnson Company,” LaBelle said. “It was the executive office of the president.”

LaBelle had been in the room, on India Street in Providence, decorated with Pidge Tavern wall paneling and floorboards. “It looked like old wood,” he said. “It was raw wood.” It hadn’t been highly polished or fancied up.

Did he have any pictures of the room?

“No,” he told me. “At the time, it wasn’t that important.”

LaBelle related a brief history of Standish Johnson, the company that, under Granville Standish, had owned the Pidge House at the time it was torn down. He told me how Howard M. Johnson later sold the company to Richard J. Deeble, who was president when LaBelle saw the office decorated with paneling from the Pidge Tavern. Deeble later sold the company to Whiteco Industries.

“Of course, all these people I’m talking about are dead,” he told me.

“Wonderful!” I thought.

LaBelle went on, alluding to what happened after Whiteco bought the company in 1983, which I fleshed out with clips from The Journal archives. In 1986, the real estate on India Point was sold to Harborview Landing Associates, which then sold to a developer group headed by Peter J. Rotelli.

Rotelli’s group razed the building in 1988 to build a Comfort Inn, which later became the Hilton Garden Inn.

LaBelle was no longer connected to the company by then; he had left and taken state jobs, working as director of emergency management, then director of the 911 system before retiring about 10 years ago to Narragansett.

I asked whether LaBelle knew what happened to the Pidge Tavern pieces when the building was torn down.

“I believe it was taken out,” he said.

“Do you know who took it out?” I asked.

He said that he believed it was Deeble’s son-in-law, Robert Brown, who worked as operations manager for Standish Johnson. LaBelle said it had been a while since he had spoken to Brown. He said he believed Brown might have moved to California, but that the family had a farm in the Greene section of Coventry, along the Connecticut border.

“That’s about it,” LaBelle summed up his knowledge about the Pidge House remnants. “Where they ended up, I have no idea.”

But now I had a new lead to run down!

First, though, I wanted to talk to Robert Geake. Was Robert Brown his source who knew where the Pidge Tavern pieces were kept in storage? Did he know how to contact Brown? Brown, of course, was operations manager, according to LaBelle, where Geake had described his source as a sales representative.

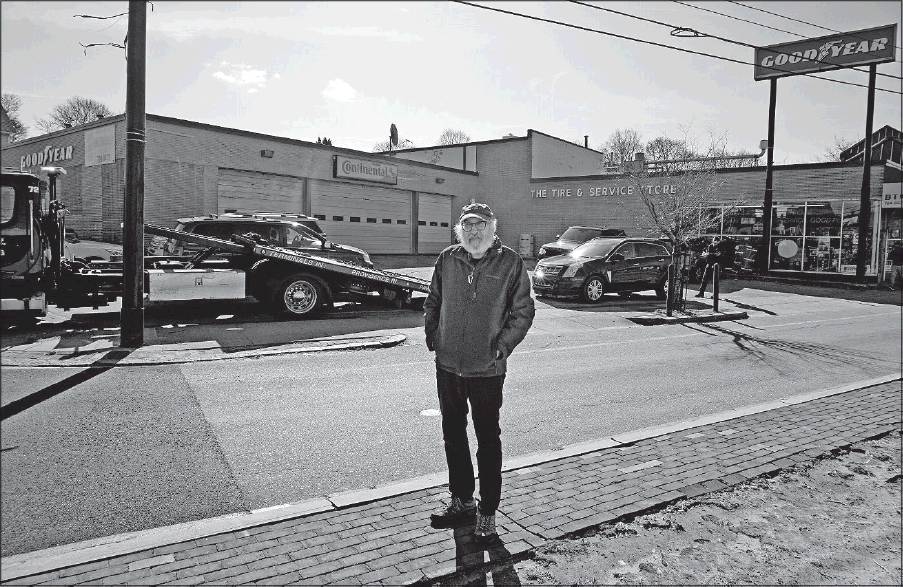

Snowflakes fell as I pulled into the parking lot of the East Greenwich police station. A side hallway led from the lobby of the station to a community room, where plastic chairs had been set up in neat rows and a small crowd munched on cookies and other treats. I arrived shortly after historian Geake’s presentation had ended, and a handful of people clustered around a white-bearded man at the front of the room. That had to be Geake.

I approached him and introduced myself as the reporter who had been looking for information about the Pidge Tavern and about the man mentioned in Geake’s book who might know the whereabouts of the tavern’s remnants.

“Have you been able to get in touch with him?” I asked.

“No,” Geake replied. “I think he moved to Florida.”

“Can you tell me his name?”

“Chuck Healey.”

Geake related a story of Erika Wallingford, who had run a used bookstore in the plaza at the East Avenue end of Pidge Avenue. At the time, Geake worked there part-time, and Wallingford invited Geake to dinner at her home one night. Her husband, Healey, entertained the historian by describing his encounter with the Pidge House Tavern, when it was set up at Standish Barnes.

“He worked for the company,” Geake told me. “He remembers it being installed. He remembers the tavern license. It was just as though they had just left it. There were still mugs.”

Geake told me more about Healey and the Pidge Tavern room at Standish Barnes: It included a stairway from the tavern building that led to a second floor in the office building, Healey had told him. “He was there when it was removed. He said it went back to the family. After that, he doesn’t know what happened to it.”

Now, I had two leads to run down: Robert Brown and Chuck Healey. But which one to chase first? My gut told me that a guy named Chuck Healey married to an Erika Wallingford would be easier to track because their names were less common than Robert Brown. On the other hand, I had a feeling that while Healey might have seen the Pidge Tavern decor, Brown, as son-in-law of the company president, was more likely to have taken possession of it when it “went back to the family.”

But it turned out that Chuck and Erika were pretty elusive.

Google and the usual online people search tools came up empty. So did the voter registration databases for Rhode Island and Florida. So did a search of obituaries.

I turned my attention to Robert Brown.

Raymond LaBelle had described him as son-in-law of Richard Deeble, the Standish Johnson president whose office in the company headquarters had been decorated with the tavern interior. I wanted to learn more about the family, hoping there would be clues to Brown’s whereabouts.

I hit paydirt almost immediately.

On July 26, 2009, The Journal carried Deeble’s obituary. A resident of Greene, Deeble died at age 86. Among his survivors were his daughter Victoria Brown and her husband, Robert Brown. The obit said they lived in Greene. But it had been published 10 years ago, so all bets were off.

But a name like Victoria (Deeble) Brown couldn’t be too hard to trace, right?

Online people searches showed Victoria Brown in Greene and in Palm Desert, California. But I couldn’t locate a good phone number or email address.

Searching on the Greene address, on Barbs Hill Road, showed that one of the “occupants” was Standish Johnson Company.

I thought the company had been sold in the 1980s, but a quick Google search pointed to an active website. The website showed that, when the company sold its Rhode Island headquarters, it stayed in business selling billboards in eastern Connecticut. The website listed a company phone number.

So I dialed.

“Standish Johnson,” a woman answered.

I identified myself and told her I hoped she could help me solve a historical mystery by getting me in touch with Robert Brown.

She said she knew how to contact him, but wanted to know more about the mystery before agreeing to help.

So I summarized the story of Pidge Tavern’s demolition and that pieces of it had been moved to the Standish Johnson headquarters, then moved again.

“People I’ve talked to have suggested that Robert Brown might know where those pieces are now,” I told her.

She told me to send her an email to confirm my identity.

I asked who I was talking to.

“Stephanie Blue,” she told me. She said she was related to Brown, but didn’t want to say more right away.

I quickly composed an email and sent it off to her.

That was Feb. 11. I couldn’t wait to hear back.

But I would have to.

While I waited, I did more research in The Journal’s archives.

First, I re-read Richard Deeble’s obituary. It listed Stephanie Blue, of Greene, as Deeble’s granddaughter. That would make Robert and Victoria Brown her parents, or at least her uncle and aunt.

An April 1981 story reported a fire at Deeble’s Pondbrook Farm estate on Barbs Hill Road.

“The house and its contents were destroyed,” police detective Capt. Richard J. Vierra was quoted saying. “The insurance company says it’s a total loss.”

The fire, according to the article, had been reported by Vicki Brown and her husband, who lived next door.

Were the remnants of the Pidge House Tavern destroyed in the fire? In 1977, when Ray LaBelle placed the ad for executive office space, it seems they were still in India Point. But that was four years before the fire. When were they removed from the Standish Johnson building?

I went back and re-read Geake’s book, which said the tavern remnants had been removed in 1962. That seemed unlikely, but, if true, it meant they could have been in the farmhouse when it burned down.

I sent Stephanie Blue a follow-up email the day after my first email. And then, the day after that — and several more days after that — I tried calling again.

All my efforts were met with silence.

After a week passed, I decided to head down to Greene and pay her a visit.

I jumped on the interstate. Downtown Providence rolled by, and then the suburbs of Cranston, Warwick and East Greenwich gave way to the countryside. The interstate gave way to state routes and local roads. Past the old Rice City Tavern and Rice City Church, the pavement of Vaughn Hollow Road gave way to the dirt track of Barbs Hill Road. It felt like driving back in time.

Drizzle dotted the windshield, and mist played among the trees in the forest at the side of the road. I finally came to a dirt driveway flanked by two stone pillars. I paused for a moment. This would be the end of the road. Would I find Stephanie Blue? Would she be helpful? Could the remnants of the Pidge House Tavern be just down this driveway?

The driveway meandered a quarter-mile down hillside farmland into a hollow, where a small village of a half-dozen buildings clustered beside a pond.

One of the buildings had several vehicles parked nearby. Dense white smoke poured from a red-brick chimney. I headed that way.

As I approached, a burly, bearded man came out of the building.

I rolled down the car window. “I’m looking for Stephanie Blue,” I told him.

“Who are you?” he challenged.

“Paul Parker, from The Providence Journal.”

“Does this have to do with that street name?” he asked, referring to my original story about Pidge Avenue and Ridge Street.

I told him it did.

He motioned to an area next to an adjacent building. “Why don’t you pull over there somewhere and park and come on in?”

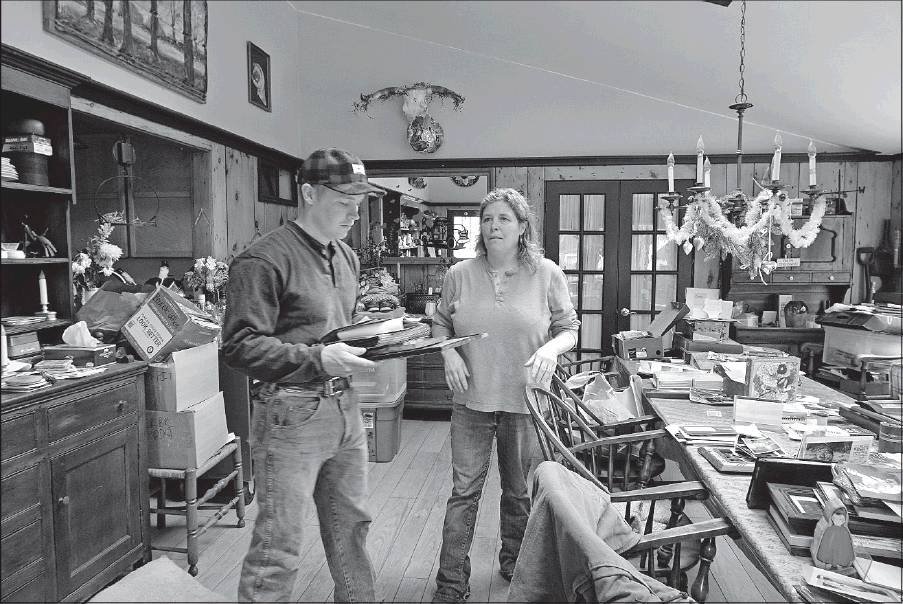

When I got inside, he offered his hand and introduced himself as Ben Blue. And then he introduced his wife, Stephanie.

She apologized for not getting back to me sooner — she had been out of town and just got back that day. She invited me to the house next door, where she had some Pidge Tavern memorabilia.

She showed me a framed liquor license, issued Sept. 27, 1783, by the North Providence Town Council — Pawtucket was part of North Providence then — to Jeremiah Sayles, who owned the tavern before it was inherited by his daughter, Abby Sayles, who married James Pidge.

Blue flipped through an album of old photos of the Standish Johnson headquarters at India Point.

“This is all Pidge House.” She pointed to a photo of her grandfather’s office, which had been decorated with pieces from the Pidge House interior.

Blue had gone to high school at The Wheeler School, making daily trips from Coventry to the school’s Providence campus.

“I spent a lot of time before school in that office, and after school waiting for a ride home,” she told me.

Historical surroundings had been like home to Blue growing up.

“Most of my friends lived in houses built in the 1700s,” she said. “These were all places I played.”

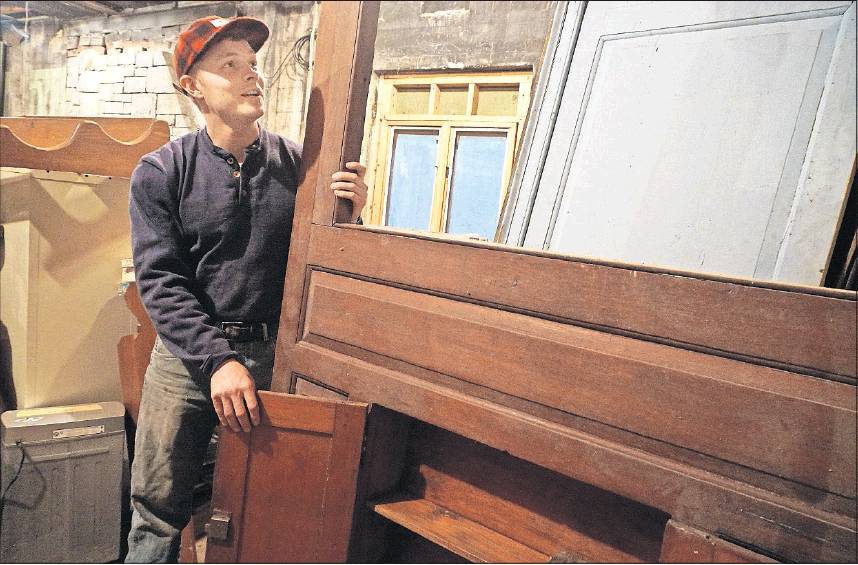

As we talked, her son Remington Blue pulled up outside the house in a van. He led me to the house next door, the one that had belonged to Richard Deeble at the time of the 1981 fire. It now was the home of Robert Brown, when he wasn’t in California.

Remington Blue — Rem for short — led me through the first floor to wooden stairs that turned a corner as they led down to the basement. We passed a steel vault door, and then went down three concrete steps to a lower level of the basement.

The room we entered was spacious, with high ceilings. The floor was tiled. The walls were blue-green in color, with black marks here and there, reminders of the fire that, despite Capt. Vierra’s pronouncements to the contrary, had not destroyed the farmhouse.

Rem pointed to some sheets of plywood leaning up against a back corner of the room.

“It looks like there’s some old wood in the back,” he said.

When Rem pulled the plywood out of the way, he revealed old wooden paneling and doors painted light blue. Most of the tavern parts were single planks in the neighborhood of seven or eight feet tall. A few had been assembled to other parts, forming basic pieces of cabinetry. While some were fastened with hand-hammered nails that could well be hundreds of years old, others had clearly modern hardware, even a plastic-mounted magnetic door latch.

This collection of boards is what remains of the tavern that was built in 1641, that played host to George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette and that lent its name to a curious avenue in Pawtucket before falling to the wrecking ball in the 1950s.

Stephanie Blue feels a duty as the custodian of these literal pieces of history and has a plan for what remains of the Pidge Tavern.

Her husband, Ben, had bought an old building just down the road in the village of Rice City. It is the old Rice City Tavern. It has a pedigree much like the Pidge House Tavern. It was a major lodging stop on the main road from Providence to Norwich, Connecticut, just as Pidge was for travelers to Boston. And, much like Pidge in the 1950s, it has seen better days.

“It’s in horrible condition,” Stephanie Blue told me. “It’s completely unlivable.”

But the Blues plan to renovate it, including installing the paneling from the Pidge House Tavern.

After that, they aren’t sure. Much will depend on zoning regulations an whether and inn or tavern would be permitted.

“I can’t wait to do it justice,” Stephanie Blue said. pparker@providence journal.com , (401) 277-7360 On Twitter: @projopaul