Helping & heeling

Dog-training program offers positive opportunities for inmates

BY MATT PATTERSON

Staff Writer mpatterson@oklahoman.com

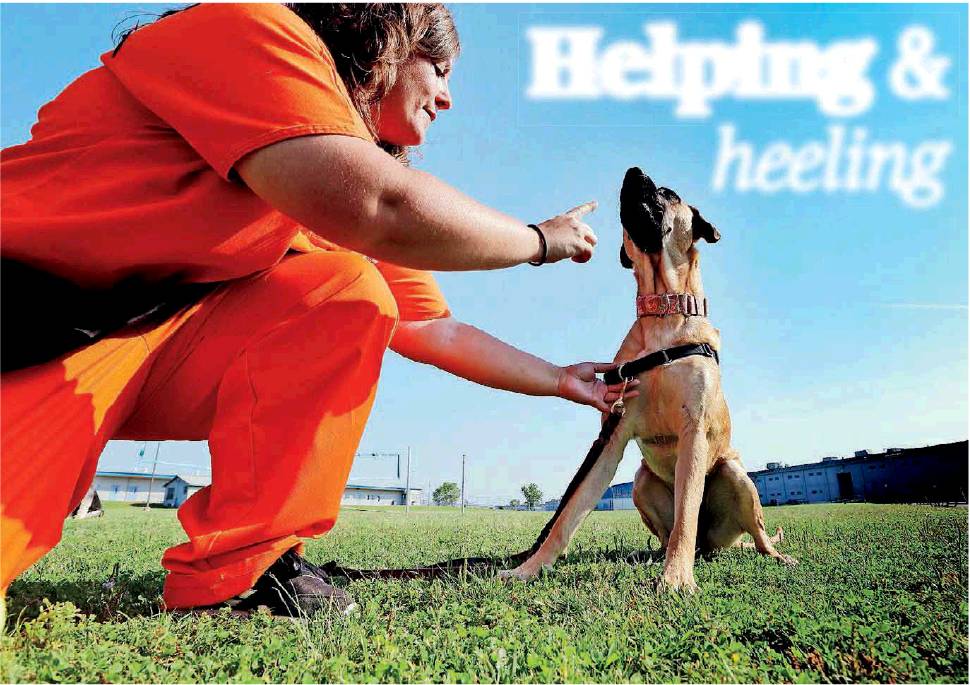

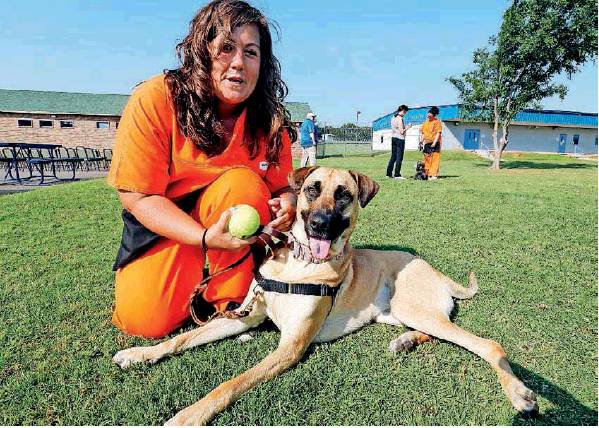

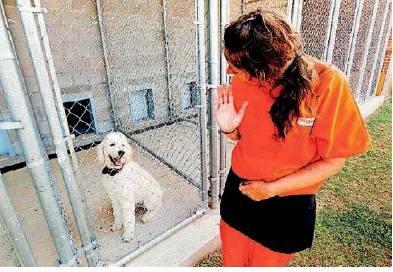

MCLOUD — Lacey Wallace and her dog, McAlister, seem a natural fit. Playing on the grass, the 28-year-old trainer demonstrates some of the rambunctious pooch’s talents. If not for her orange jumpsuit, the surrounding walls and the ever-present gaze of prison guards, Wallace would look like any person hanging out with their dog on a bright spring morning.

“I love having a dog in my room,” Wallace said. “It makes it feel a little less like prison and makes me feel a little more human.”

Mabel Bassett Correctional Center is a mediumsecurity women’s prison that is home to about 1,000 inmates, and about a dozen or so dogs of various breeds. At the edge of the prison's massive central yard is the newly opened Serelda Cody Dog Training Facility.

The 3,000-square-foot facility is the centerpiece of the Guardian Angels program, a combined effort of the Department of Corrections, Friends For Folks and CareerTech. It aims to help prisoners fill their time constructively, while also training dogs for private owners and those in need of service animals.

And that’s how Wallace spends her days.

From 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. with a break in between for lunch, she’s training McAlister who will eventually go back to its owner after six weeks in the program, to sit, stay, lay down, heel and come, among other skills.

“I thought it was really hard when I first started,” Wallace said. “I was nervous because I didn’t think I would be able to train a dog. But once you get in and train your first it becomes natural.”

''I love having a dog in my room. It makes it feel a little less like prison and makes me feel a little more human.”

Lacey Wallace

Wallace will have to wait to play with a dog of her own. In prison on drugs and weapons charges, she isn’t up for parole until late 2019. She has a lot of time on her hands.

“I wanted to change my life, to do something with my time here and give something back,” she said. “These dogs, some of them come in on their last legs, or they have a behavioral issue that might force their owner to give them up. We train them and they get a chance.”

The new facility has 10 indoor-outdoor kennels, a grooming room and a classroom. Outside is an expansive obstacle course. Such programs aren’t new.

Despite battling cancer, Sister Pauline Quinn had to be there when the facility at Mabel Bassett opened, traveling from Green Bay, Wisconsin, with her service dog, a golden retriever named Pax. Quinn, 75, founded Pathways to Hope in 1981 and introduced the first prison dog-training program that same year in Washington.

Since then, she’s helped get programs off the ground at dozens of prisons in the United States and South America, even if the start was a bit rocky.

“With the first program the DOC was afraid the inmates would train the dogs to attack the guards,” Quinn said. “But you can’t train a dog to attack unless you agitate it. And if you’re agitating it, everyone will know. It’s come a long way since then.”

Oklahoma is a perfect place for programs like the one at Mabel Bassett, Quinn said. The state's female incarceration rate leads the nation and is twice the national average. While some might think prison should be made as difficult as possible, Quinn sees little value in that approach.

“Warehousing without purpose is not a good practice,” Quinn said. “That’s been proven over and over again. They have to take responsibility for their actions, but they also need to have the opportunity to heal and this is one way to do that.”

Annie the mascot

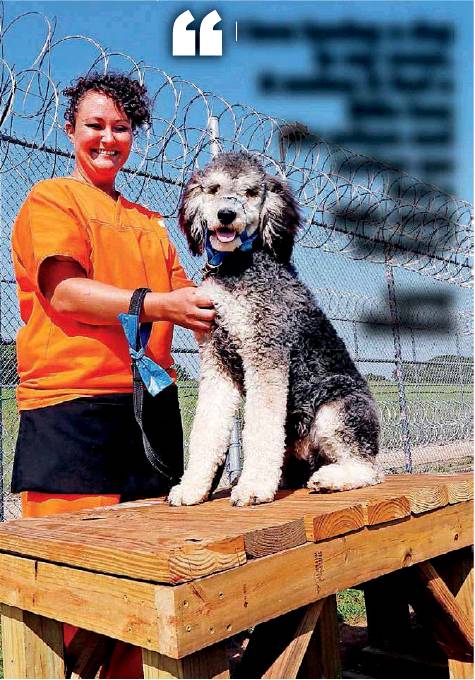

As inmate Kimberly Wenthold plays with Annie Bassett, the program’s official mascot dog, what Quinn is talking about becomes obvious.

As the playful German shepherd mix bounces up and down, barking and running in circles, Wenthold drops to the ground and tries to get her to calm down. She’s had Annie for a year, and the dog will remain at Mabel Bassett for the rest of her life.

“We use her a lot for demonstrations,” Wenthold said. “And she’s really good at reading other dogs. She gets along with everybody.”

When Annie came to Mabel Bassett she was in bad shape, not unlike her human counterparts.

“She had sutures in her ears and she was underweight,” Wenthold said.”

Wenthold will have a chance to make her mark on the program for years to come. On Sept. 2, 2013, Wenthold, under the influence of Xanax, was driving along State Highway 9 near Norman when she caused an accident that claimed the life of 8-yearold Cadence Gordon.

The 33-year-old has 16 more years before she’s eligible for parole on a 23-year sentence. Like Annie, she came to prison at the lowest point of her life.

“The program teaches us all dogs have a second half, too,” she said.

When she arrived at Mabel Bassett three years ago, Wenthold jumped at the chance to be around dogs.

“I said yes, but I had no idea what a life-changing experience it would be for me,” she said.

Annie is with her 24 hours a day.

“Not only did I help her get through so much, she’s helped me get through so much, too,” she said.

Worth the effort

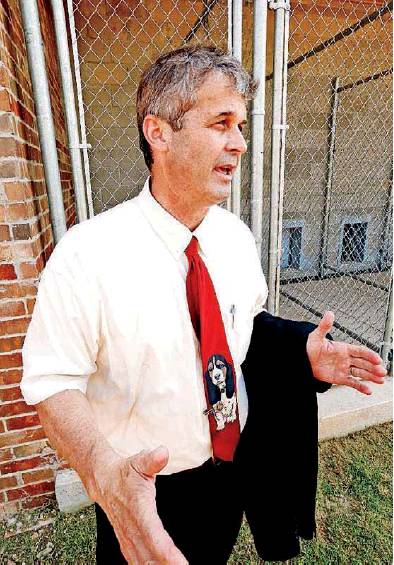

Norman veterinarian John Otto knows some people might oppose programs like Guardian Angels. His own dad needed convincing when Otto started volunteering at Lexington Correctional Center. He visited the prison for two years before telling his father.

“My dad was in the FBI for 30 years, and he was of the belief that you just lock them up and throw away the key,” Otto said. “But the reality is 96 percent of offenders get out. If we don’t change how they behave they’ll do the same thing. They are human beings and we have to treat them as human beings.”

Otto helped raise more than $400,000 for the new facility. The construction was harder than normal, a five-year process filled with obstacles unimaginable in most construction projects, he said.

“We had 14 bricklayers who were rejected from doing one of the walls,” Otto said. “Thomas Edison had 10,000 tries to create the lightbulb and I’m thinking man, I don’t have 10,000 tries.”

The effort was worth it. At the building's May 29 dedication, prisoners approached Otto one by one to thank him. Hugs and handshakes aren’t allowed, but the appreciation was obvious.

Quinn’s out-of-the-box idea that came to life in 1981 has sprouted 100 programs in 38 states that pair prisoners with dogs.

“This is a beautiful program because animals give unconditional love,” Otto said. “They don’t judge. When you have that kind of thing going on the inmate becomes comfortable and starts to talk, to open up. And then they start learning. Through learning their self-esteem moves up.”

Corrections officer Sgt. Danny Pianalto has seen how being around that kind of unconditional love helps inmates live for something beyond marking off another day on the calendar.

“The ladies in the dog program are second to nobody when it comes to their dedication and enthusiasm,” he said.

Programs like Guardian Angels make Pianalto’s job a little easier. Structure is part of that, but the sense of accomplishment is where he sees the biggest benefit. He enjoys seeing the smiles when a dog has successfully completed its training.

“The inmates get a sense of self-satisfaction,” he said. "Their vision for that dog has come to completion.”

Heather Hood’s latest dog is 9-month-old poodle named Boomer. When Boomer is finished with his training he’ll go back to his owner who wanted the dog to learn better manners.

Hood's favorite projects are helping dogs stay in their homes.

“My first dog was ‘Please help me fix my dog or I’ll have to get rid of them’,” she said. “I kept the dog for eight weeks and when it got home they ended up keeping it.”

It was one of her greatest accomplishments.

“It makes me feel great knowing I was able to help that dog, another being,” she said. “I never in my life have been able to have that feeling. It was right up there with giving birth to my kids.”

Hood welcomes the regimentation of the program. She believes it will help her get back on track when she’s finally released.

“These are qualities I lacked out there,” she said. “That’s one of the reasons I was in the lifestyle that I was in.” As Boomer comes up behind her, Hood turns her attention to the curly haired dog, his big brown eyes staring up at her.

“I can come out of prison with more ability to make it in the world and succeed,” she said. “The program gives every one of us hope. You don’t feel like it’s the end of the road.”

''This is a beautiful program because animals give unconditional love. They don’t judge. When you have that kind of thing going on the inmate becomes comfortable and starts to talk, to open up. And then they start learning. Through learning their self-esteem moves up.”

Dr. John Otto, Norman veterinarian and program volunteer