Arkema: Act of God or crime?

Jurors will weigh the arguments during a criminal trial expected to take six weeks

By Samantha Ketterer STAFF WRITER

Carla, Alicia, Allison, Rita, Ike.

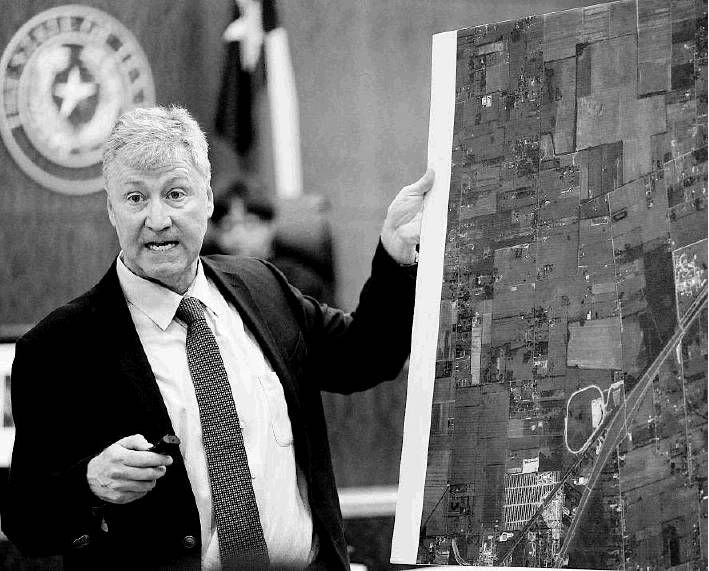

Never did Arkema Inc. remove its Crosby plant’s stockpile of hazardous chemicals amid those storm systems’ threat of rising floodwaters, special prosecutor Michael Doyle said.

With Hurricane Harvey, Arkema’s luck ran out, he said Thursday during opening statements of the criminal trial against the company and some of its leaders. Doyle argued that the company’s long-standing pattern of recklessness put the public in danger and made fear a reality: Water mounted within the 100-year and 500-year floodplain where the plant sat, cut off power at the facility and caused organic peroxides on site to combust.

More than 200 residents were evacuated from the area for about a week, and two sheriff’s deputies fell ill. In all, 23 people were briefly hospitalized from the fire’s resulting emissions.

“They always choose to leave the product at risk,” Doyle said. “They were never going to move a single gallon away.”

Attorney Letitia Quinones countered Doyle’s representations during her opening arguments for Arkema, calling Harvey “the most natural disaster” and listing a number of precautions the company took before the situation became unmanageable.

Arkema’s attorneys argue that the storm was an “act of God,” meaning that the company shouldn’t be criminally liable for the harm that resulted.

And Quinones hit back on allegations of long-standing recklessness. In all of the prior storm systems that Doyle named, the Crosby plant never flooded and the organic peroxides never decomposed, she said.

“Why would we move 350,000 pounds of organic peroxides into the community and on the streets?” Quinones said. “For the last 20 storms, these policies, these procedures, they worked.”

Quinones was one of nine high-powered defense attorneys who crowded the well of the courtroom, fighting a slate of charges against the French company’s American subsidiary, two of its executives and a Crosby plant manager.

Arkema and its then-vice president for logistics, Michael Keough, face charges of assault on the two peace officers – a rare use of the law to prosecute apolluter, experts have said. The state is also pursuing felony reckless emission charges against the company, CEO Richard Rowe and plant manager Leslie Comardelle for releasing toxic chemicals.

The Crosby plant makes and stores organic peroxides, a commercial product used to make plastics such as auto parts and Solo cups. But though it’s used in everyday objects, it’s a dangerous chemical when not stored at or around freezing. If inhaled, it can cause serious lung impairment or death, Doyle said.

“There’s no way to put the genie back in the bottle with this chemical,” he said.

During Harvey, employees moved the product through floodwaters and into refrigerated trailers, some of which eventually lost power and ignited, releasing toxins. Two deputies drove through a cloud of smoke, becoming sick. They, along with responding medical staff, reported vomiting and gasping for breath, according to a civil lawsuit the first responders filed against Arkema.

In its emergency response, the company misrepresented how closely it could remotely monitor the temperature of the hazardous materials, and failed to properly warn emergency responders, Doyle alleged.

Defense attorneys countered that Arkema officials shared all the company knew during the hurricane.

The trial almost imploded just hours after it began. Doyle’s opening statement set off an uproar among the defense attorneys, who called for a mistrial and stirred with anger as Doyle apologized for mistakenly telling jurors about awitness to whom he planned to grant immunity. Senior Judge Belinda Hill declined to declare amistrial and instead issued the prosecutor a warning for violating one of her previous orders.

“I feel like we are witnessing an opening argument of ‘My Cousin Vinny,’” Arkema attorney Rusty Hardin said, referencing the 1992 court comedy.

The trial continued, but the clamor on the first day gave jurors a sense of what’s to come in a case that has been rife with drama and surprise from the start. Prosecutors ran into trouble earlier this week when Hill ruled that they withheld or delayed the disclosure of evidence that was beneficial to the defense.

If convicted on the reckless emission charge, Arkema could face up to a $1 million fine, and Rowe and Comardelle could be sentenced to up to five years in prison. If convicted on the assault charge, Arkema could be ordered to pay a $10,000 fine, and Keough could be sentenced between two and 10 years in prison.

The trial is expected to last up to six weeks and will resume Monday, as a broken water pipe caused an emergency response elsewhere in the city and led the courthouse to be evacuated Thursday.