Homeless caught in Abbott’s fight with Austin

Governor orders TxDOT to clean up underpasses after camping ban eased

By Sarah Smith STAFF WRITER

AUSTIN — From all the times people have leaned out of their car windows to cuss her out, Gabriela Roque knows how she’s seen.

People have sworn at her when she washed car windows to get money or when she stood at Cesar Chavez Boulevard, holding a cardboard sign that said “hungry.” She’s gotten looks as people drive by or cross the street to avoid where she’s camped out.

Part of her understands. Even she looks sideways at the man who lives across from her who wears red-tinted glasses in the shape of lips and is so strung out on drugs that he talks to people who aren’t there. But she’s not like that.

Roque, 24, has lived under the Interstate 35 overpass in Austin for nearly a year, right by the capital’s famous Sixth Street corridor. She, like the other homeless in Austin, has been for the last four months caught up in the latest fight between Republican Gov. Greg Abbott and his state’s most liberal city.

It all started in June, when Austin relaxed its decades-old ordinance against camping. Abbott pounced, tweeting about crime, urine, feces and needles allegedly stemming from the change and threatening to use the power of the state to restore order. To Abbott, allowing camping only caused problems rather than solving them.

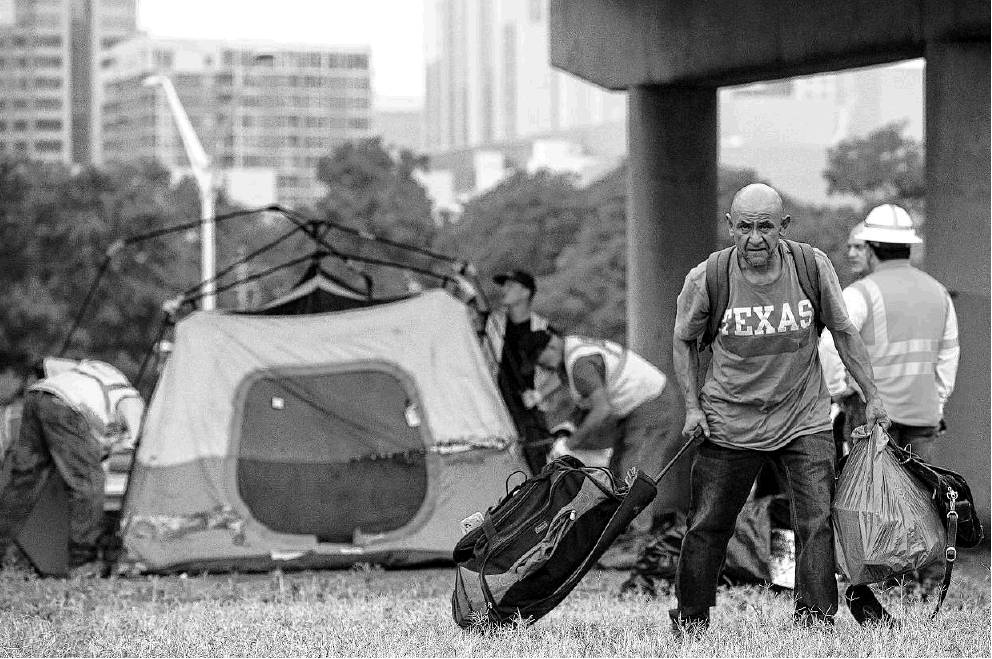

In the end, the governor’s only recourse was to bring in the Texas Department of Transportation to clean out under the bridges, where the state has right-of-way, beginning midday Monday. TxDOT will clean at least once a week. It’s work the city is already doing.

John Wittman, a spokesman for Abbott, said the cleanups were a “success.”

“This community, including those experiencing homelessness, deserves more than the city’s empty gestures,” Wittman said in an emailed statement.

Using the poor as political fodder is an old trope, from Ronald Reagan’s so-called “welfare queen” to President Donald Trump’s recent description of California cities “destroy(ing) themselves” with homelessness.

“They’re like, ‘We have got to find a stick to whip people up with,’” said Amy Price, communications and development director of Front Steps, a nonprofit which manages the Austin Resource Center for the Homeless (better known as the ARCH). “So it’s, ‘What if we blame homelessness on the liberals?’ ”

And many of the 1,169 unsheltered homeless in Austin feel the effects of the rhetoric. They said people look at them like “slime” and made them feel like “trash.” More than one person living on the street said all they really wanted was to be treated like a human.

“It makes me wanna go slap the governor and say, ‘Hey man, you gotta think about this,’” Roque said. “Here’s the question that needs to be asked more often: How are we supposed to get things done when they can’t make up their damn minds on what the hell they wanna do with the damn law?”

Twitter wars

Scroll through Abbott’s personal Twitter account and you’d be forgiven for thinking Austin has descended into a war zone.

Per Abbott’s Twitter, Austinites pick their way through piles of feces and needles. Crime runs amok. Among the offenses the governor showcased: A homeless man attacked a hapless commuter and threw a scooter through his car; a homeless person caused a two-car accident by running out into traffic; a man hit a car over and over with a metal pole twice his height.

Except Abbott’s accusations are either isolated incidents or incorrect. The two-car crash wasn’t the fault of a homeless man. The man slamming the metal pole into a car wasn’t living on the street, his family said. He was suffering from a severe mental illness. (Abbott has yet to apologize or remove the video.)

“At some point cities must start putting public safety & common sense first,” he wrote. “There are far better solutions for the homeless & citizens.”

But the statistics don’t back Abbott’s narrative. A note for council from Austin Public Health said that while “fecal matter has been found,” there is “not an increase in fecal matter.”

The crime statistics, presented in an Austin City Council meeting, note a 5 percent increase in property crime and a 6 percent increase in violent crime comparing the months after the camping ordinance was relaxed to the same time the year before. The highest jump in both categories, though, was crimes with homeless victims and non-homeless perpetrators.

Austin’s overall homeless population — 2,255 in 2019 — has ticked up slightly since 2017 after a steady decline since 2011. The unsheltered population, however, went up by just 33 people from 2018’s count. But lifting the anti-camping ordinance has made the unsheltered homeless more visible.

When Austin changed the ordinance, advocates said, it finally gave people a chance to breathe.

“It gave people the opportunity to breathe and be in one place,” said Chris Baker, who runs a nonprofit called The Other Ones Foundation. “How are you supposed to navigate yourself out of homelessness when every week or two weeks or every few days, some man with a badge and a gun and a stick is telling you you’re not allowed to exist where you’re staying?”

The Other Ones, which helps employ people experiencing homelessness, was initially under contract with TxDOT to help clean the encampments. The group pulled out, Baker said, once he realized what was going on.

Austin shelters are full. The people on the street know it, and so do the people who run the shelters. Price, who works at ARCH, said the Austin shelter system has about 1,200 beds — too few for the need. ARCH has a waitlist of about 200.

The flyers put up by the state around encampments listed ARCH as a resource. Nobody, Price said, consulted the shelter. She was furious. Anyone who comes to them will be on a waitlist.

“All this is eroding the trust those of us working with people experiencing homelessness are able to develop,” she said. “You just keep believing you need to show up when you’re asked for, because it all feels broken.”

‘People that need help’

By Monday morning, Raymond Thompson had moved his tent and possessions across the way from I-35 and Cesar Chavez. TxDOT, he had heard, was to come at 7:45 a.m., and he wanted to be ready.

That day they did not come at all.

Austin police told Thompson and his group they could not stay in the small grassy area across from the overpass, or they would be cited. So the group waited.

“All over there, it look like people that need help,” Thompson said, pointing to the underpass where chairs and sleeping bags lay abandoned by their owners. “People is not paying attention to that. They’re only paying attention to it because they’re dirty.”

Thompson has gray hair but he’s not sure how old he is. Nearly every other front tooth has a peeling gold grill.

The people on the street are his family. Thompson has struggled with homelessness since he was sent to prison in 1999 for assault. His mother, his emotional support, died when he was inside. In his words, losing his mother made him flip a little.

Thompson has dyslexia, bipolar, schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder. He still struggles with racing thoughts. He self-medicates with K2, the under-the-bridge street name for synthetic marijuana.

“It takes away the pain, it takes away the hurt, it takes away the loneliness,” he said. “It makes you feel: ‘I can go through this no matter what.’ I need something to balance me out.”

Three hours after the supposed Monday start time, Thompson and his friends rolled up their blankets, mats and sleeping bags and stuffed them into a blue tent.

Once, he had a job that paid $11 per hour. In high-rent Austin, he said, it wasn’t quite enough to get by (“Especially,” he added, “if you ain’t got the right color skin.”)

Across the way, one tent remained up. Aman had died there the week before. Police are awaiting autopsy results. Abbott tweeted about it as more evidence that Austin’s homelessness policy caused crime.

Thompson knew the man. He was agood friend, the kind who would give the last of what he had to someone else.

When TxDOT rolled through on Tuesday, making their way up I-35, the crews stopped at Ceasar Chavez, where Thompson and his family used to camp.

Crews went to clean up the tent of Thompson’s dead friend. He and two friends ran over to get the dead man’s possessions. He salvaged a blue-covered Quran — tucked in his back pocket — a beat-up football, a duffel. He filled a suitcase with his friend’s belongings and took what he could, along with a blue bike, back across the street.

There, with his family and his pit bull mix named Debo, he waited.

To Thompson, the cleanup isn’t any way to deal with homelessness. The homeless, he said, need housing, mental health care and sessions for life skills on how to get on their feet.

All this does is remind him how people see him.

“They see waste. They see trash. They see slime,” he said. “A person just drives by and you can see it in a glance — a little glance that can really tear a person down.”

‘Expecting … empathy’

For all the anticipation around the state cleanup, it was the Monday clean-out initiated by the city of Austin that brought the most drama.

Police towed a minivan that they thought belonged to one of the clients at the ARCH shelter (the front desk had no idea whose it could be). Mattresses, chairs and tarps were tossed in a dumpster. Sticking out, wedged between a dirty mattress and the side of the dumpster, was a hand-painted sign: “Where will I Sleep?”

“Caseworkers are not gonna come to the woods!” one man in a black puffer shouted. “Caseworkers are not gonna come to the woods!”

As homeless people in the highway encampments waited for TxDOT to descend on Monday, the city of Austin had begun a cleanup of its own. This cleanup began around the middle of the day, after TxDOT had said it was going to start but before the state actually began.

In mid-October, Austin City Council had reinstated part of the ordinance: There was no camping within 15 feet of a residence or building during operating hours, or near the ARCH. It was the block across from the ARCH — which had quickly become lined with tents — that presented the problem.

Police returned to the block outside the ARCH at 4 a.m. Tuesday morning to finish the clear-out. To the people camped outside, it looked like the police had picked a time when they could avoid crowds and cameras. An Austin Police Department spokesman said in an email that the department decided on the early morning cleanup because the crowds Monday made a full cleanup unsafe and they were better able to close the street.

Austin police will conduct daily patrols in the area.

“They passed a law that people could tent out here. Then you go back on your word,” said Kendall Cook, 48, outfitted in a Longhorn puffer and a black-and-blue felt hat. He lost his apartment when he went to jail and has been homeless on and off for the past three years. Sometimes, he wonders what the point of jail and rehabilitation was if he gets out and can’t even get into most apartments or jobs.

“I’m a plumber. I live out here on the streets — as a plumber,” he said. “That’s madness.”

The prevailing rumor outside the ARCH was that they would have to move to the woods — where, Cook said, there’s no safety like there was in the community tenting across from the ARCH.

Just down the block from where Cook paced, Dalzell Waldrop sat in solidarity with three of her friends who were about to be moved. Waldrop, 57, has stayed at the Salvation Army since she was released from a psychiatric hospital. She hopes she won’t get kicked out for being with her friends.

Waldrop had gone to one City Council meeting about the homelessness issue with her friends. They clapped for themselves, she said. Nobody else would.

“I went in expecting to see empathy,” she said. “I heard the bad stories.”

Her friend Sherry Hughes, sitting next to her with neon-green sunglasses, nodded. She slept outside the ARCH for safety. She has no idea where she’s going next.

“I’m a Texan, born and raised,” she said. “I’m a Texan. Not trash.”

Nowhere else to go

By the end of Tuesday, Gabriela Roque’s mattress would be thrown away and her orange-and-grey tent would be dismantled, loaded into The Other Ones’ minivan and put in one of the group’s temporary storage units.

But she planned on waiting out the cleanup and coming back. She had nowhere else to go.

On Monday, the promised day of cleanups, nothing happened where Roque lived. Roque and her boyfriend had to decide between staying with their things and getting lunch. They chose lunch.

On Dec. 22, Roque mark her first anniversary of living on the streets. She hates it.

“You get to relax and have a warm spot for the night, you don’t have to worry about your next meal,” she said. “As far as us out here, if it weren’t for two places feeding us one time a day, we probably wouldn’t have nothing to eat out here.”

Some days they have enough for two four-for-$4 meals at Wendy’s. Thanks to a cooler they found, they can store up the sandwiches and TV-dinner meals church groups and do-gooders bring.

When Roque moved out to the street, she was detoxing from a bout of shooting heroin and meth. She wanted to get sober for her son, whose first word was “mama.” He’s turning 7 in February, and she hasn’t seen him since he was 4. But four days after becoming homeless, she got depressed and relapsed. She’s off most of the hard stuff now.

She’s got some family in Austin. They won’t take her, she said, after her addiction and her mood swings.

“We’re reaching out for help but ain’t nobody wanting to help us with a damn thing,” she said. “One of my caseworkers left, and they told me who else to get in contact with. The only way to make an appointment is if I email her or call her. Hello- o, it’d be nice if I had a phone.”

Her boyfriend, 40-year-old Jason Butler, is all for removing the downtown campers. It’s too much clutter, he said. Roque is inclined to agree. She’s angry at everyone who’s complaining now and didn’t keep their area neat. What, she wonders, did they expect?

But the back-and-forth is exhausting.

“We have nowhere else … to go,” she said. “They really don’t want us on the damn street? All these … buildings they’re building, why don’t they use some of those available open spaces and build a building like a motel?”

She sighed.

“I wish I could run for office,” she said. “It kinda makes me want to run.” sarah.smith@chron.com

“I’m a Texan, born and raised. I’m a Texan. Not trash.”

Sherry Hughes, a homeless person in Austin