MEDIA

I worry about the stories the Chronicle can no longer cover

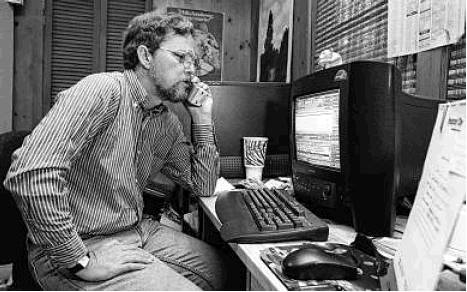

By Mike Snyder

My phone beeped. Immersed in a story I was editing, I ignored it. It beeped again. Then again.

Finally off deadline, I picked up the device and saw a series of text messages from an elected official in a community where I had done some reporting a few years ago, before I was reassigned to editing duties. Some sketchy stuff was going on, he wrote, and no one was paying attention. Please pay attention!

I’ve seen this movie before. In the absence of vigilant coverage, local officials come to believe they can misbehave with impunity, and often they’re right.

I assigned a reporter to dig into the matters my caller was concerned about, but I knew that this would be, at best, a temporary solution. More coverage gaps are inevitable in the vast, news-dense greater Houston area. Our staff, reduced to perhaps half the size of 15 years ago, is stretched thin. Every day, we engage in a sort of journalistic triage: cover this, skip that.

After more than 40 years at the Chronicle, and 43 years of writing and editing for daily newspapers, I’m preparing to retire. The worried tone in my caller’s voice nags at me.

The industry landscape was much different in January 1979, when I first set foot in the Chronicle newsroom. So was the room itself: It was full of smoke, for one thing, and far noisier than the librarylike environment where my colleagues and I now work. Reporters shouted “Copy,” just like in the movies, summoning young clerks known as “copy kids” to run errands. Paste pots, pica poles (fancy rulers) and proportion wheels (don’t ask) sat on copy editors’ desks. Pneumatic tubes — cutting-edge tech! — whisked hard copy to production departments on another floor and returned with page proofs to be examined for typos.

People yelled and swore a lot. The city editor once threw a phone book — the residence pages, as I recall, much thicker than the business directory — at a reporter. I never saw any bottles of gin concealed in desk drawers, but it was not uncommon to enjoy a cocktail or two with lunch. If anyone ever went to the gym after work, they didn’t talk about it.

One of the first people I met was Lynwood Abram, a rewrite specialist whose job was to compose stories based on notes dictated by reporters in the field. Some friends from college who worked at the Chronicle had informed me of Abram’s astounding ability to turn the disjointed words and phrases of harried reporters barking into pay phones into coherent, even elegant, prose — on deadline. I was in awe. (My threshold for awe was lower at 24).

“What does it take to be a great rewrite man?” I asked Abram earnestly as we shook hands.

He gave this question the careful consideration it deserved — maybe two seconds — before replying: “Just lucky, I guess.” Over time we became fast friends; he died in 2015.

Over the years, the paper changed gradually, and then it changed dramatically.

The Chronicle, following the industry trend, switched from afternoon to morning publication in the early 1980s. The Hearst Corp. bought the paper from the Houston Endowment for $400 million in 1987. Our chief competitor, the Houston Post, folded in 1995, costing many fine journalists their jobs and depriving the city of an important voice. That same year, the Chronicle’s website blinked to life, and readers for the first time could read our work on computer screens. It seemed like an amusing novelty.

My role at the paper varied over the years, but Ispent my entire career covering local news. As a result, trips on the company dime have been rare; I went to San Francisco once for a story, which was cool, and I covered a1986 mass shooting at a post office in Edmond, Okla., which was not. I’ve never covered a national political convention, a presidential inauguration or a war.

There is, though, a distinct satisfaction in writing or editing stories that affect the lives of people you might bump into in the grocery store. After Hurricane Ike struck Galveston in 2008, I spent months driving my old Saturn around Galveston Bay communities such as Shoreacres and El Lago, talking to people struggling to recover and trying to hold accountable the government agencies tasked with helping them. These families deserved to have their stories told, and no one else was telling them.

Covering local stories involves many hours of sitting through dull meetings or plowing through stacks of documents, but once in a while, something exciting happens. I once got a scoop from asource during a covert meeting in a parking garage, just like another reporter you may have heard of. Bob Woodward’s source helped him topple a corrupt president; mine told me about plans for changes in Houston’s civil service rules. I like to tell myself the difference is mainly one of context.

Local news, as it happens, is the realm that’s been hardest hit by the recent industry struggles. Big national papers such as the New York Times can generate revenue from a vast market of potential subscribers, but few people in, say, Des Moines, Iowa, would pay to read the Houston Chronicle. This was not a concern in the years when a robust supply of display and classified ads kept the paper fat and happy, but now it’s an existential crisis.

The effects are not limited to news organizations and their employees. “Recent academic studies show that newspaper closures and declining coverage of state and local government in general have led to more partisan polarization, fewer candidates running for office, higher municipal borrowing costs and increased pollution,” Governing magazine reported in April.

Not long afterward, Governing succumbed to the very forces it had written about, telling readers on its website that its continued publication was “unsustainable in today’s media environment.”

Even in its diminished state, the Chronicle in recent years has produced some of its best work in decades — perhaps ever. This didn’t happen by accident. Complacency is no longer an option. The stakes are too high.

The Chronicle is in a stronger position than many of its industry peers, with supportive owners, a talented staff and committed newsroom leaders focused on luring more online subscribers with good journalism. The next few years will be critical. If you don’t think the work we produce is worth paying for, consider what might happen if no editor was listening when the phone beeped with a news tip. Imagine a community without independent oversight of local government, business, nonprofits and other institutions.

It’s not a pretty prospect. We all deserve better.

Snyder retired from the Houston Chronicle on Friday.