Flood-fatigued ask: Is Houston worth it?

Another ‘500-year’ event adds to heavy psychological toll

By Maggie Gordon STAFF WRITER

As the flood-weary city of Houston recovers from yet another historic storm in the coming days, rubber-gloved mucking brigades and tow truck armies will swoop in to clean up the physical mess. But more and more, Houstonians are finding that the toll of these repeated floods reaches far beyond the physical. The events have changed the very way our city feels.

A Rice University study published earlier this month found that nearly 20 percent of flood victims surveyed in the wake of Hurricane Harvey reported post-flood PTSD, depression and anxiety. And more than 70 percent said the prospect of future flood events was a source of worry.

Harvey was the third “500-year” rain event to hit Southeast Texas in three years. This week, Tropical Storm Imelda also earned that distinction, as some areas received more than 40 inches of rain, paralyzing the area as highways morphed into parking lots and first responders performed more than 2,000 rescues Thursday alone. And many residents are now asking themselves: Is Houston worth it?

A week ago, Amber Ambrose knew the answer to that: A yes so resounding that she and her husband put an offer in on a new house. Come Thursday night, the couple — who rebuilt their first home after it was flooded in the April 2016 Tax Day floods, and again after it was flooded in Harvey — were contemplating pulling their offer.

“It’s frustration. Exhaustion. A feeling that there’s a formula to these things,” Ambrose said. “It comes up. We know it’s going to be bad. It ends up being bad. And then we have all these stories of people helping each other out. And it’s the same story that plays out every freaking time. And I’m heartened by that — how we’re always kinder to each other in these situations. But can’t we find another way to be kinder? Does it have to be a flood every year?”

The flood waters recede, and we go back to hoping it never happens again. But then, of course, it does.

“It feels like the definition of insanity,” she said.

Still, after a lot of back and forth, and with a day left on the deadline to decide whether to pull their offer, Ambrose and her husband chose to buy the house in Oak Forest, a less flood-prone part of the city. With one condition: “This is afive-year plan. We’re going to move in five years,” Ambrose said.

That decision doesn’t come easily. Her family has grown up with this city. Her oldest daughter is the same age as Discovery Green, her youngest nearly the same as the walking trails at Buffalo Bayou Park. They’ve watched Houston blossom since they first moved in nearly 13 years ago. Ambrose doesn’t want to give up on Houston. But she feels like she needs to.

“I’m not a scientist,” she said. “But it feels like Harvey is the new norm. It’s going to keep happening.”

And it’s getting too hard for her to keep living through.

‘Emotionally draining’

Ronald Acierno, director of UTHealth’s Trauma and Resilience Center, compares the cumulative effect of Houston’s weather events to a combat veteran who experienced improvised explosive devices in crowded marketplaces.

“Just as they may experience stress just being in a busy shopping center, new flooding can elicit anxiety or panic in victims of previous flooding,” said Acierno. “Even if they’re not affected by the new flooding or the danger isn’t as intense, the similarity will trigger a response.”

Acierno said “emotionally draining” is a good term for the frequent flooding’s effect on those for whom the toll doesn’t constitute PTSD.

“We don’t need to pathologize normal responses,” said Acierno, a professor of psychology at Mc-Govern Medical School at UTHealth. “That doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt.”

Acierno said seeking treatment or connecting with other people going through the same experience is the most protective way people can deal with the constant stress.

It is this connection that is urging other Houstonians to dig their heels in on this city. On Thursday afternoon, Amanda Sorena alternated between checking her phone constantly for new text messages from her neighbors in Meyerland to checking the gauges to ensure her home wouldn’t flood — again.

“It’s nerve-wracking. You’re playing the game of trying to figure out where to stay safe, and how to remain calm and be present of mind the whole time,” she said. “You’re figuring out your plans again. Is this a situation where I need to pick stuff up off the ground? Or will that just make me more anxious?”

She went out back and began pushing water around her yard. She texted her children’s teachers. She made a mental inventory list of the supplies she had on hand: gloves, bleach, contractor bags. Mostly she kept herself busy.

“I don’t remember being like this pre-Harvey,” she said.

But she also doesn’t remember feeling as closely tied to her neighborhood, or neighbors.

“I have for sure had the conversation with myself: Should we stay here? But our community runs so deep,” she said. “Our roots in our community are so much deeper after these storms, because we all come out and help each other.”

The Rice survey found that 62 percent of flood victims want to stay where they live, many citing “emotional attachment to the neighborhood” as a fundamental reason.

Still, that doesn’t make it easy.

Katie Sullivan was high and dry — up in a second-floor garage apartment in Montrose — on Thursday. She knew she’d be safe. Yet she “stress ate” her way through a large container of milk chocolate sea salt caramels as she pinballed to her window and back, constantly checking her car. “Should I move it?” she kept asking herself. “Would it be safer down the street?”

She couldn’t find a perfect answer.

“There’s nothing you can do. You’re powerless,” she said. “You have no control over where the storm will go.”

‘Here we go again’

And this storm was particularly hard to track and predict, said Matt Lanza, a meteorologist who runs the Space City Weather blog along with Eric Berger. The models were calm nearly all the way through last weekend. Then, on Sunday, one weather model predicted a storm that could unleash up to 25 inches of rain. The quantity remained the same. But the bull’s-eye kept bouncing.

Lanza couldn’t figure out where this would land. So he kept checking the models, running and re-running scenarios.

“There’s this sense of disbelief when you see something like this. You have to come to the reality of, is this really real? And the answer every time it happens in the last few years is yes,” he said. “And it’s ‘Here we go again.’ ”

Some people who have never experienced flooding experienced it during Imelda. Others who have seen the brunt of Harvey were spared. There was no rhyme. No reason.

“Every flood in Houston is unique. It doesn’t matter if you get 5 inches of rain or 45. It depends on where it fills, how fast, what the conditions were like prior to when it fell, and any other combination of things,” said Lanza. “You could flood even if you never flooded in Harvey or something worse than Harvey. Even if it’s just a freak storm like (Thursday). And that’s one of those realities people have to accept when they live here.”

For Lanza, it’s still hard to accept. A native of New Jersey, he’s lived in Houston since 2012. And while he sometimes wonders whether the city is worth it, his chosen profession makes this corner of Texas anever-ending rush. It’s an honor to report the weather here, he said.

But he understands why others might ask the existential questions about whether it makes sense to remain in a part of the country that tries to wash you away once ayear.

And for people who have flooded before, each additional flood can make things infinitely worse, said Dr. Asim Shah, a Baylor College of Medicine psychiatrist.

“It’s been one event after another after,” said Shah, vice chairman for community psychiatry at Baylor. “Collectively, it increases the stress, the anxiety, the panic.”

Shah said studies after Hurricane Katrina have shown subsequent trauma causes extreme depression and symptoms take a long time to resolve in those most affected by the original disaster.

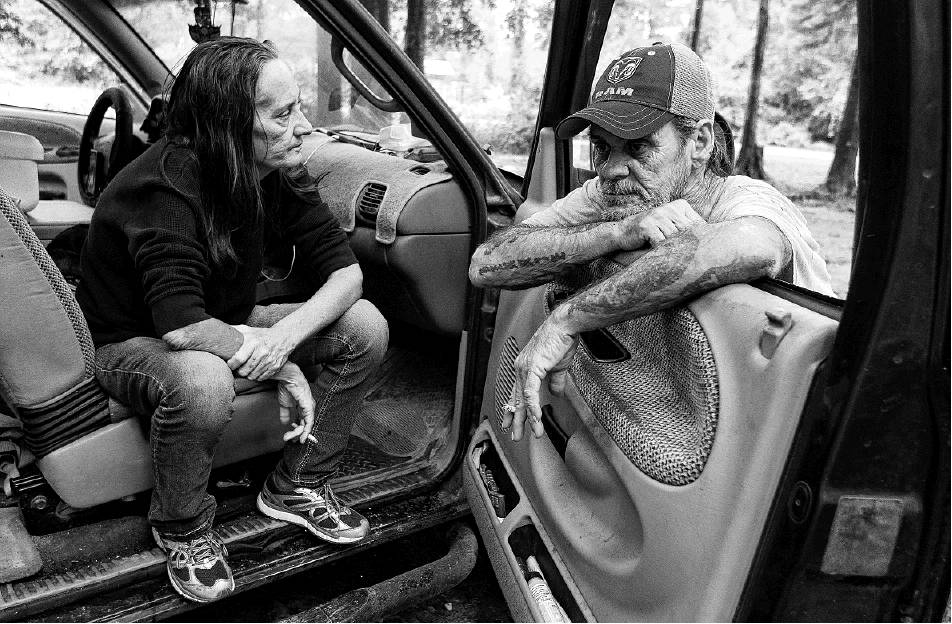

Marie Perkins wasn’t thinking about the effect of compounding trauma early Friday morning as she was rescued by boat from her Huffman home. She was hoping she’d survive. And wondering how she could prevent ever having to live through this terror again.

“What do you move to that doesn’t flood anymore?” she asked.

Unlike some neighbors who said they were prepared to rebuild, Perkins didn’t know if she was going to stick around to see another flood happen.

“I don’t know yet,” she said. “I love my house, but I can’t do this again. I definitely cannot do this again.”

Todd Ackerman and Brooke

Lewis contributed to this report. maggie.gordon@chron.com twitter.com/MagEGordon