TRANSPORTATION

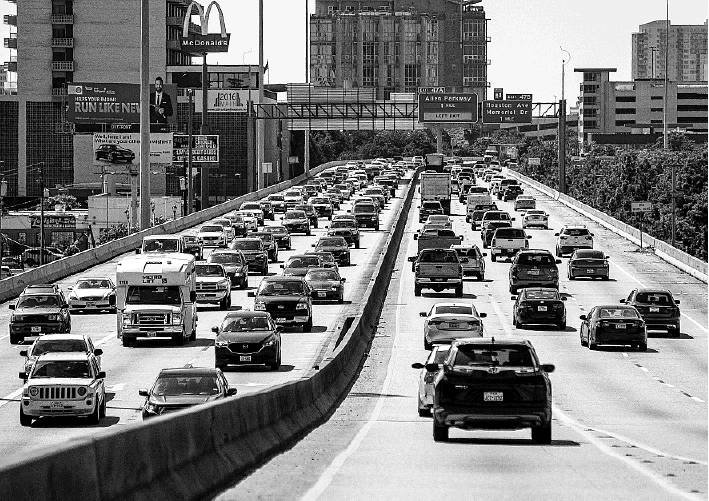

HOUSTON, STOP THE I-45 EXPANSION

IT WILL DO THE CITY VASTLY MORE HARM THAN GOOD

By Jeff Speck

This past February, when I arrived to give a lecture in Houston, I was met by protesters holding signs. This had never happened to me before. Happily, it turns out we were on the same side: They had come to the MATCH Theater for the same reason I had, to stop the ill-conceived $7 billion expansion of Interstate 45 through the city. Their motivation was mostly personal: a desire not to have their homes destroyed, their air polluted, and their tax dollars wasted. Mine was more professional: the hope of helping a major metropolis to make itself better. While my lecture was kindly received, it was far from decisive, so my campaign continues here today.

The planned expansion of I-45, as it is being perpetrated upon Houston by the Texas Department of Transportation, can be described as having significant costs and significant benefits. The costs are best understood as tremendous, and the benefits are best understood as false. How this can be the case — why the full-speed-ahead reconstruction of Houston’s central automotive artery needs to be reconceptualized as amassive investment in making Houston worse — is a story that needs public airing.

Lost homes, businesses, revenue, and community

Seven billion dollars is the low end of what TxDOT describes as the likely cost for this project, which has been sold as a highway improvement but is more accurately a highway expansion: It adds four to eight lanes just about everywhere along its length, and as many as 13 new lanes in some places. By TxDOT’s own admission, this expansion will destroy no less than 1,235 units of housing, home to about 5,000 people. These people may not land on their feet: The citizens I met in the Delaney Street Homes worry that TxDOT’s version of “fair market value” will not allow them to afford houses of similar quality nearby.

The expanded highway also will plow through 331 existing businesses providing almost 25,000 permanent jobs. Together, these residential and business losses are predicted to cost Houston about $135 million in forgone city property and sales taxes each year.

But these financial deficits pale next to the very real human cost of breaking communities apart. This cost is well documented in books like Robert Caro’s “The Power Broker ,” one of those stories you read while thinking, “well this could never happen today.” But it is about to happen in Houston. Forty percent of the young students at Bruce Elementary will lose their homes and end up at different schools. The historic Greater Mount Olive Baptist Church, the heart of Independence Heights, will be demolished, along with 43 other properties there. Remarkably — and, one hopes, illegally — the first town incorporated by African Americans in Texas was completely omitted from TxDOT’s Historical Resources Survey for this project.

Decreased competitiveness

Houston has a lot going for it, but it is consistently ranked quite badly in competitiveness metrics like the Mercer Quality of Life Index. In the most recent ranking, Houston came in 66th , tied with Los Angeles and Miami and just behind Dallas and Atlanta. Only four American cities included on the list did worse. Which cities did best? San Francisco, New York, Seattle, Chicago and other places with walkable downtowns, good transit systems and considerably fewer highway lane miles per capita. The international winners, like Vienna, Zurich and Vancouver, have nothing resembling a freeway anywhere near their downtowns.

Meanwhile, Houston has more freeway miles per capita than every large city except Kansas City and St. Louis. This is no coincidence. St. Louis is 70th in the Mercer Survey. Kansas City did not qualify.

History has shown that investments in highway systems can potentially benefit a region, but they never benefit the center city. In fact, highway investments benefit surrounding municipalities precisely at the expense of city centers, which end up actively subsidizing their growth. Moreover, urban highways, once hoped to uplift downtowns by improving access, ended up undermining downtowns by encouraging dispersal. This phenomenon was well described by Rochester city engineer James Macintosh: “We built an evacuation route. It worked: Everybody evacuated.” That city is now removing its Inner Loop highway.

The false benefits

TxDOT cites three principal motivations for advancing the I-45 project: reducing traffic congestion, improving driver safety, and improving air quality. These laudable goals are apparently considered important enough to outweigh the significant costs discussed above. And they might be — if they were achievable.

Sadly, each one is a false promise. Decades of similar state projects around the U.S., each with its own ample justification, teach a simple lesson: highway widenings do not reduce congestion in the long run, and make they both driver safety and air quality worse.

The fundamental law of highway congestion

Well-documented by study after study, the “fundamental law” of highway congestion tells us that when you expand congested freeways, they quickly become re-congested with a greater volume of traffic. The phenomenon is called “induced demand.” Because the principal constraint to driving is congestion, removing that congestion induces more people to drive during rush hour, generating yet more traffic. The data tell us that every new mile of roadway that you build will typically be 40 percent filled up with new drivers immediately and 100 percent full within four years.

In city after city, congestion is the constant. In one 30-year study, the Texas Transportation Institute found that those cities that invested heavily in new roads experienced no less congestion than those that did not.

It is ironic to be having this conversation in Houston, because Houston already owns the international poster child for induced demand, the Katy Freeway. With federal help, TxDOT paid $2.8 billion turning the Katy Freeway into “the world’s widest highway” in order to reduce congestion. Within four years of completion, the morning commute was taking 30 percent longer, and the afternoon commute was taking 55 percent longer than before construction.

Transportation planners around the globe have heard this sad story. Transportation planners outside of Houston have actually learned from it.

Micro safety vs. macro safety

When a highway widening project includes the elimination of certain local hazards, such as tight turns and short on-ramps, it is typically billed as a highway safety project. This can be correct on the micro scale, since fixing these problems can reduce the number of crashes on those specific segments.

At the macro level, however, a different logic prevails, in two ways. First, one explicit goal of the project is to increase highway speeds. TxDOT’s engineers predict that a rebuilt I-45 will increase traffic speeds by a full 24 mph across downtown. The single greatest predictor of a death in a car crash is vehicle speed. While removing local hazards may reduce crashes, higher speeds systemwide can be expected to cause a net increase in injury and death.

But to fully understand the macro scale, we need to step back and compare Houston to other cities that have grown differently.

As mentioned, Houston already has more miles of highway lanes per capita than almost any other large American city. Getting around Houston invariably means spending a lot of time speeding along freeways and on their treacherous feeder roads. Predictably, Houston has one of the higher driving death rates in the U.S., more than double that of less highway-based cities like Boston, Chicago and San Francisco.

So, what happens when Houston expands its highway capacity and becomes even more of a highway city? The data suggest that any lives saved by fixing a few problem areas are likely to be no more than a rounding error on the lives lost due to increased fast driving citywide.

Air quality impacts

Finally, TxDOT’s public materials trumpet — in green print, no less — how widening I-45 represents a “potential major air quality improvement for the region.” This prediction, that reduced congestion will reduce vehicle emissions, defies all experience. The simple fact is that increased highway capacity universally results in increased vehicle emissions. More lanes mean more cars, and more cars mean more pollution.

Of the 10 largest American cities, Houston burns the most fuel per capita. A Houstonian who moves to Chicago cuts her tailpipe emissions by 35 percent. Of these cities, Houston already has the most highway lanes per capita. If there is an award for becoming worst on climate, TxDOT is chasing it.

Houston is ranked ninth in the U.S. for ozone pollution, and has never met national standards for ozone emissions. A recent study found that roughly 25 percent of Houston families with children ages 5 to 17 have sought help for asthma in the past few months. For black families, that number rises to 45 percent. The majority of unhealthy air emissions in Houston come from the transportation sector, and recent studies show that the worst health impacts from transportation occur within 500 meters of highways.

What a wider I-45 means for this sorry situation is obvious. A dozen day care facilities and two dozen schools sit within a mere 150 meters of the highway. More cars and trucks, at any speed, means more particulate matter, more asthma, and more environmental inequity for Houston.

Two futures

If I-45 is widened, it will be remembered that, in the decade prior, Houston enjoyed abrief glimpse of a better future. Downtown and Midtown have been reborn, lifted on a demographic shift that favors urban living. Regional bike trails grace the Bayou Greenways, and a brilliant Beyond the Bayous plan lays out an ambitious path for sustainable growth. Transit ridership is up, thanks to investment in light rail and a redesigned bus network. The mayor, members of City Council, and county commissioners all sing the praises of amore walkable Houston. Sadly, all these trends will be reversed if Houston doubles down on its nation-leading commitment to fossil-fuel infrastructure.

This need not happen. Houston has the ability to stop the I-45 expansion in its tracks, just as Dallas stopped the Trinity Parkway. That proposed roadway was called “the worst boondoggle imaginable” despite costing only one-fifth of the current I-45 plan. It took a 10-year fight, but the good people of Dallas rose up and killed it.

Meanwhile, Houston’s fatalistic response to its TxDOT incursion has been to just “make I-45 better.” The well-resourced but cautious Make I-45 Better Coalition has proposed a collection of modifications, all good, that unfortunately do not begin to question the underlying folly of fighting congestion, car crashes and tailpipe emissions by welcoming more driving.

Here’s how to make I-45 better: First, fix the parts that need repair, without making them any wider. At the same time, introduce congestion-based pricing on the entire roadway to maximize its capacity around the clock. Invest the proceeds in transit, biking, walking and in those poor people who truly have no choice but to keep driving.

Unlike highway widenings, congestion-based pricing reduces traffic, driving deaths and pollution, all while earning billions rather than wasting them. It has worked wherever it’s been tried, including London, Stockholm and Sydney, and it is about to become law in New York City. Even Dallas has been experimenting with congestion-based pricing for years.

Introducing New-York-style strategies in a place like Houston is a heavy lift, but it’s important to start somewhere. That somewhere, for now, should be the immediate end of all city cooperation with this plan to make Houston worse. The data are so clear, the evidence from other cities — and from Houston itself — so great, that there is no other intelligent course of action. It’s time to put the brakes on I-45.

Speck is a city planner and the author of several books including “Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time.”