IN WEST TEXAS COUNTY, A ‘SANCTUARY’ FOR GUNS

Citing ‘brutal attacks’ on the right to bear arms, trio pushes plan — and stands by it after El Paso mass shooting

By Emily Foxhall STAFF WRITER

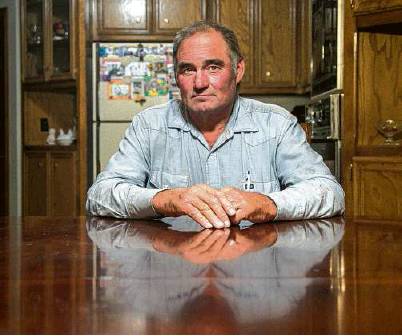

MARFA —Bill Applegate, who traps livestock predators in far West Texas, had never been involved in local politics before he learned about a grassroots gun rights movement spreading in America. Now he was in the Presidio County courthouse trying to see the idea through.

Applegate, 59, wanted to make this Democrat-dominated county on the border with Mexico a “Second Amendment sanctuary,” asymbolic designation that riffs on “sanctuary cities,” where local officials don’t cooperate with immigration enforcement. He hoped the vote would send politicians a pointed message: Don’t infringe on our right to bear arms.

Mass shootings in California, Texas and Ohio weeks later would horrify the nation. Impassioned calls would follow for tighter gun control to stop mass shootings that seem to claim innocent lives more and more frequently. But these tragedies would not change the core of Applegate’s thinking.

Applegate and like-minded Americans do not believe more gun regulation will help. They think criminals will always find ways to get firearms, while lawful gun owners jump through the hoops. Some argue that too many restrictions are in place already.

It’s apractical issue for these West Texans, but it’s also rooted in principle: They are used to having guns. They believe in their right to them, without caveat.

They see the political rhetoric that follows shootings — pushes for better background checks, magazine size limits and assault rifle bans — as a threat to these principles. Some deeply fear that the government will take their firearms, that they will have to fight back.

That day in the courthouse, July 10, ranchers stood shoulder to shoulder to argue for the sanctuary status during a Commissioners Court meeting. Already, the label had been adopted in parts of Illinois and in the nearby Texas county of Hudspeth.

Applegate and his allies had some convincing to do. At least one commissioner supported some gun reform. And County Judge Cinderela Guevara was worried that commissioners might overstep their role.

For Applegate, the issue felt personal, like the family photos that fill a kitchen wall at his home on the edge of Marfa. Or the razor wire that tops the chain-link fence.

He launched into a heartfelt speech: “The Second Amendment to our Constitution is suffering brutal attacks nationwide, and when we fail to defend and maintain our rights, those rights will crumble in our hands and slip through our fingers.”

Trey Gerfers, 49, waited in the chambers to discuss water issues. All of these comments saddened him. Something in America, he thought, was working people into a frenzy. Gerfers didn’t think anyone wanted to take guns from ranchers.

Everyone around him, it seemed, disagreed. He had never seen the courtroom so packed.

Red among blue

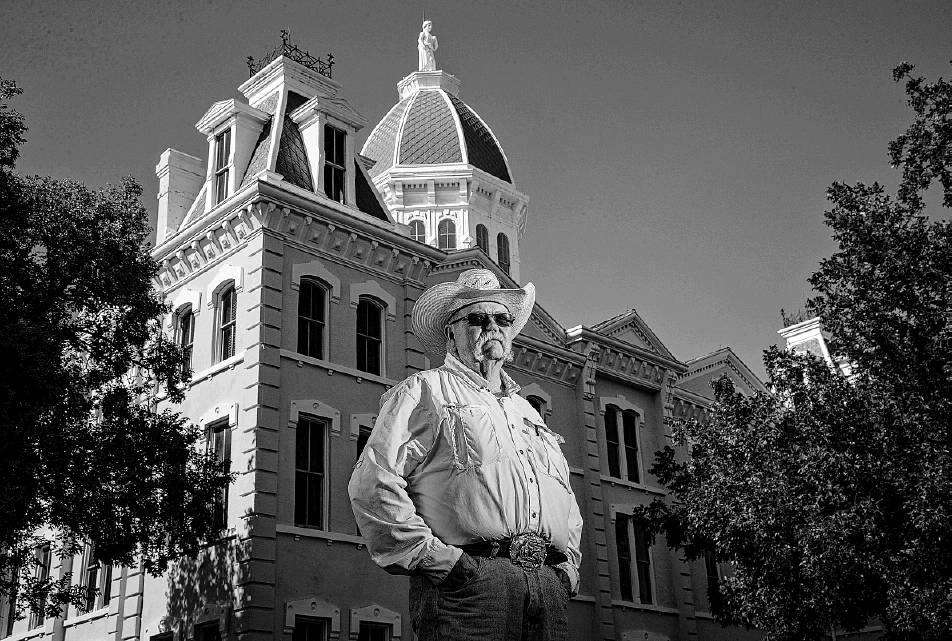

Gregory Romeu, 64, a Marine veteran, kicked off the discussion. He helped Applegate get the resolution to this point. Where Applegate is reserved, Romeu is aggressive, staunchly committed to protecting his idea of what the country is meant to be.

As Romeu sees it, America won its independence with guns. The federal bump stock ban upset him. He is among those who talk of a second revolution if Congress continues to overstep its bounds.

He lives in a16-foot trailer on 40 acres near the border, where he watches for immigrants with night-vision equipment .

This resolution was “a silent shot across the bow to the federal government,” Romeu told the judge and county commissioners, his voice reverberating in gravelly tones. It was awarning to politicians in Washington, D.C., to leave people in Presidio County alone.

“There’s plenty other states, plenty other counties that are weak-minded,” he said, “and don’t understand duty, spirit and liberty.”

Presidio County didn’t seem like aplace this would pass easily. The local Republican Party, which united Romeu and Apple-gate, until recently was all but dead. Here was the “last bastion of conservative Democrats,” Justice of the Peace David Beebe said.

Marfa, the county seat where they gathered, was adusty cow town turned art mecca, where hipsters and tourists rule, and cowboys and ranchers seem to visitors like part of the background.

But perhaps it was just that change — that sense their way of life was disappearing — propelling this resolution.

Rachel Mellard, a rancher and mother of five, told commissioners she always has a gun on hand.

“It’s been our constitutional right for years and years,” she said, “and it’s something that many of us still stand behind and do not feel that we would back down (from), whether y’all pass this or not.”

Way of life

Thomas Allen Rawls, 64, who goes by Tar, a third organizer in this effort, most days is out managing the remote ranch land south of Marfa where he grew up.

He checks on a fencing project. He taps tanks with a 6-iron to listen for how much water is in them. He guns his Polaris General, a utility vehicle, past ocotillos on rocky paths with a Smith & Wesson AR-15-style rifle in the back.

Rawls drinks green shakes and eats organic. He might shoot aferal hog or coyote, but here, where dust dries the throat and sun bakes the skin, his gun mostly gets dirty. The point is that he has it.

His wife, Nancy, has one too. She shared at the meeting about finding three unauthorized immigrants outside their house. They hear stories of immigrants raping and killing. Law enforcement was at least 45 minutes away.

“I hope never to have to use my gun,” she said. “But it’s no longer an option in my life. It’s become a necessity.”

Rob Crowley, 60, cramped, left the stifling room. He works in event production and does not have a gun but respected the right to it. He hadn’t known this issue was on the agenda.

Embarrassed and ashamed, he thought the resolution set a dangerous tone. But he planned to let it go as a foolish idea in a small town.

Others had no idea the proceedings were happening.

The county judge asked if anyone wanted to speak against the proposal.

No one stepped forward.

‘Under threat’

Commissioner Brenda Bentley was conflicted. She told the crowd she believed in age restrictions, magazine size limits and background checks for gun purchasers

“I do believe that those things are important,” she said, “because then the wrong people aren’t applying for these firearms.”

Applegate did not want to lose his momentum. He hurried to summon County Attorney Rod Ponton, who was upstairs for district court. Ponton saw nothing illegal about the document.

It was a “declaration of the state of mind of Presidio County,” he said, with no legal effect.

Ponton told commissioners they could do what they wanted. With a gun collection himself, he supported the effort. He thought it reflected the frontier spirit.

Commissioner Frank Knight, known as Buddy, thought this was going to be “hell on wheels” to pass. He moved to adopt it.

“I’m a Second Amendment guy,” Knight, who sports a horseshoe mustache and a shining belt buckle, said in an interview. “I think it’s been under threat quite a bit.”

Applause and whistles erupted. Guevara, the county judge, began to sway.

“We are under threat,” she said. “ You can see it. You can see it if you watch the news, if you read the newspapers. Our freedoms are threatened.”

They struck contentious language. Knight motioned to pass the new draft. “And Isecond!” the judge said.

‘Pointless and wrong’

Twenty-two people died three weeks later, on Aug. 3, in the El Paso Walmart, 188 miles from the Marfa courthouse. Texas Democrats called for new gun control policies. President Donald Trump tweeted that “strong background checks” should be enacted.

The three resolution organizers had varied opinions: Rawls conceded high-capacity magazines weren’t needed. Romeu thinks people should learn to use guns. Applegate believes criminals should be better punished.

They stood by their resolution, news of which was trickling out. The Big Bend Sentinel covered it locally. Alice Tripp, of the Texas State Rifle Association, affiliated with the National Rifle Association, was delighted to see them take a stand.

Their stance echos talking points from the NRA, which, according to its chief executive officer, Wayne LaPierre, “opposes any legislation that unfairly infringes upon the rights of law-abiding citizens.”

Gyl Switzer, executive director of Texas Gun Sense, felt sad. She longed for discussion of when guns were appropriate in whose hands. “There are ways to keep us safe that don’t disarm responsible people,” she said.

At the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research, Deputy Director Cassandra Crifasi worried local sheriffs would improperly take such resolutions as justification for not enforcing laws.

In Marfa, pushback began. Crowley, who left the room not planning to do anything, asked commissioners on Aug. 7 to repeal the resolution. “I’m pretty Texan,” he said in an interview, “and I understand where they’re coming from, but this is pointless and wrong.”

Bentley wrestled with whether she had erred in supporting it along with her fellow commissioners. She sent a letter to the Sentinel on Aug. 12:

“I don’t feel confident that I did the right thing,” she wrote. “I get why people asked for it. …But perhaps before hastily voting, we should have taken more time to read and research and deeply understand what kind of message we wanted to send.” emily.foxhall@chron.com

“I don’t feel confident that I did the right thing. … Perhaps before hastily voting, we should have taken more time to read and research and deeply understand what kind of message we wanted to send.”

Brenda Bentley, Presidio County commissioner