Census misrepresentation disparages Arab Americans

By Massarah Mikati STAFF WRITER

When Randa Kayyali reached the race and ethnicity portion of the 2010 census, she stared at the form for a while.

Her options were white, Hispanic and/or Latino, black/African American, Asian, Native Hawaiian and American Indian. She didn’t see a category for herself on the survey: Arab American. So she checked “Other.”

Kayyali is among millions of Middle Easterners living in the U.S. — hundreds of thousands in Texas and Houston — who are severely undercounted because they don’t have a precise category to denote their background on census surveys, researchers and advocates say.

Currently, the bureau defines “white” as those of European, Middle Eastern or North African descent. But many people of Middle Eastern and North African origins and descent argue otherwise — saying their background, culture and overall experience in the United States makes it clear that they are not white, nor viewed as white.

The U.S. Census Bureau came close to including a “MENA” category — Middle East and North Africa — in the 2020 census, recommending it as an optimal addition in a 2017 study. But in 2018, the bureau announced it would not include the category at the direction of federal budget officials.

The communities have responded in frustration, fury, and in some cases, lawsuits. Not only are they being rendered invisible, but advocates fear they are losing out on political representation and services for their unique economic, health and educational needs. According to the 2020 census website, the survey results determine the distribution of over $675 billion in federal funding.

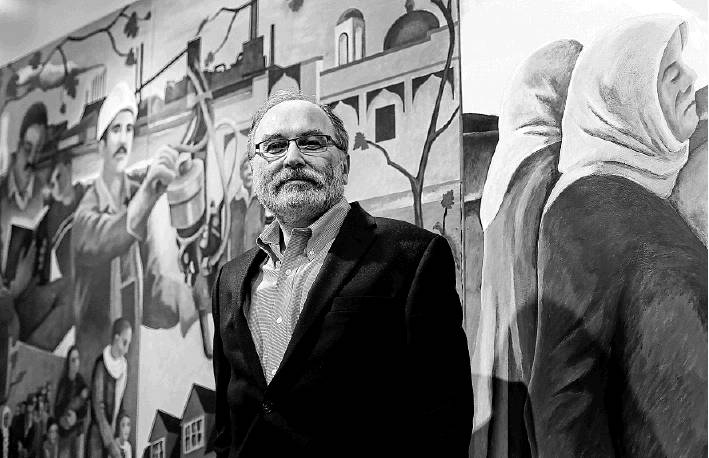

“It’s really unfortunate,” said Hassan Jaber, who is president of the Arab American nonprofit organization, ACCESS, and previously served on the Census Advisory Committee for six years. “All the research for the past six years indicated that if it were available, communities from MENA backgrounds would choose MENA instead of white.”

Marginalized and invisible

A century ago, though, George Shishim had to fight to be classified as white.

Up until 1965, non-white immigrants were not eligible for citizenship in the U.S. That initially included Shishim, a Syrian-Lebanese immigrant who had been classified as Asian, along with a large wave of predominantly Arab Christian immigrants at the time. But Shishim successfully challenged his racial classification in court in Los Angeles in 1909, and Middle Easterners have been considered “white” for census purposes ever since.

“They clearly, like all immigrants who came to this country, understood the racial hierarchies,” said Ussama Makdisi, chair of the Arab Studies department at Rice University.

They also were coming from a very different world than their counterparts who immigrated to the U.S. in the 1960s and later.

In the late 1800s, nation-states hadn’t existed in the Middle East yet — it was still the Ottoman Empire. Colonialism had not hit the region, resulting in a “pan-Arab” movement that spread like wildfire across the Arab world, encouraging the colonized to be proud of their identity. The Palestinian-Israeli conflict had not begun.

And so when the next major wave of Arab immigrants started coming to the U.S. after the 1960s, there was a different dialogue, idea and identification of what it meant to be Arab.

“These people are shaped very powerfully by that context of the Arab world,” Makdisi said. “And that’s why they’re acutely aware of what it means to be Arab in a way very different from the early immigrants.”

By the 1980s, and with the establishment of a myriad of organizations advocating for Middle Easterners, those new immigrants wanted to be taken out of the white category.

The Arab American Institute, a nonprofit organization, has been advocating for the bureau to add aMENA category to the census since the 1990s alongside other groups, to no avail.

Through the last census, the only way Middle Easterners could denote their background was if they were chosen to complete a long-form survey, which included a question about ancestry — leaving major discrepancies in the estimated number of Middle Easterners in the country.

In a footnote on one of their recent reports, the Arab American Institute said the sparsely-dispersed long form surveys cause an undercount of Arabs by a factor of about three.

“Reasons for the undercount include the placement of and limits of the ancestry question (as distinct from race and ethnicity); the effect of the sample methodology on small, unevenly distributed ethnic groups; high levels of out-marriage among the third and fourth generations; distrust/misunderstanding of government surveys among more recent immigrants, resulting in non-response by some; and the exclusion of certain sub-groups from Arabic speaking countries, such as the Somali and Sudanese, from the Arab category,” the footnote reads.

According to the group’s estimates, there are 3.7 million Americans of Arab descent. The census had estimated just 1.9 million. Texas has the fourth-largest Arab American population in the country at over 124,000, according to the Arab American Institute.

A Houston Chronicle analysis of long-form census data found the Middle Eastern population, which includes people from Turkey, Iran and Israel, was over 281,000 in Texas for 2013, and over 98,300 in the Houston metro area. However, the limited data yielded margins of error of 24,400 and over 27,700, respectively — decreasing the data’s reliability.

“There are many segments of our community that don’t recognize themselves on the existing race/ethnicity questions, and this could provide more encouragement for them to participate,” said Helen Samhan, executive director of the Arab American Institute. “It’s extremely important because many local, state and county governments rely on census data to provide services to their immigrant and foreign-speaking populations, and one of the ways those services can be allocated appropriately is if there is official data counts from the U.S. Census.”

According to Jaber, some of the issues unique to the Arab community in the Detroit area — which has the largest Arab population in the country — include higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder, diabetes, smoke addiction and unemployment.

“These are the things that are especially challenging to Arab Americans, but it doesn’t show in the white population as Arabs,” Jaber said. “We could at least understand the needs better and make a better argument for funding.”

‘A tangled scheme of yarn’

Within the Middle Eastern community itself, not everyone agrees on the merits of identifying as white or not. Researchers, academics and community members have observed divides along generational, and even religious, lines.

For instance, Ruth Ann Skaff, a third-generation Lebanese American and member of the Houston-based Arab American Education Foundation, said she noticed that many Lebanese Christians just want to be Lebanese Christian — not Arab, not Middle Eastern, and sometimes not even white.

Part of the reason, Skaff hypothesized, is that being Arab has become a stigma, and is also often conflated with being Muslim.

“I do think that people do not want to be stigmatized, and there is a desire to assimilate among some, which is definitely legitimate,” Skaff said. “And there is the desire to maintain identity, which is also legitimate. It’s a very tangled scheme of yarn, this issue of identity — particularly from the oldest-populated region of the world.”

Kayyali, an independent scholar based in Seattle, found in a recently published study that Christian Arab Americans who were older than 45 and not activists self-identified as white “almost staunchly.” But those younger than 40 identified overwhelmingly as non-white.

“The younger ones are more in tune with a more complex understanding of race,” Kayyali said. “It’s not simply you’re either black or you’re white — there’s been a greater understanding that olive is ‘of color.’”

Matthew Mutammara is a Houstonian born to Iraqi immigrants. But the Rice University student said he and his brother definitely pass as white — they have white skin and brown hair, they don’t speak Arabic and they’re Catholic.

Yet he still hesitates when it comes to checking the box that defines his race and ethnicity on applications and other forms.

“Even though I know I have a lot in common with white kids I grew up with, it feels like you’re giving up a part of your identity to check that box,” he wrote in an email. “My heritage, as distant as it may sometimes feel, is important to me, and I think that a country of immigrants like America should invite us to share those kinds of things.”

Another reason that some Middle Easterners might choose to define themselves as white is not to raise any red flags during a time that being Arab is stereotyped as dangerous, scholars said. Most of the 9/11 attackers were from Saudi Arabia. The U.S. has fought two wars with Iraq and one in Afghanistan since 1990, and Iran has been viewed as an adversary since the hostage crisis of 1980-81.

Yet it is that same anti-Arab, -Muslim and -Middle Eastern rhetoric that was brought about by the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and that some say was inflamed during the Trump administration, which has drastically reduced admissions from Muslim refugees, that has also made a clearer distinction about who is and is not white, scholars say.

“For all sorts of reasons, Arabs have a particularly negative place in the American psyche today,” Makdisi said. “In this day and age, post-9/11, where the ire of American foreign policy is directed towards the Middle East and Muslims, the idea that Arabs are white is ironic.” massarah.mikati@chron.com

“My heritage, as distant as it may sometimes feel, is important to me, and I think that a country of immigrants like America should invite us to share those kinds of things.”

Matthew Mutammara, a Rice University student and Houstonian born to Iraqi immigrants