Surge in migrant crossings hits Big Bend

By John MacCormack STAFF WRITER

PRESIDIO — When almost 100 Central Americans, including many women and children, waded the shallow Rio Grande here recently, Border Patrol agents in the undermanned outpost in far West Texas quickly called for backup from the Marfa and Alpine stations.

Immigrants who were sick or injured were sent to a hospital in Alpine, those needing delousing to the port of entry, single adults to Marfa, and unaccompanied children and adults with children to Van Horn, 135 miles away.

During the labor-intensive processing, the checkpoint on U.S. 67 was temporarily unmanned.

“With that group, we had no warning. They were on chartered buses,” recalled special agent in charge Derek Boyle, who came to Presidio a year ago.

It was among a series of mass arrivals last month, when 18 groups of at least 20 people came across from Ojinaga, Mexico, something never before seen here.

Perhaps it was inevitable that the political and humanitarian crisis on the border would eventually reach the Big Bend, a region long buffered by its remoteness and its harsh terrain. So dear to tourists, but so difficult to patrol.

All told during May, agents in the Border Patrol’s Big Bend sector detained about 1,200 people, roughly 900 of them in Presidio, a rate far higher than normal.

While that was a mere trickle when compared with almost 50,000 people detained in May in the Rio Grande Valley sector and nearly 40,000 in the El Paso sector, for the Big Bend it was extraordinary.

“The unfortunate reality is that the level of increase in apprehensions is not linear, it’s almost exponential. We’re almost doubling as we go from one month to the next,” said Matthew Hudak, who two months ago became the new Big Bend sector chief.

In 2014, only 4,096 people were apprehended in a sprawling sector that encompasses 165,000 square miles and includes Oklahoma. Last year, 8,045 people were detained in the sector.

The sector’s roughly 500 agents cover more than 500 miles of the river border, all but a small fraction of which is rough backcountry. The Presidio station alone is responsible for 113 miles of the Rio Grande.

Given the vastness of his sector, Hudak readily acknowledged the impossibility of having a presence everywhere.

“We have 25 percent of the southern border, but we also have the smallest staffing on the southern border, roughly a third of the next smallest sector. You can do the math and get a good picture,” he said.

Hardship post

Not long ago, most immigrants detained here were Mexicans, single males heading north looking to work.

Now Central Americans fleeing poverty and violence are appearing almost everywhere, wandering around downtown Alpine, entering Big Bend National Park in large groups and turning up in Terlingua at the Brewster County Family Crisis Center, where two stranded Guatemalans recently sought help.

In late February, when three exhausted and dehydrated Salvadorans stood waving for help on a road north of Marfa, a local lawyer picked them up, only to be quickly pulled over by a sheriff’s deputy.

For a while, it appeared that the Good Samaritan impulse by Teresa Todd, 53, the city attorney in Marfa and county attorney of Jeff Davis County, might lead to federal charges. Only recently did her lawyer in Alpine breathe a sigh of relief.

“They’ve missed three grand juries without indicting her, and the material witnesses have been released from marshal’s custody without depositions, so I believe she is free and clear,” Liz Rogers said.

Jose Portillo, the city administrator in Presidio and a former state trooper, is close to some of the Border Patrol agents stationed here, a station that not long ago was officially designated as a hardship post.

Some agents, he said, are feeling overwhelmed by the waves of Central Americans, who pose complex new problems.

“There are some coming across who don’t speak English or Spanish. They speak an Indian dialect. It’s a whole new wrinkle,” he said.

“I have witnessed these Central Americans, and some arrive in very poor health, with obvious lesions on their chest and hands. Most have no idea of what a vaccination is for small pox or polio or measles,” he added.

Since the mass arrivals began, Presidio agents have learned to consult with local and federal officials in Ojinaga to better prepare for them. They check almost daily to learn how many arrive on the public buses coming from Chihuahua City.

Agents now also go regularly to certain upriver spots, where crossing is easier and the Central Americans gather and wait to be picked up.

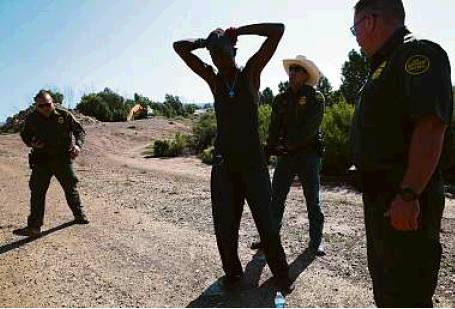

With agents in plain sight one morning, a lanky man in a red shirt was led to the river’s edge by a well-dressed companion, apparently his guide. The tall man quickly swam to the U.S. side and ran to the top of a flood levy, waiting to be arrested.

“I’m from Honduras. I’m here for asylum. They killed my brother. Help me please,” said the man, a 32-year-old whose documents identified him as a Honduran merchant marine.

As he was being searched and questioned by the agents, who requested his name not be published, the shoeless and muddy traveler became emotional, weeping as he denounced both his native country as full of “devils” and the one he had just passed through.

“Mexico treated me bad. I had a month of suffering there. I want to prosper. I want a future that my country can’t give me,” he exclaimed.

Caught on camera

Sheriff Ronny Dodson, now in his fifth term, goes back four generations in Brewster County, which covers more than 6,000 square miles and shares a long wilderness border with Mexico.

He and his nine deputies patrol an area more than three times the size of Delaware but with a population of only 9,400 people.

Dodson, 57, who has two deputies working full time with the Border Patrol, said the partnership is good.

During a nine-hour ride-along over highways and bumpy ranch roads and down hidden canyons used by smugglers, only one other government vehicle was seen, a parked military surveillance truck.

Sometime later, after traveling miles through the backcountry, he stopped below a ridgeline.

“You can see why this would be a great spot. When they top out, they can get cellphone service and they can see the highway,” he said.

Once the illicit travelers reach U.S. 90, he said, they are beyond the checkpoints and essentially home free to reach Interstate 10 and all points beyond.

The sheriff, who has more than 90 hidden cameras on routes used by immigrants and smugglers, said Central Americans are regularly detained and turned over to the Border Patrol.

“We had four yesterday, three the day before below Marathon. It’s every week easily, and sometimes several times a week,” he said.

“We catch them when they come out of the (Big Bend National) park. A while back, the park had three groups of about 50,” he said.

But, he added, seeing them and then catching them are two different things in a region where ranches run to 100,000 acres or more and routes from the river are many.

“I tell everyone we run a pretty nice camera system. We recently saw 68 of them on the cameras. We deployed, Border Patrol, everyone, and just to let you know, we caught six of them,” he said.

Other local travelers, including wild hogs, mountain lions and black bears, also regularly appear on the surveillance cameras.

On the other hand, sometimes all the diligence pays off. Turning off U.S. 90 near Marathon, the sheriff relived a series of memorable busts on a large ranch that welcomes his presence.

“In a 2½-month period, we got almost 7,000 pounds of marijuana and 80 aliens. These guys were dressed like military guys. We got over a million views on our Face-book page. It was back when everyone was talking about the wall,” he said.

As far as a border wall goes, Dodson is emphatic in his opposition, in his county at least.

“They can put a wall all the way to El Paso. I don’t give a hoot. Just don’t put one here in the Big Bend National Park. It’s our tourism,” he said.

Growth industry

Presidio, a long-overlooked, low-income city of 5,000, some 460 miles from San Antonio, appears poised for a growth spurt.

A new railroad bridge to Mexico is nearing completion, replacing one burned down years ago. New vehicle lanes are being added at the international bridge leading to Ojinaga, a city of 40,000 with many social and business links to Presidio.

Natural gas service recently became available to the city, and several new businesses are rumored to be coming to town.

Boyle, the special agent in charge, who chose Presidio as his final career stop with the Border Patrol, expects illegal immigration to be a growth industry here as well.

“Five years ago, you would never have dreamed of getting multiple groups of 50 to 100 here. Five years from now, this will be like all the other sectors. We’ll get the same traffic you get at the other, larger ports of entry,” he predicted. jmaccormack@express-news.net