Vendor linked to bribery scandal returns

Former public works director again seeks engineering contracts

By Zach Despart and Mike Morris STAFF WRITERS

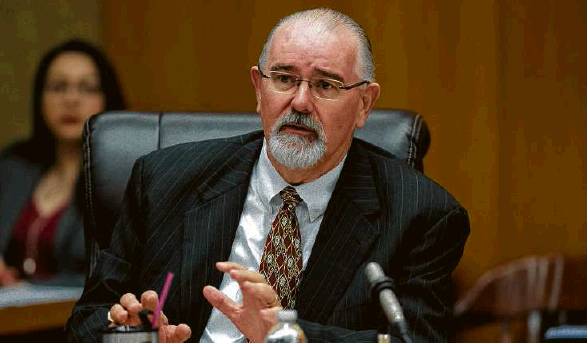

Two men in business attire sat across from Harris County Engineer John Blount in the downtown administration building earlier this year, making the routine visit Blount asks of all engineers wishing to be added to the county’s list of approved vendors.

These attendees already were well known, however, not only to Blount, but to nearly every political player in Houston.

One was Karun Sreerama, an engineer and prolific political donor who resigned as Houston Public Works director two years ago after payments he made to a Houston Community College trustee who pleaded guilty to bribery charges became public. The other was Jerry Eversole, who had a corner office on the building’s top floor as a county commissioner for nearly two decades until his resignation as part of a 2011 plea deal in a federal corruption case.

The pair were in Blount’s office Feb. 7 seeking county work on behalf of DHAR Engineering & Consulting, Sreerama’s new firm. Six weeks later, Precinct 4 Commissioner Jack Cagle asked Blount to place the firm on the Commissioners Court agenda for a road project.

The court approved the engineering department’s request to negotiate the contract on March

26. Sreerama donated $5,000 to Cagle’s campaign two days later. Final approval of the contract would require a second vote.

Less than two years after Sreerama took a relative hiatus from public life in the wake of the HCC bribery scandal, the politically connected engineer has been welcomed back by city and county officials as a contractor, business partner or campaign contributor. In the past 14 months, Sreerama has become a certified city and county vendor, partnered with a city councilman to whom he also lent money, and donated to at least two county commissioners and the Harris County Democratic Party.

A Dallas-based engineering firm named EJES also has asked the Harris County Flood Control District for a meeting, and said Sreerama would attend. The county has just begun spending from a $2.5 billion bond issue on flood mitigation projects, the largest investment in its history.

Sreerama’s renewed courtship of local governments surprised some observers because of the publicity surrounding his previous relationship as a vendor to the Houston Community College system, during which federal court records revealed he made $77,143 in payments to Chris Oliver, an HCC trustee.

Those payments were made between December 2010 and August 2013 while Sreerama also ran an engineering company doing business with the school. The FBI confronted Sreerama about the payments in 2015, after which court record show he agreed to pay Oliver another $12,000, forming the basis for the bribery charge to which Oliver pleaded guilty; he now is serving a six-year sentence.

Sreerama, who was not charged with a crime and was labeled a “victim” in court documents, has called it “nonsense” that he was depicted as someone who paid bribes, saying his first two payments to Oliver were loans the trustee never repaid, and the third took the form of an exorbitant fee Oliver charged after his company cleaned the parking lot at Sreerama’s business.

This explanation proved insufficient to stop Sreerama from losing his post atop Houston’s sprawling Public Works department just four months after Mayor Sylvester Turner had appointed him, or to prevent political observers from raising ethical questions as he returns to the fold now, said University of Houston political science professor Brandon Rottinghaus.

“The ongoing relationship between Sreerama and local government is stunning,” Rottinghaus said. “These relationships show that even the disinfectant of sunlight cannot slow the cozy, powerful relationships between political insiders and government contracts.”

Whether Sreerama’s return to public life should concern Harris County residents likely depends on how credible they find the engineer’s account of the Oliver payments. The elected officials willing to speak about their work with Sreerama say they believe his version, though they acknowledge some may doubt its veracity.

Cagle described Sreerama as an exceptional engineer who made the right choice by cooperating with the FBI in the Oliver case.

“If I didn’t believe him …I would not have given him this job,” Cagle said. He added, “If he doesn’t perform like I’m expecting him to, then no, it would not have been worth the headache, and no, he won’t get any more work.”

In a brief conversation at his Fifth Ward office, Sreerama said Monday that he was heading out of town and unavailable for an interview. In a response to emailed questions, Sreerama said he has a good reputation as an engineer. After pursuing other ventures during his hiatus, including running an online cellphone accessory store and Tex-Mex restaurant in Houston’s Museum District, he wished to return to his profession.

“I would like to get back to engineering projects as that is what I enjoy doing and my best path to providing for my family,” Sreerama wrote.

Eversole declined to discuss his work with Sreerama.

Back in the game

Sreerama’s close ties to elected officials helped cost him his job atop Houston Public Works, but he has not avoided these relationships in returning to public life.

DHAR, the firm now in line for county work, was formed by Houston City Councilman Jerry Davis in December 2017, records show. Davis, who is term-limited and will leave office at the end of the year, said he proposed starting the company to Sreerama, envisioning the firm tackling a range of public- and private-sector jobs.

Davis said he became close to Sreerama during his time on the council, dining together and attending celebrations for each other’s children, and said he accepts Sreerama’s description of his payments to Oliver, which he said were “in horribly bad judgment — he’s that much of a nice guy.”

In June 2018, Sreerama filed paperwork registering DHAR in his name and replacing Davis’ name with his own as the firm’s manager. Davis said he agreed to sell the company to Sreerama in part because Davis said Sreerama “begged” him not to continue with the company for fear the councilman’s reputation would be tarnished by association.

“Since Day One he said, ‘Are you sure you want to have my baggage?’ And I was like, you know, that’s my friend, I don’t see the baggage,” Davis said. He eventually capitulated, however. “I said, all right, let’s not do the company because there are people who are not going to believe you. We’re going to have doubters. That’s just part of life.”

Davis said he sold DHAR to Sreerama for a modest fee intended to cover the time and expense of filing the paperwork to form it; the firm then had no office, no employees and no projects.

Davis said he and Sreerama still are pursuing a business venture related to housing, however.

Last Sept. 12, Davis and his wife put three rental properties they own on Stuart Street in the Third Ward up as collateral to secure a $153,481 loan from K&S Interests, a company Sreerama formed in 2010. The next month, Davis borrowed another $115,000 from K&S Interests to buy a fourth property on Stuart.

Davis said he sought private financing from Sreerama rather than going to a bank in part because he was nearing a 10-loan cap Fannie Mae places on investors, and in part because he and Sreerama were interested in housing-related investments. Sreerama said he is working through a housing company he formed to build several modest homes, though he said no public official is involved; his firm got initial permits to build two homes in Fifth Ward, but the lots remain vacant.

Davis said the transactions are market-rate loans on which he makes regular payments, saying, “I have a financial interest in it — it’s not like it’s one-sided, like with the other conversations about elected officials. This is a business.”

Both men stressed that Sreerama has agreed not to seek city work while Davis is on the council to avoid any perceived conflicts of interest.

Though Sreerama registered DHAR as a minority vendor with the city, Davis said that is because the city’s Office of Business Opportunity is the agency that certifies small-, minority-and women-owned firms for 10 government agencies in the region. City officials could find no evidence the firm has received city contracts, gotten any city payments, or bid on any city work.

Davis said he was “disappointed” Sreerama’s return to public life would be greeted with scrutiny.

“It just seems like this man can’t get a break,” he said. “Can he do business and put food on the table for his family?”

Longtime player

Sreerama, a native of Hyderabad, India, moved to Houston in 1988. Between the two countries, he has earned four postgraduate degrees, including a master’s in business administration and a doctorate in engineering.

He worked as an engineer in Houston for 16 years before purchasing ESPA Corp., an engineering firm founded by the late county commissioner El Franco Lee, in 2005. Sreerama sold the company in 2012, but stayed on as president until mid-2014.

During part of Sreerama’s tenure, ESPA got $1 million in county work from three different commissioners and at least $12 million as a contractor or subcontractor for the city or city agencies.

Sreerama also has been a prolific political donor. From 2009 through 2018, he contributed $313,000 to city, county, state and federal candidates or committees. In 2015, he and family members contributed $20,500 to Sylvester Turner’s successful mayoral campaign.

Sreerama contributed less in 2017, the year of his brief tenure in Houston city government, than any year in the past decade. His giving, however, has picked up since.

Sreerama was at a Harris County Democratic Party fundraiser May 24 featuring former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, according to two people who attended. Party chairwoman Lillie Schecter said staff had yet to tally Sreerama’s contribution.

Cagle is the only member of the Commissioners Court to have received acontribution from Sreerama in 2019. Sreerama contributed $1,000 to Precinct 1 Commissioner Rodney Ellis in 2018; his precinct also has one current connection to the engineer.

Ellis’ office in March selected Dallas-based firm EJES as a subcontractor on a flood control district project. An EJES manager on May 2 asked the flood control district for a meeting to discuss future projects, and said he would bring Sreerama.

The district recently has begun awarding contracts for its $2.5 billion bond program, which quintupled its capital budget almost overnight. Flood control district leaders did not respond to the EJES email and have not had any communication with the firm since, a spokesman said.

Sreerama said he has no role with EJES and could not explain why the firm would include his name in an email. EJES Gulf Regional Manager Kamal Rasheed said the firm has no agreement with Sreerama, but has discussed using DHAR as a consultant on future projects.

Ellis, in a statement, said Precinct 1 selects from a list of qualified firms compiled by the flood control district, with a preference for women- and minority-owned businesses. He did not answer questions about Sreerama.

A ‘raw deal’

Cagle said he was eager to work with Sreerama after the engineer resigned as Houston’s public works director in July 2017. The commissioner commended Sreerama for helping FBI agents make a case against Oliver, and said he got a “raw deal” by being forced from his job.

When Sreerama registered DHAR as a county vendor in February, Cagle asked Blount, the county engineer, to hire the firm for a routine project improving a 1.7-mile stretch of roadway in northwest Harris County.

The engineer’s office typically recommends a list of suitable firms from which a commissioner can choose for a project in his precinct. Cagle, Blount said, is the only commissioner who does not typically seek the advice of his office before selecting engineers.

Cagle said he was unaware Sreerama had cut a $5,000 check to his campaign after the court vote in March until a Chronicle inquiry prompted him to ask an employee on June 1. Like the three other commissioners, Cagle relies heavily on county vendors for campaign contributions — 82 percent of his donations last year came from this source — and, like his colleagues, he rejected any suggestion of a relationship between donations and contracts.

“I didn’t give him a job to get a contribution,” Cagle said of Sreerama.

Commissioners Court must approve each contract, though members long have refrained from meddling in each other’s projects, which good government critics say effectively makes precincts fiefdoms where commissioners individually control tens of millions of dollars in annual infrastructure spending.

County Judge Lina Hidalgo made ethics a pillar of her campaign last year and in January announced she would refuse contributions from vendors. She said she has yet to decide whether to support the DHAR contract.

Rottinghaus, the UH political scientist, said the proposal is a prime opportunity for Hidalgo to show she is serious about changing the way Harris County does business.

“It’s one thing to decide not to take money from specific contractors and engineers,” Rottinghaus said. “It’s another to decry the shady deals right at the doorstep of county government.” zach.despart@chron.com mike.morris@chron.com